Roads and Travel in Tanzania: A Reflection on History & Current Trends

By Katie V. Streit

Katie Valliere Streit is an independent scholar based in Dayton, Ohio. Streit obtained a PhD in History from the University of Houston. Her research focuses on the history of automobility and state development in southern Tanzania during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Historians spend countless hours in libraries and archives with backs bent, eyes strained, and fingers stained with ink. We diligently strive to read any and all secondary and primary sources that could help answer the questions driving our work. Many historians of technology, however, have unique opportunities to set aside the manuscripts and physically engage with the instruments, mechanism, and networks they are researching. New and more nuanced insights can arise when historians operate telephones or repeating rifles, observe hydroelectric dams or blacksmiths forging tools, manipulate plastics or textiles, ride in trains or aircraft, and so forth. Travelling over 3,600 km on public transportation in Tanzania altered my perception of the ways in which infrastructure deficiencies impacted lives and livelihoods in the nation’s southern region for the past century.

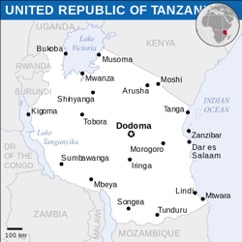

Figure 1. Map of Tanzania created by the United Nations Officer for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). Source: United Nations Officer for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), “United Republic of Tanzania.”

My investigation into the history of road transportation in southern Tanzania began with a seemingly simple two-part question, “Why was there a lack of all-weather roads in southern Tanzania, and how did their absence hamper the region’s economic development?” My predecessors had addressed the latter half of the question. They concluded that the failure of the colonial (1880s-1961) and post-colonial states to construct adequate transportation infrastructure in the south aggravated the region’s real and perceived impoverishment and isolation throughout the twentieth century.[i] I reached a similar conclusion after two years of archival research in Tanzania and England. Colonial authorities and private investors were eager to improve infrastructure in southern Tanzania (then German East Africa) in the 1890s in order to better exploit natural resources and create a lucrative, cash crop producing landscape. The physical destruction and social unrest caused by the Maji Maji rebellion (1905-1907) and First World War thwarted colonial “development” schemes in the south. The motorable roads haphazardly constructed by Allied forces to facilitate troop and supply movements during the war quickly deteriorated in the face of neglect and adverse climatic conditions. The abandoned and decrepit roads became a powerful symbol of Southern Tanzania’s isolation and impoverishment in the aftermath of the war, as well as a justification for the colonial state’s reluctance to invest in the seemingly unprofitable periphery.

Throughout the remainder of the twentieth century, government officials stationed in the south repeatedly petitioned the central state to allocate more funds and manpower to improve the region’s failing infrastructure. They recounted tales of nearly careening over ravines and disassembling their vehicles in order to wade them through flood waters as evidence that road improvements were needed in order to improve administrative efficiency and encourage economic progress.[ii] Both the British colonial state and Tanzanian national government, however, invested their limited resources in more prosperous regions accessible by railway networks. At the turn of the twenty-first century, newspaper articles and historians continued to lament the deplorable road conditions. Stranded passengers purchased food from local communities and slept onboard the broken-down buses out of fear of potential lion attacks as they waited indefinite periods for a replacement vehicle to arrive. These stories persuaded me that the history of road transportation in southern Tanzania was innately pessimistic. The dilapidated roads served as a powerful symbol of the region’s isolation and poverty. They helped to justify government neglect and propagate stereotypes that the region was incapable of “development.”

In 2015, I finally travelled to the south in order to collect oral histories from former drivers and mechanics operating in the region from the 1940s to the 1970s. My experiences travelling in southern Tanzania were as varied as the passenger vehicles I boarded, including motor cycles (piki piki or boda boda), auto rickshaws (bajaj), mini-buses (dala dala), and major bus liners. I was shocked by the ease of my journeys south from Dar es Salaam to Lindi (454 km) and northeast from Songea to Dar es Salaam (934 km). After reading numerous accounts of passengers being stuck for days trying to cross the Rufiji River toward Lindi and the perils of travelling through the Southern Highlands out west, I was unprepared for the comfort of the “luxury” buses’ recliner seats, air-conditioning, complimentary food, and in-service movie entertainment. As the buses speed along tarmac roads, I wondered whether southern Tanzania had entered a new era of improved interconnection with the rest of the nation, which in turn facilitated economic opportunity and prosperity for the regional populace.

I could not reconcile this narrative with my experiences travelling in the region’s interior. The 232 km journey across the Makonde Plateau from Masasi to Mtwara (via Newala) took ten grueling hours. The mini-bus was lucky to exceed 20 mph on the back-breaking dirt road. Chicken coops were shoved in the trunk, mattresses strapped to the roof, and passengers squeezed aboard like sardines in the overfilled aisles. If the villagers did not board our bus, they would have to wait until the following day. When I safely arrived in Mtwara, I was certain that I had experienced the worst main road in the south. The ease of travelling along tarmacked roads from Mtwara to Lindi and Lindi to Masasi seemed to confirm my assumption. It turned out that I was mistaken.

Figure 2. Bus from Masasi to Mtwara via the Makonde Plateau. Picture taken by author, 2015.

I ended my field research by travelling west along the main road from Masasi to Songea (460 km) – a road that was the focus of my dissertation. The Tanzanian government had recently commissioned Chinese contractors to oversee construction of a new all-weather, bitumen standard road to Songea – a feat that had not been accomplished in over hundred years. Once again, I found myself boarding a mini-bus before dawn; shoving my bag under my feet and sandwiching my knees into the seat in front of me. Within thirty minutes of departing, the mini-bus diverted from the main road onto an extremely bumpy frontage road. To my astonishment, we remained on the dirt road for the next 15 ½ hours when we reached the outskirts of Songea. Although the driver skillfully dodged the worst potholes and bumps, the passengers uncontrollably bounced about and collided into one another. The windows remained open to combat the oppressive heat. As a consequence, our ears (and my sanity) suffered from an incessant rattling, while our belongings, hair, and skin became saturated in dust and grim that construction trucks kicked up as they barreled past.

My disbelief at the road conditions turned to a silent road rage amid the constant pounding. I finally understood the frustration locals expressed at the government’s inability to construct tarmacked roads. How could anyone access outside markets and conduct profitable businesses under such conditions? If the major east-west road was in such a terrible state, how much worse must the conditions be for hundreds of smaller district and village roads scattered across the south? It was no wonder that activists in the south used the roads as proof of their second-class citizenship.

Figures 3. Construction progress on Masasi-Songea Road (outside Masasi). Picture taken by author, 2015.

Gradually my anger subsided into a deep appreciation for local agency and innovation. I respected the fortitude of countless drivers navigating horrendous roads for the benefit of themselves and their communities. I reflected upon the technological knowledge of drivers and mechanics forced to find innovative ways of repairing vehicles in transit and/or when replacement parts were scarce. I also contemplated the initiative and innovation local communities demonstrated for over a century in the face of inadequate infrastructure. Whether launching beer pots full of cargo across the Mbwemkuru River or transporting motor vehicles half-mile across the Rufiji River aboard a ferry consisting of four bound canoes topped with a wood platform, southern Tanzanians found creative ways to remain mobile.[iii] I gained new respect for the passengers (many of whom stood for hours in the aisle) as they repeatedly endured this and similarly punishing journeys in order to make a living and visit loved ones. I also witnessed the multitude of livelihoods that individuals carved out on and along the road (drivers and mechanics, itinerate traders, precious gem dealers, petrol station owners and operators, teenagers hawking food at bus stops, and so forth). My oral history interviews and conversations with fellow passengers confirmed that individuals throughout southern Tanzaniautilized automobiles as tools to create dynamic, interregional, socioeconomic networks.

While bumping along the Masasi-Songea road, I ultimately encountered parallel narratives of road transportation in southern Tanzania – one of a region’s peripheralization and impoverishment, and the other of local initiative, innovation, and opportunity. My experiences travelling in the south did not undermine my archival research, but rather enriched my research and enabled me to adopt a more nuanced perspective of the past and present realities impacting a dynamic people struggling to improve their lives in an impoverished region of Tanzania. Furthermore, my research challenged the assumption that individuals residing in impoverished regions and nations depend upon technological transfer to experience technological advancements that can improve their livelihoods. I found that southern Tanzanians not only appropriated and adapted imported technologies to fit their needs and desires, but they developed unique methods and systems of constructing, maintaining, improving, and transforming mobility technologies and infrastructures so as to better pursue opportunities locally, regionally, and internationally.

—

[i] Felicitas Becker, “A social history of Southeast Tanzania, ca 1890-1950” (PhD diss., Cambridge University, 2002), 154-55; Chau P. Johnsen Kelly, “A Tale of Two Cities, Mikindani and Mtwara: Consuming Development in Southeastern Tanganyika, 1910-1960” (PhD diss., University of California Davis, 2010); Priya Lal, African Socialism in Postcolonial Tanzania: Between the Village and the World (Cambridge University Press, 2015); Pekka Seppällä, “Introduction,” in The Making of a Periphery: Economic Development and Cultural Encounters in Southern Tanzania, eds. Pekka Seppällä and Bertha Koda (Uppsala, Sweden: Narodiska Afrikainstitutet, 1998), 7-37; Husseina Dinani, “En-gendering the Postcolony: Women, Citizenship and Development in Tanzania, 1945-1985,” (PhD diss., Emory University, 2013); and Matteo Rizzo, “The Groundnut Scheme Revisited: Colonial Disaster and African Accumulation in Nachingwea District, Southeastern Tanzania, 1946-67,” (PhD diss., School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 2004).

[ii] BLCAS MSS. Afr. s. 1738 (27), Lumley, “Forgotten Mandate”; and BLCAS MSS Afr. s. 609, Harry Churchill Baxter, “River Crossing.”

[iii] BNA FCO 141/17730, Tanganyika: Southern Province: Provincial Commissioner’s Monthly Newsletter 1944-1955, T.O. Pike to Chief Secretary, April 10, 1948; and BNA CO 822/139/1, “‘Well, That’s The Biggest Obstacle Crossed’: Major Haulage Transport and Some Snags,” extract from Tanganyika Standard, October 1, 1949.