The Labor of Transport of the “Messengers of the Nations” of the University of Paris in the Fifteenth Century

Martina Hacke, University of Düsseldorf

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- The labor of transport of the messengers of the nations in the sources

- The messengers and their labor of transport

- The hazards of the labor of transport

- Compensation for transport services through privileges

- Attempts to reduce the number of messengers

- The founding of the fraternity of the messengers of the French nation

- The importance of the transport services of the messengers of the nations

- Sources

In the Middle Ages there was no postal service in the modern sense of one that was public and available to all. Instead, private persons were responsible for their own transport operations. Major institutions such as the monarchy or the church, and also merchant associations such as in the Hanseatic League, had organized transport services available. These were not purely public, and not available to private persons, because only the members of the relevant institutions were permitted to use them.

The universities also had need of transport services. Of course one immediately thinks of books for the course of study, but also stone was required for the construction of new university buildings. Overall, medieval universities used many different types of people for transport, depending on the goods, who was ordering, and who was financing. The sources are not always sufficient to research these various forms of transport. However, they are adequate in the case of one university messenger institution, namely the messengers of the nations of the University of Paris. They appear for the first time after the middle of the fourteenth century, or more than a century after the founding of this university, which together with Bologna was, the prototype of the medieval university.

In medieval university sources, a messenger was normally referred to as a nuncius, the middle Latin form of the ancient nuntius. This person was an office holder of one of the four nations of the University of Paris, namely the French, Norman, Picard and English-German nations, which together formed the Arts faculty. Within these nations, which were constituted in the middle of the thirteenth century, the members of the Faculty of Arts organized themselves on the basis of their geographical origin. In contrast, the messengers of nations did not necessarily hold any biographical connections concerning their origins to the nation in which they held their office. They acquired their office by offering their services to a nation of their choice, after which they were appointed to the office through a special procedure and then admitted by members of the nation.

The messengers of the nations carried out transport operations for the private needs of the students and teachers. Tasks of this type could also be handled by free messengers who were hired by members of the university for individual commissions and paid privately. However, in contrast to messengers of nations, it is much more difficult to find references to these free messengers in the university sources. It should also be noted that messengers for the nations and free messengers, who handled transport for private needs of the masters and scholars, were distinguished from another type of messenger, namely, those who were active on the official commission of university institutions, hence of the nations, the faculties, the colleges and the university itself. They were also made use of for single commissions, such as the transporting of letters, but the relevant university institution took care of the relevant financing. Overall, all the types of messengers described here can be delineated with respect to the emissaries who handled negotiations in their capacity as representatives of the university institutions. Such a person was ever more frequently also called ambassiator from the beginning of the fifteenth century, but in the sources of the University of Paris the most frequent term for him was likewise nuncius. The spectrum of the word nuntius ranged from someone who was in effect no more than a courier up to an emissary with full authority to negotiate. An emissary could also take on the function of a messenger, but not vice versa. Only a close analysis of the textual context clarifies whether a nuntius was a simple courier or an envoy. Messengers of nations were officers of their nations. But they were not responsible for the official transport needs of the nation. Instead they were responsible for the private needs of teachers and students.

The labor of transport of the messengers of the nations in the sources

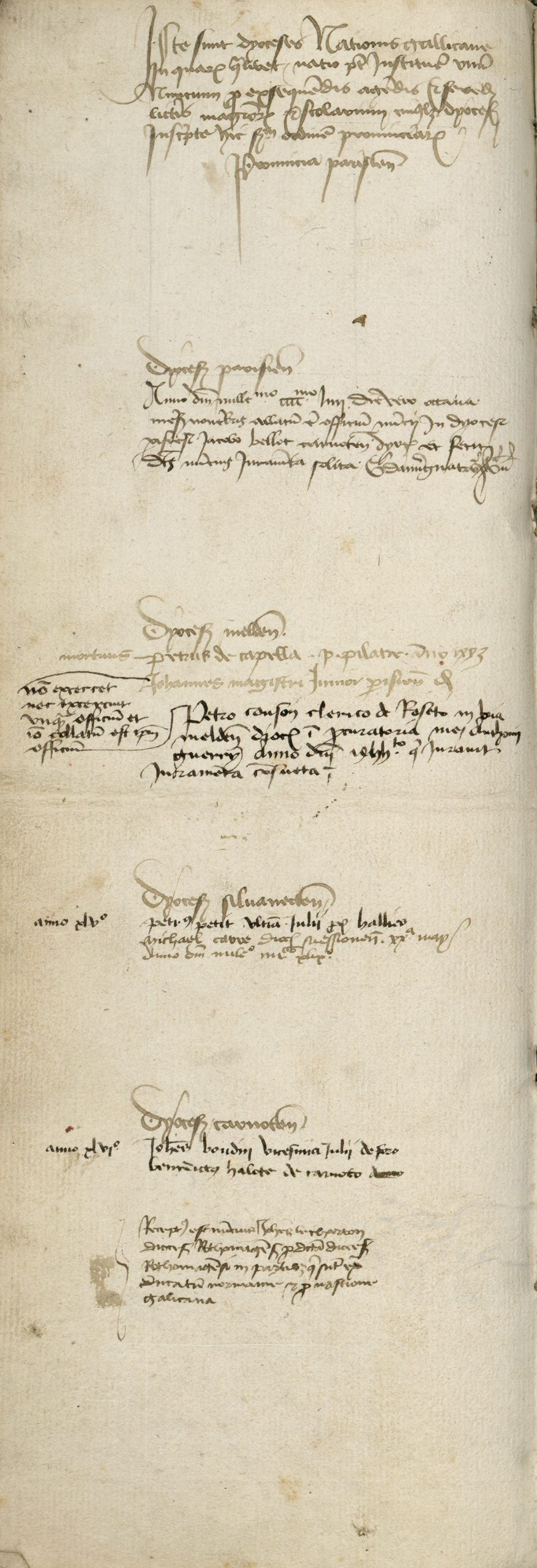

The documents that report on the work of the messengers include official deeds such as royal privileges, municipal records and the files of law courts. The leading sources from the university are the Libri procuratorum, the books of the procurators, who were the leaders of the nations. They contain the minutes of university gatherings and sometimes lists of messengers as well. The “second list” of messengers of the French nation, the beginning of which is shown here, contains eighty-five entries, mainly from the years 1445-1456. It shows the administrative work that the nation performed concerning the labor of transport of its messengers. Due to the fact that the members of a nation were split up on the basis of their home dioceses, a messenger was responsible for members from the relevant diocese. Thus in 1454 Jacobus Bellot took up the office of messenger for the students and teachers of the diocese of Paris.

1445 Sept. 16. “These are the dioceses of the French nation for which a nation can employ a messenger to carry out business transactions and to bring letters to the students and teachers of any diocese […]”

(Iste sunt Dyoceses Nationis Gallicane in quarum qua libet nacio potest institue re unum nuncium pro exsequendis agendis et ferendis litteris magistrorum et scolarium cujuslibet dyocesis […]).

1454 Nov. 8. “Jacobus Bellot from the diocese of Chartres has been assigned the office of the messenger in the diocese of Paris, and said messenger has sworn the customary oath. [Signed by the procurator] G. Dauvergnat.”

([…] collatum est officium nuncii in dyocesi Parisiensi Jacobo Bellot, Carnotensis dyocesis, et fecit dictus nuncius juramenta solita. G. Dauvergnat).

The messengers and their labor of transport

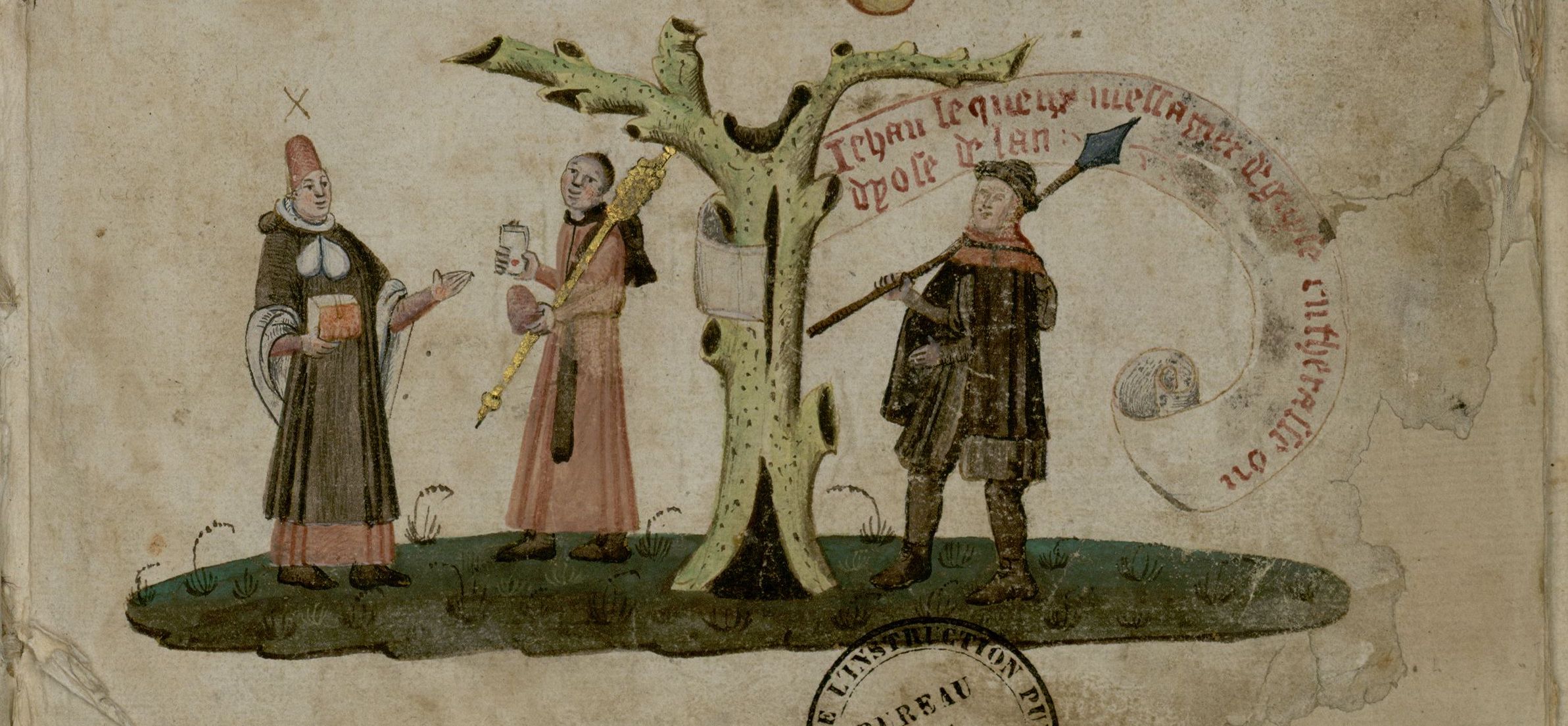

The messengers were officials and servants of their respective nations. The messenger is on the right in this miniature of the Picard nation from 1476. There is a banner above him with the words: Jehan Le Queux, messagier de guyse en therasse, ou dyo[cè]se de Lan. He was the messenger for Guise en Thiérache in the diocese of Laon in northern France. This means that he undertook messenger services for those teachers and students who came from the town of Guise.

The illustration shows the messenger in dark travel garments with his coat, cap and boots. He is carrying a spear over his right shoulder, this being his means of defense. On the left, the procurator holds a package in his hand, and to the right of him is a servant with a sealed letter. Either the messenger has just handed over the two objects, or he is about to receive them.

It is not possible to tell today if the illustration reflects the reality. We know, above all from the Libri procuratorum, that the messengers frequently carried money in addition to letters and packages. Many students were young and needed funds to live and to study, and at that time the banking system was not as prominent in Paris as it was in Italy. Money and objects such as packages with clothes, towels, books and parchment, and medicine and wine, and also news came from the families of the students, primarily the parents.

The length of the journey depended on the distances and the terrain. Johannes Castinerii, messenger for the French nation, was responsible for the diocese of Nevers, which is around two hundred and sixteen kilometers (as the crow flies) to the south of the capital. On the other hand, Gaufridus de Marnef, messenger of the German nation and from 1489 to 1492 nuntius for the diocese of Turku (Åbo) in Finland, which belonged to Sweden at that time, had to cover eighteen hundred kilometers (as the crow flies). The messengers usually traveled on foot, but some also on horseback.

The hazards of the labor of transport

Travel was dangerous in the Middle Ages. We learn of the robbing of a messenger of the German nation for 1491:

“Secondly, a certain messenger of the Picard nation hereby supplicated:

While he was on the way to Paris with some teachers and students they were held up and robbed of their goods and money in Thérouanne, so that they were forced to come to Paris without any money, which is major damage to the university and a wrong.

The nation has therefore decided that the wrong is to be made good as common costs from the university funds and to do this, the nation has decided to give any type of help.”

(Secundo supplicuit quidam nuntius nationis Piccardie qui, cum Parisium veniret cum quibusdam magistris et scolasticis, in civitatem Morinensem omnes captivi ducti sunt et suis rebus et pecuniis spoliati, Parisium sine pecuniis sunt coacti accedere, quod quidem est in magnum prejudicium Universitatis et injuriam. Placuit nationi ut communibus expensis ex erario Universitatis prosequatur talis injuria et ad hoc faciendum placuit omni modam dare assistentiam.)

(Excerpt from the “Liber procuratorum” of the German nation from 1491, Nov. 21).

Hence the messenger of the Picard nation traveled with a group, which was a matter of course at that time for safety reasons. In this case his companions were teachers and students of the university itself. In November the group was held up and robbed in Thérouanne in northern France, around two hundred kilometers from Paris.

The fact that the messenger could provide witnesses out if his own circles undoubtedly played a role in his plea for material compensation. For who was liable in such a case? As the quotation shows, the nation wanted the university to reimburse the messenger from its own funds. But the higher faculties did not agree to this, so that ultimately the treasurer of the Arts faculty started up a collection for the messenger, in other words, a voluntary donation.

Compensation for transport services through privileges

The messengers did not get any money per se from the university or nation for their transport services. They probably received money from the persons for whom they performed the transport services, but no proof of this can be found in the university sources. Instead, they were granted privileges. These privileges came from the pope and the king and they were due to the messengers because they were officers of the nations and hence officers of the university. The most important of these was the privilege of clergy, which was given by King Philipp Augustus in 1200 to the Parisian masters and scholars and their servants. Most of the privileges of the messengers derived from this privilege. The financial privileges were the most important of these. They were exempted from the tax on revenues (taille), the transaction tax on imports and exports (aides), the tax on salt (gabelle), and tolls, and in addition to this, they were freed from having to perform guard duty on the walls at night.

The financial privileges were important for merchants. Indeed, an investigation of the biography of the messengers, a prosopography, shows that some of them had another profession in addition to their work as messengers. Some of them, for example, were laboureurs, or people who “tilled the earth” (possibly a laboureur de vignes), and craftsmen like weavers and cobblers. Another belonged to the ars fabrilis, presumably a blacksmith. But there were also messengers who were merchants to an even greater extent such as a butcher, an innkeeper and a pharmacist. The largest group of messengers was from the book trade, namely printers, booksellers and publishers.

Persons with these professions had to undertake long journeys to sell or obtain their products. Thus the book dealers sold their books at the trade fairs and markets, and the innkeepers provided themselves with wine from the wine-producing areas – all without needing to pay taxes or tolls on their products. The linking of private commercial business with official work as a messenger was extremely practical. A synergy of this kind was typical for that time, in which it was generally the case that anyone who went anywhere on a journey conveyed letters or goods with them for other people.

The extensive privileges gave the merchants among the messengers a considerable competitive advantage. It is said that some of the messengers of the University of Paris were among the wealthiest citizens of Paris at the beginning of the sixteenth century.

Attempts to reduce the number of messengers

The messengers attracted envy, not only from their competitors but also from the citizens of Paris, who complained that the messengers did not have to stand watch on the city walls at night, unlike them. They did not understand why the messengers enjoyed the privileges of the clergy, even though many of them were not clerics. It also became increasingly clear to the king that he would lose tax revenue if many messengers obtained these privileges. As a rule there were 160 messengers of the University of Paris at any one time in the last third of the fifteenth century. In addition, there were many people who made themselves out to be messengers, but who in fact were not, being so-called “false messengers” (falsi nuncii). It was above all the tax authorities who attempted from the middle of the fifteenth century to reduce the number of recipients of privileges among the messengers of the nations. They started to harass messengers on the streets, at bridges, in the markets, in all places where tax collectors were active. They asserted that they were false messengers and demanded that they pay taxes and tolls even though these persons could produce a letter from the university confirming their status as messengers.

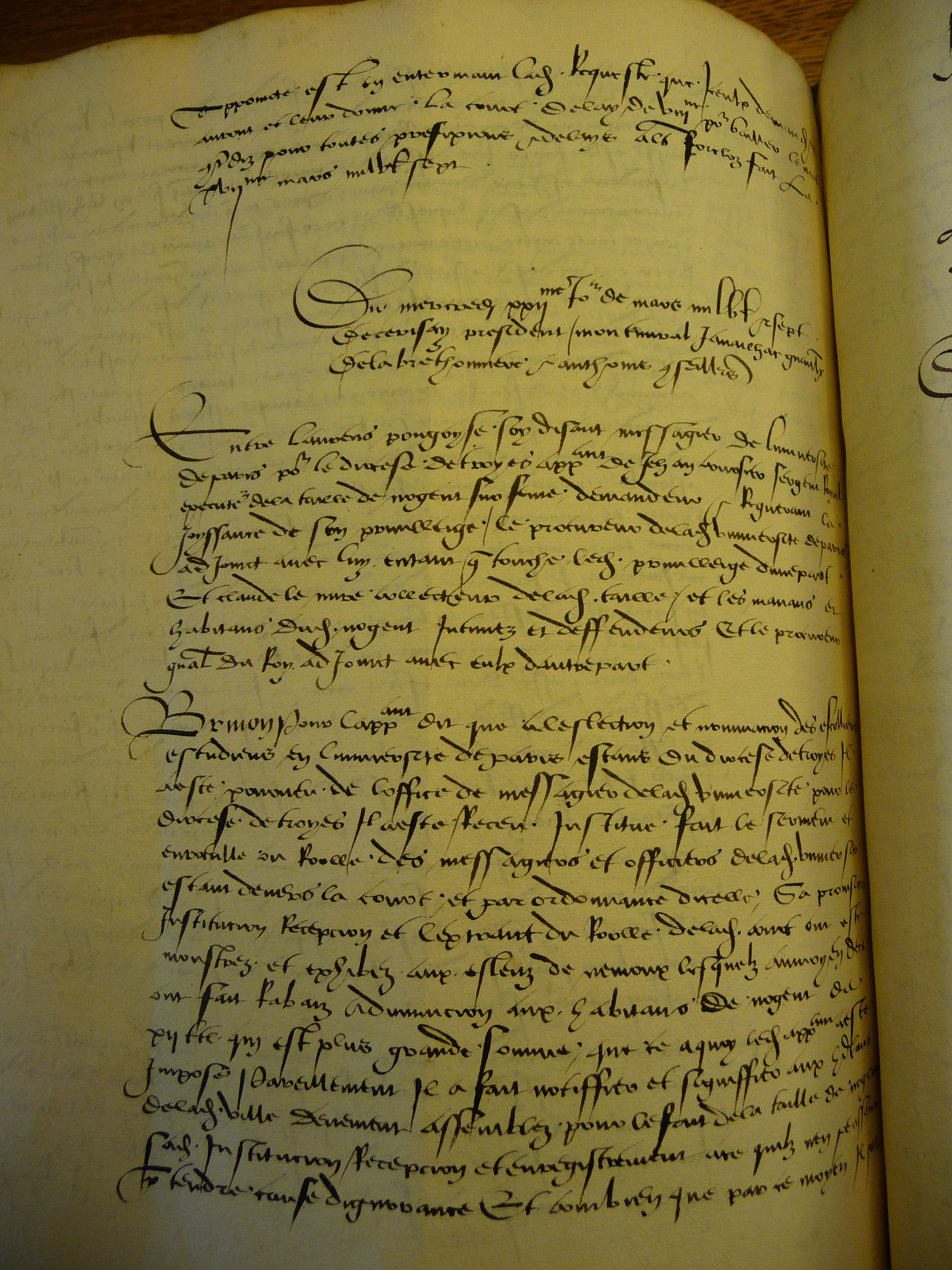

This resulted in a considerable number of legal proceedings at the court for extraordinary taxes, the Cour des Aides, the files of which are in the French national archives. They include summaries of the court cases in the form of “minutes.” An example of such a case is provided by the appeals proceedings of Lambert Pongoyse, who was the messenger for the diocese of Troyes, before the Cour des Aides in 1507. The tax collectors demanded that he pay the amount that he had been exempted for from the tax on revenues (taille) because he was so rich and did so much trade. However, in the last resort the privileges of the messengers were not really a matter for debate within the perceptions of the time and these could not be withdrawn. Pongoyse won in court, as did most of the other messengers as well.

From the minutes of the court case:

“[…] With another verdict of the Cour des Aides of 15th December 1509 it was thereby determined that a messenger of the University of Paris enjoys the privilege of exemption from the taille, in accordance with the privileges of said university and those belonging to it, as long as he exercises the office of messenger for said university for the diocese of Troyes without deceit. The inhabitants who have charged that he should pay the taille state that in fact he lives in Nogent-sur-Seine and not in Troyes or Paris, and that he is one of the richest and most powerful inhabitants of Nogent and trades extensively […]. Their statements were accepted by the Procurator General, with the result that the lawsuit of the messenger was rejected. But the Cour des Aides did not follow suit, it freed the messenger from the taille” […] (Auger, Traité sur les tailles et les tribunaux qui connoissent de cette imposition 1/3, Paris 1788, p. 199) (translated from the French).

The founding of the fraternity of the messengers of the French nation

The messengers of the nations found themselves in an anomalous position as a result of the legal and personal attacks on them. This was also true at the university, because unlike the other servants they often were not there but instead were traveling. Their special position is one of the reasons why they joined together in a fraternity in 1479. This was a professional association, and it was only open to the messengers of the Gallic nation, who evidently wanted to promote their business interests in this way. The fraternity was dedicated to the Virgin Mary and Charlemagne, who at that time was viewed as the founder of the university. Perhaps there was also the assumption that the emperor himself had created the office of messenger at the University of Paris, as people believed in the sixteenth century.

The fraternity of the messengers was headed by three colleagues. New members had to pay an entry fee amounting to sixteen sous and also make an annual payment. The center of the fraternity was the church of the Trinitarians in Saint-Mathurin in the Quartier Latin. The gatherings of the French nation took place here, and in the Middle Ages most of the messengers were taken here into this nation.

According to a source from the seventeenth century, the members of the fraternity of messengers celebrated Mass there on Sundays at the altar of Charlemagne. It was the custom as that time to organize such things with a religious connection that had its basis in faith and a church service. In addition, a fraternity fulfilled social functions, it looked after the sick and the needy, and commemorated the dead. The fraternity also provided a religious and social focal point for those messengers who did not come from Paris when they were in the city.

The importance of the transport services of the messengers of the nations

The organization of transport services on the basis of dioceses, which reflected the administrative structure of the church, and also their extension deep into the far corners of Europe, which reflected the regions of origin of the university members, made the labor of the messengers of the nations very important. It should come as no surprise, then, that the later messageries of the nations, which developed from the institute of the messengers of the nation in the beginning of the sixteenth century, were taken over into the French royal mail in early modern times through leasing.

The transport services that the messengers provided for members of the university were perhaps sometimes infrequent. But they did permit a basic level of communication, which was of fundamental importance, especially for the poorer members of the university, because the messengers were refunded with privileges. Though today we can no longer determine the number of people who derived a benefit from messengers of the nations, we can say that their services were available (at least in theory) to a large number of people. An estimated three thousand members of the university could have used messengers of the nation. Moreover, their relatives, their parents, friends and acquaintances could also use their services. In comparison to other transport systems of this time, an unusually large number of people could have participated in the institution of messengers of the nations of the University of Paris. For this reason, it was of great importance. These messengers bridged long distances, and maintained a communication network through the greater part of Europe.

Sources

Arch. Sorb., Reg. 1, f. 224v-225r

Arch. Sorb., Reg. 9, f. 1r

Arch. Sorb., Reg. 91, f. 84v

Arch. Nat. Z1a 35 f. 364v

Auctarium Chartularii Universitatis Parisiensis:

1-2 Liber Procuratorum Nationis Anglicanae (Alemanniae) in Universitate Parisiensi1-2, ed. H. Denifle and A. Chatelain, 2 Bde., Paris 1894-1897, Neudruck1937

3 Liber Procuratorum Nationis Anglicanae (Alemanniae) in Universitate Parisiensi, ed. C. Samaran, A. van Moé and S. Vitte, Paris 1935 (Auctarium Chartularii Universitatis Parisiensis, 3)

4 Liber Procuratorum Nationis Picardiae in Universitate Parisiensi, 1: 1476–1484, ed. C. Samaran and A. v. Moé, Paris 1938

5 Liber Procuratorum Nationis Gallicanae (Franciae) in Universitate Parisiensi, 1, ed. C. Samaran and A. v. Moé, Paris 1942

6 Liber Receptorum Nationis Anglicanae (Alemanniae), Bd. 1: 1425–1494, ed. A. L. Gabriel and G. C. Boyce, Paris 1964

Secondary references

M. Auger, Traité sur les tailles et les tribunaux qui connoissent de cette imposition 1/3, Paris 1788, p. 199.

Antoine Destemberg, Les messagers de l’université de Paris à la fin du Moyen Âge: jalons pour une histoire à faire, in: Revue historique 678 (2016), p. 267-295.

Martina Hacke, Aspekte des mittelalterlichen Botenwesens. Die Botenorganisation der Universität von Paris und anderer Institutionen im Spätmittelalter, in: Das Mittelalter 11 (2006) 1, p. 132-149.

Martina Hacke, Das Botenwesen der Universität von Paris im 15. Jahrhundert, in: Rainer Babel (Hg.): Aspekte der frühneuzeitlichen »Kommunikationsrevolution«, in: Francia 34/2: Frühe Neuzeit. Revolution. Empire 1500-1815. Atelier, Ostfildern 2007, p. 217-232.

Martina Hacke, Die Boten der Nationen der Universität von Paris von den Anfängen bis zum Ende des Mittelalters. Entstehung und Ausgestaltung eines universitären Kommunikationsinstituts, Husum 2019 (Historische Studien 513) (in print)

Martina Hacke, The Messengers of Nations of the University of Paris and the Book Trade (late 15th – early 16th cent.), will appear in: Mordechai Feingold, Anja-Silvia Goeing, Glyn Parry (Hg.), Worlds and Networks of Higher Learning: Universities, Academies, and Colleges, 1450-1750.

Martina Hacke, Wer partizipierte am Kommunikationsinstitut der »Boten der Nationen« der mittelalterlichen Universität von Paris?, in: Diotiama Bertel u.a. (Hg.), Junge Perspektiven auf Partizipation in Geschichte und Gegenwart. Beiträge zur ersten under.docs-Fachtagung zu Kommunikation, Wien 2016, p. 209-220.

Eugène Vaillé, Histoire générale des postes françaises, Paris; 1: Des Origines à la fin du Moyen Âge, p. 220-260; 2: De Louis XI à la Création de la Surintendance Générale des Postes (1477–1630), p. 231-247.

Martina Hacke researches the history of the University of Paris, and the history of communication (messengers, envoys) in the Middle Ages.