Remembering the dead, from folklore to political action

Soraya

In 2013, Soraya was a 25-year-old Chilean woman. She had studied at the Universidad de Chile and had just earned her bachelor’s degree in visual arts. Her future looked bright. In February, Soraya went on holiday in Chile with David, her boyfriend for eight years. They had several wonderful experiences during the warm Chilean summer, and on Friday, February 8, they traveled from Maipú to Coquimbo along the coast. They wandered around the town in the afternoon, and at the beach, David took a photo of Soraya with the town in the background. From there, they went to shop at a supermarket.

They never reached the market. At a nearby highway, Route 5, 21-year-old Sebastián Vilchez, driving his mother’s brand-new white Nissan Sentra, came off a side road. Even though the road went through the center of the town, he was driving so fast that he could not control the car. He drove off the road and into a nearby green area just in front of the supermarket. Soraya and David heard the noise from the car behind them, but before they could turn around to see it, they were struck. David was seriously injured and taken by ambulance to the hospital a few hundred meters away. The doctors saved his life, but Soraya was killed immediately; on the green grass, her body was covered by a black carpet.

After the funeral for Soraya Olivares Pizarro back in Santiago, her family created a memorial, an animita, at the place where she was killed. Soraya’s animita is a little white house with a nameplate, a Chilean flag, and a cross on the roof. Her family visits it frequently, cleaning the area around it and keeping her animita looking pretty with fresh flowers.

Animitas in popular culture

Setting up animitas is a very common tradition all over Chile. It is also an old tradition, and these visual histories of road fatalities are seen on every road. At the most dangerous places on certain roads, animitas can be seen next to each other, shoulder to shoulder. There are many thousands of them all over Chile.

Animitas are not official in any way. The authorities in charge of roads and highways have no regulations regarding animitas, but they allow people to put them up. Often in town centers with narrow streets, there can be arguments about an animita. Yet the authorities do take care of them; for example, if a road will be undergoing maintenance or construction, the authorities put the animitas aside and then replace them when the roadwork is completed. The churches have no relationships to animitas either. Many animitas display a cross, but no priests or other church representatives take part in celebrations at the animitas.

The animitas represent a living tradition in the popular culture of Chile. Not all families create an animita to honor a person killed on a road, but many do, and this tradition can be seen in all areas of Chile – at the coast, in the mountains, and in the towns. Many of the most educated people in Chile probably don’t follow this tradition themselves, but even they have relatives or friends whose lives were taken from them on a road and who have an animita to remember them by.

The word animita comes from the Chilean word ánima – in English, soul. According to some popular faiths, the souls of the dead who lost their lives through tragic circumstances wander around the area where they were killed. This belief can partly explain why family members and friends create these small houses where loved ones can place a lighted candle for the person who died. People who are not related to the person who was killed can offer a prayer at the animita; in this way, animitas can take the roles of popular saints in the Catholic religion.

Animitas are raised not only where people have died in traffic accidents. There can also be animitas for workers who were killed in a mine, executed criminals and politicians, and victims of rape who were murdered, among others. For this reason, the Catholic Church does not officially recognize animitas as part of its official system of saints. However, common people do not recognize this difference, and they continue the practice of establishing animitas as an accepted tradition. In this way, the church and the animitas co-exist peacefully. Roadside shrines dedicated to officially recognized saints do exist in Chile as in other Catholic countries, but these are rather rare. Furthermore, since animitas turn a public place into a sacred space, some of them are developing to important unofficial saints. For example, if a person finds that a prayer he or she has offered at an animita results in a particular outcome, he or she can place a plate with thanks for help near the animita. With many plates, an animita may become a well-known place that is like a kind of church. One such animita known as ‘Romualdito’ near the Central Station in Santiago is for a person who died in 1930, although not as a result of a traffic accident.

Animitas around the world

These memorial shrines are an established part of the culture in many other countries as well, although the name animita in relation to the existence of a soul is used only in Chile and Peru. In Argentina, similar places honoring the dead are called capilla – meaning chapels. They can be found in Paraguay, Peru, Venezuela, Brazil, and many other countries in South America. Wayside shrines exist in other parts of the world as well and can be seen in Japan, in the United States, and especially in Catholic regions of Europe. They are usually erected to honor the memory of a victim of an accident.

Roadside memorials are considered to be folk art by many. According to Estevan Arrellano, New Mexico’s Hispanic descansos (resting places), “. . . are created out of love in a time of pain and wonderment” (New Mexico Magazine, February 1986). He found them to be examples of the few remaining and authentic examples of noncommercial folk art, adding that they are “sculptures, in a sense earthworks, for they occupy a unique relation to the land and the environment. . . Only out of true love does a work of art evolve.” In the US, emigrants from Mexico are spreading the tradition of the descansos, and an official report on road safety from Australia surmises that one in five road-related deaths are marked by roadside memorials. In both Australia and the US, official roadside crash-marker programs have been created, although

sometimes authorities take the opposite view, removing memorials and/or passing legislation banning or restricting roadside memorials. However, the tradition and popularity of such memorials in other countries has never been as widespread as the animita tradition in Chile.

It is interesting to note that in the twenty-first century, animitas have found a new home on the Internet and on social media. Memorial sites are created on blogs, YouTube, and Facebook pages. These virtual memorials to the dead complement the physical animitas and can represent a new kind of mediation between God and humankind. However, the numbers of visitors to such memorials are not large; YouTube videos are probably only interesting for a short time following an accident.

Animitas in Chile – a photographic journey

(4) Thousands of animitas are placed along Chile’s roads. Most are small, but with flags, such as on this animita, travelers can’t avoid noticing that here a life ended.

(5) This simple animita in the countryside is very typical. Plastic flowers have been placed in vases around it, and there is a cross on the roof. This animita does not have a nameplate.

(6) Very seldom are two animitas equal in their visual presentation. This one found on a road in the countryside has small white buildings on a layer of grey stone.

(7) More ambitious buildings can be constructed, as seen in this animita from the countryside near the Chilean Los Angeles.

(8) A new trend in decorating animitas has been to show the means of transportation involved in the accident. For example, this simple animita at the side of National Road No 5 – The Pan-American Highway – near Talca shows the dangers of riding a bicycle on a highway with a speed limit of 140 km per hour.

(9) The three young men who died here have small toy cars decorating their animita, which is in the center of the Chilean coastal town of Los Vilos. In the middle of the night, they drove into a parked car at a high rate of speed and were burned to death. With the stones in blue and marble, this animita has a special design.

(10) (11) This highway in the Atacama Desert has been called one of the most boring roads in the world. In some areas, the average annual rainfall is zero – for centuries. Driving for hundreds of kilometers that all look the same causes numerous accidents. The driver behind the first animita, Juan, was probably driving petrol to the largest copper mine in the world, the Anaconda mine.

(12) In the center of Santiago, this animita is dedicated to Francisco Contreras, which was killed by a bus owned by the local bus company. The bicycle is painted white, and this has become a new tradition for many bicycle accidents.

(13) Animitas like this one seen in the countryside near Talca are created in a real folk art style. Juan Zuñiga was apparently killed in his car, and his relatives have given him several central parts from a car. Many animitas are a total contrast to official cemeteries with their almost anonymous and uniform crosses and nameplates on a green lawn. At the animitas, the personality of the deceased can be expressed in many ways.

The unofficial saint for truck drivers

(14) Two animitas in the countryside near the Andes have been given a special place. At first sight, it looks like a collection place for recycling water bottles. But the bottles are filled with water, and a steady stream of visitors offer a little pray at the animitas when they place their bottles there. The explanation is straightforward. There is an unofficial saint for truck drivers, and she is honored by a bottle of water.

The historical explanation is linked to a folk tale that goes back to the 1840s, when Deolinda Correa died. Her husband was recruited in the Argentine civil wars, and because he was sick, Deolinda tried to find him. She took her infant child with her and followed his tracks out into the desert. When her supply of water ran out, she died.

She was found some days later with her baby still alive, nursing from the deceased woman’s breast. This story evolved to become a myth that slowly transformed Difunta (deceased) Correa into an unofficial popular saint not recognized by the Catholic Church.

Her followers believe that she can cause miracles. People like cattle keepers spread the story and made small altars to her. Later Deolinda Correa became Difunta, the truck drivers’ saint. At her grave in Vallecito, Argentina, one of the largest places for saints in this part of the world has been created. Around the grave, 17 chapels are filled with offerings. It is claimed that up to 200,000 people have visited her grave on an All Souls’ Day. The two animitas on the photo from Chile have taken over this tradition.

Halloween and animitas

In the days leading up to Halloween, many animitas on the sides of Chilean roads are cleaned, painted, and filled with new flowers. Often an elderly person was seen doing this job accompanied by a child. Halloween is a contraction of All Hallows’ Evening, also known as All Saints’ Eve. While many join in the commercial festivities, such as carving pumpkins into jack-o’-lanterns, letting children dress up in costumes, and creating haunted-house parties for young people, All Hallows’ Eve is part of a more serious event in Chile. On the first of November, known as El Dia de los Difuntos, many families gather at cemeteries to put flowers on the graves of their family members who have died and to remember the deceased. The night before Halloween – called La Noche de Brujas in Chile – is celebrated as it is in many other parts of the world.

Dangerous roads in Chile

It is very dangerous to travel on the roads in Chile. In 2012, a total of 1,980 people were killed on Chilean roads. Among the OECD members, Chile had the highest rate of road fatalities per 10,000 registered vehicles in 2013 – more than five fatalities per registered 10,000 vehicles compared to the average under one. Little progress in reducing this number has been made. In 2013 compared to 2000, the rate has been reduced by 10%, while other countries have reduced their numbers of road fatalities much more radically. For example, Germany has reduced its number of road-related fatalities by more than 50% and Spain by 70%. The attitude toward safety among car owners is not high and can be measured through the use of seat belts. Only 15% of the rear seat belts in cars are used in Chile compared to 98% in Germany. In addition, 20% of Chilean drivers and 30% of their front-seat passengers don’t use seat belts.

Legislation related to key safety issues is more liberal in Chile than in most other member countries of OECD. The speed limit in urban areas is mostly 50 km/h, but it is 60 km/h in Chile. On ordinary roads, the speed limit is normally between 80 and 100 km/h, but in Chile it can be as high as 120 km/h. Furthermore, when local speed limits have been made at dangerous areas of the road, they are announced as “recommended”; it is not compulsory to slow down and follow the advice. In addition, many roads are called “motorways” but buses and shared taxis regularly stop for passengers, and there are many shops and side roads on these roads. Furthermore, bicyclists and pedestrians use the “motorway” because of a lack of alternatives. In regard to driving while impaired by alcohol, the maximum permissible blood-alcohol content is 0.3 g/l for all drivers. This almost zero-tolerance policy brings Chile into the group of countries with the most stringent policies. However, in 2012 it is estimated that 14.2% of fatalities involved a driver impaired by alcohol. Chile has the dubious distinction of being the country within the OECD with the most dangers on its roads. Compared to countries that are not members of the wealthy OECD, Chile is actually one of the better ones in regard to road safety. While Chile had six fatalities per 10,000 vehicles in 2010, the Central African Republic had 1,347, Benin had 828, and Sudan had 937.

Killing a person in a vehicular accident is murder

The relatives and loved ones of Soraya Olivares Pizarro went further than creating an animita in her memory. They didn’t find that her death was caused by supernatural forces or a random act of fate. It was not an anonymous road accident that added one more number to the statistics. To them, it was a murder committed by a man driving too fast that ended the life of this beloved young woman. Family and friends joined the lawsuit against the driver. Outside the courthouse, they carried signs calling for punishment of the guilty driver. Inside, they sat wearing tee shirts that read “Justice for Soraya.”

(15,16)

The young driver admitted his guilt. His punishment was 540 days in prison, but because he admitted his guilt, the punishment was conditional, allowing him to walk from the court as a free man. The family and friends of Soraya did not think this was justice. If the driver had caused an accident that killed a woman because he had been drinking, he should spend five years in prison. They have since worked on campaigns to make drivers responsible for the accidents they cause to others.

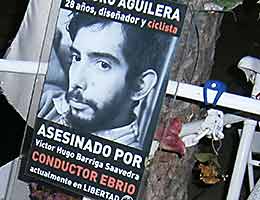

Other groups have reacted in the same manner. The previously mentioned accident that killed Francisco Contreras gave rise to political action as well. An action group, “Ciclistas con Alas” (bicyclists with wings), printed posters with a photo of him and the words (translated): “Francisco Contreras, 24 years old, worker and bicyclist. Killed by Alonso Roberta Rodriquez Valenzuela, a reckless driver, actually not jailed.” Another bicyclist who was killed has a similar poster at his animita, and the poster for Arturo Aguilera states that he was killed by a drunk driver. Many similar groups have joined together in the organization “Organizaciones Ciudadanas de Seguridad Vial” OSEV (citizens’ organization for road safety). On the international level, a dozen South American countries have worked together in an organization for victims of traffic accidents since 2010.

Animitas as traffic safety propaganda

In Chile, a country with a growing number of private cars, an enormous effort is necessary to reduce the number of traffic accidents. The governmental body Comisián National de Seguridad de Tránsito, CONASET (Commission of Road Safety) is using every means to create awareness about the problem. In 2011, CONASET launched a campaign called “Manéjate por la vida.” As part of this campaign, hundreds of animitas were installed in unusual places around the capital city of Santiago to remember those who died and also to evoke the pain and suffering of the families who have lost loved ones in road accidents. The campaign includes a number of actions designed to prevent road accidents; among them are raising awareness about the importance of wearing seat belts, controlling speed, good visibility, and not using alcohol if you are going to be operating a motor vehicle.

CONASET has established strong cooperation with organizations such as the OSEV to work for a healthy culture concerning driving and road safety. One action took place on the first of November – All Saints’ Day – when 2,500 people joined the “Second National Road Safety Run for 2015,” a festival to raise public awareness about traffic accidents. The aim was to generate safe road habits, and before and after a mini-marathon in the streets of Santiago, the runners could hear advice on how to drive safely. At one stand, OSEV members told their tragic personal stories.

Then, 15 days later, CONASET and OSEV joined the “World Day of Remembrance for Victims of Traffic Accidents” that was declared by the UN in 2005 to raise community awareness. The event took place at one of the most heavily travelled places in Santiago at the Central Station. Activities included several for children such as a play about safety, stands with educational road-safety messages, and performances by popular artists. Many relatives of those killed as a result of traffic accidents carried posters with photos of their loved ones with their names and the year the tragic accident took place. Remembering the dead had evolved from creating folk art animitas on the side of the road to national political action.

Jørgen Burchardt

Photos: Jørgen Burchardt and Anne-Grethe Andersen (4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 13, 14), family Olivares Pizarro (2, 3, 15), Esteban Zamorano (12) and CONASET (17, 18).

Jørgen Burchardt is researcher at the National Museum of Science and Technology and has former been director of the Danish Road Museum. He is currently working at the project “Freight transportation and supply chains 1920-1980”. His background is an education as engineer followed by studies in ethnology at the University of Copenhagen and continuing education at the Royal Institute of Technology, Sweden and Deutsches Museum, Germany. Latest works are “Danske veje i Ghana” (Danish roads in Ghana), Vejhistorie, 2015, “Walker Danmark – fra håndværk til multinational business” (Work and management in the exhaust system business) 2008. “En rullende revolution – ballondækkets historie” (A Rolling Revolution – the History of the Balloon Tire) Årbog, 2008. (With M. Schönberg): “Lige ud ad landevejen.” (The history of the Danish highways 1868-2006). 2006, 383 p. Danish Road- and Bridge Museum.