Minsk: A fusion of mobility futures

Andrey Vozyanov

Probably one needs a background of living in or studying the former USSR space to be strongly surprised once after entering the city of Minsk, capital of Belarus with 2 million inhabitants. The astonishing effect emerges from the visual contrast of reality to the wild totalitarianism`s images by which Belarus is surrounded. The specific narrative of „last European dictatorship” is another story, but Minsk`s first look in April 2015 was definitely more European than you would find in Russian or Ukrainian cities-„millionairs”. City is full of big capacity buses, tramways and trolleybuses, while 100 % fleet is of Belarusian production. Minsk`s subway system is the one fastest growing in ex-USSR (after Moscow). Marshrutki – privately-operated small-capacity buses/vans servicing the fixed lines (often overlapping with municipal ones) – are only marginally present in Minsk. The interesting thing is that some are still there – which proves they are not prohibited by the state; municipal transit company actually manages to do what almost none of post-socialist cities has done – that is to retain own clients-passengers without administrative expulsion of marshrutka from the market.

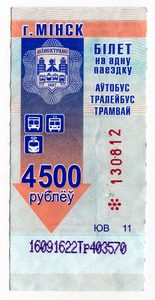

Ticket prices can cause cognitive resonance for “Westerners” until they realize that 5000/5500 Belarusian rubles are not more than 25 euro cents. There are no vending machines, so you have to buy tickets in a kiosk at the stop (or from the driver, with a 10 % overprice). The drivers sometimes do not have rest money, and kiosks are not working late in the evening, thus a few tickets is a usual thing to have in pocket.

Photo by Arseny Loysha

Trolleybus champion

Minsk has world`s second largest trolleybus network, with over 490 km of wiring, thousand of vehicles and about 60 lines. Trolleybuses are painted green, and can be seen basically on every large street (except the main one, Praspiekt Niezaliezhnasci, where trolleybus overhead wiring was considered visually inesthethical by authorities…). They are quietly passing by with inimitable sound of electric engine and the trolley-pools sliding under the wires. Remarcably, most of them are articulated low-floor fleet, and the rest is being replaced quite actively. More lines were under or planned for construction until recently, when authorities declared that electric buses will be prioritized. The decision is met with a scepticism by many, since the new technology will require a (not short) period of tries and failures instead of maintaining a well-tried trolleybus infrastructure. Mind that Belarus widely exports its trolleybuses to Russia, Ukraine, Moldova, Romania, Serbia and some other countries.

Photo by user IKS, transphoto.ru

Belarusian language and mobility

The public transport in Minsk is also particular for it is the only space where people daily hear Belarusian language, very limitedly spoken in this predominantly Russian-speaking society. The stops and information are announced in Belarusian, as well as security recommendations (like „beware of the pickpockets”). Earlier, all these infos were announced alternately in Russian and Belarusian, but more recently were all translated into the title language, which produces a modest effect: one can ocassionally hear how people insert phrases in Belarusian into phone conversation (e.g. наступный прыпынак and not the Russian следующая остановка for ”the next stop”). The other trick is that month tickets have the names of the months written in Belarusian (which matters, cause unlike in Russian with its Latin-derived months` names similar to English, German, French etc., Belarusian has preserved typical Slavic names related to the natural occurrences – like snow for снежень (February)). Also, you have all the street navigation in Belarusian (gradually more frequently doubled in English) and a petrol stations chain which was one of the first private enterprises to prioritize Belarusian as a language of communication with the clients.

Bicycling

Minsk boasts an impressive amount of bicycle lanes – again, significantly larger than in any comparable city across former Soviet republics. Let`s admit, it is only 300 km of the long promised 500 km which are often just painted over the pedestrian sidewalk dividing the latter by two. City benefits from wide prospects, inherited from post/war Soviet urban planning – normally you can, as minimum, draw the bicycle lane on a wide pedestrian space. Still, even such visualization serves as a kind of promotion for bicycle use, which locals evidence to have drastically increased in last five years, covering population groups of different age. There is also a gorgeous bicycle lane along the recreation areas, very popular in the warmer half of the year. Also, with efforts of activists, the funding was allocated to make substantial number (hundreds) of kurbs flush in 2015.

Photo by Andrei Karpeka

Night frontier

Minsk has a kind of late evening and night infrastructure that would seem quite unusual for European capitals. Most lines function approximately until half past midnight – which is by no means motivated by comfort of clubbing youngsters or relaxed tourists. Night transport connects industrial zones with sleeping areas, taking second shift workers home and night shift workers to the plant. It is frankly lacking on Kastryčnickaja street, a gentrified area with bars, clubs and art spaces at the margins of city centre, still preserving the „true industrial” fleur of Soviet times (as several plants are still operating there). Similarly story is the Upper Town, one more area to hang out at, which is announced to become a pedestrian zone since May 2016, but is unaccesible by public transport from 0:30 to 5:30 am. Strangely, the surface transport stops operating earlier than the subway in the evening – which creates tricky geographical hierarchies for locals. Although on the surface there are real-time arrival information displays which ”tame” the waiting and a mobile app indicated the planned departures, missing the last subway train which leaves every end station at 1.02 am seems to be more common memory figure.

Becoming a car society?

One more provoking detail in mobilities landscape of Balarusian capital is the outstandingly (in negative sense of the adverb) small tramway network – up to dozen times smaller than in other 2-million European capitals (Warsaw, Prague, Bucharest or Budapest). While supporting here and there public transportation on the shared roads (and scarcely with separarte bus lanes), Minsk authorities perpetually postpone the promised tramway network extension. Instead, the highways and interchanges are growing in number, and the backyards are overcrowded by parked cars (which is not seen from the wide prospects). At the risk of motorization upsurge, Minsk demonstrates a vibrant in-betweenness in relation to both sustainable mobility paradigmal efforts of the °West° and to suffocative car anarchy of developing countries.

Photo by Andrei Karpeka

Special thanks for photos and precisions to Andrei Karpeka, Minsk Urban Platform