Claudine Moutou

The University of Sydney

Since my last visit in 1989 to the island of Mauritius my sensitivity to the sights has changed. This time I was not just sensitive to places and artefacts that had meaning to the lives of my family (living and deceased) – including reported sightings of the green and white Vanguard that my grandfather previously owned. This time I was sensitive to observing how mobility and the organisation of transportation services differ from that which I am accustomed to (in Australia), and what these may mean for Mauritius’ future.

The island of Mauritius is 2040 square km with a population of 1,257,121 (Statistics Mauritius 2012). From the air Mauritius can be appreciated for its image as a tropical honeymoon destination. The interior consists mainly of sugarcane fields and mountains bordered by white sandy beaches and the intense blue of coral reefs. The population is largely found in an arc stretching from the capital Port Louis down to Cure Pipe in the central west of the island. It is no accident that these population centres follow the route of the Midlands railway line originally built in 1865. What is surprising is that transport technology that contributed to the pattern of urbanisation was abandoned. The last passenger service was in 1956 and eventually the railway network was dismantled and sold off.

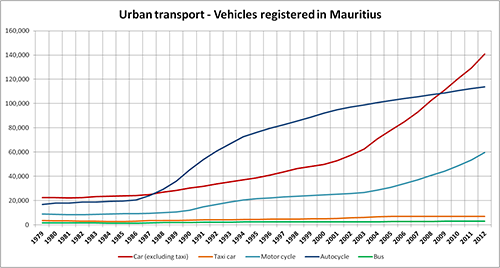

In 2013, urban transportation in Mauritius is well and truly motorised. My memories of 1989 include the beeping of horns as drivers sought to clear the road of cyclists and dogs. Since my visit in 1989, the most dramatic change in types of registered vehicles is not so much the growth of privately owned cars – but the large number of autocycles that provide a fast and cheap form of mobility. While the number of cars (excluding taxis) appears to surpass autocycles in 2009 it is coupled with a growth in motor cycles. As seen in the graph the growth in taxi cars and buses is almost non-existent.

Figure 1: Selected modal longitudinal data sourced from Statistics Mauritius (2012)

Taxis in Mauritius are not as intimidating as I remember them in 1989. They were to me a mystery. I would see a taxi car packed with passengers pause by the road side. One person would get out and another three would get in. In 2013, there are now clear visual cues to recognise a taxi and how they

operate. They are uniform in look. Standard white sedans each with a yellow rectangle identifying the name of the town taxi rank that they belong to. Observing this consistency and regulated systems gave me a level of comfort and reassurance had I needed to use a taxi. It did not however act as a deterrence to wannabe taxi drivers who beeped their horns trying to get a fare from us as we waited at our bus stop.

I have no memories of buses in 1989 but in 2013 I found travelling the bus system relatively easy. The transport network on an island the size of Mauritius is focused on the linking of towns, not neighbourhoods within a town – thereby making it easy to identify which bus to take. Bus stops are inconsistent in design but easy to recognise. Some of the bus stops along busy routes had corporate marketing to help them stand out, as seen below.

It is the workings of the bus system – the impressive and perplexing aspects – had the biggest impression on me in this trip to Mauritius. These can be summarised as being about either the passenger experience or bus system constraints to improvement. I did not find timetable information at bus-stops and didn’t have a chance to feel concern. The buses demonstrate high levels of service frequency – albeit during the day – and staff at bus stations always answered my questions (“5 minutes”). But as I rode more buses I wondered if the lack of timetable information was being exploited by bus operators at the expense of passengers’ time and safety. When timetable information is not available buses have the flexibility to collect as many passengers as possible before their competitor. This appeared to be at the expense of passenger safety and the value of passengers’ time as I observed while travelling around the island in car and on bus that on less busy routes bus operators had a tendency to pause for extended periods of time at bus stops in the urban areas, and then speed through the countryside.

Bus safety and maintenance is an issue of concern. Public transport in Mauritius is operated by a combination of operators – a government run National Transport Authority, seven private bus companies and 11 bus owners’ co-operatives. It is no exaggeration to say the bus fleet, including those run by the government, is old and, as evidenced by the exhaust smoke, poorly maintained. The variety of vehicle designs and livery may be delightful in the eyes of a tourist but not for passenger comfort. Air conditioning is virtually non-existent, many buses have steep stairs and there is no room for wheelchairs or prams. The first low-floor buses to be introduced by one of the private companies and marketed as a premium-service with functioning air-conditioning and subtitled films showing as on-board entertainment – which even managed to distract this transport enthusiast from looking out the window.

Photo 5 & 10: A branded bus shelter and steep stairs for boarding a bus (Source: Moutou)

External pressures are a significant constraint to improving the operation of the bus system. The roads through towns are narrow thereby providing no space for separate lanes for buses. Space is at a premium especially in the capital Port Louis. The encroachment of ‘illegal’ street traders onto the road space in the city centre narrow streets is a political issue. What surprised me was that it was allowed to extend into the roadway of the two Port Louis bus stations. I was witness to street traders blocking the passage of buses within Gare Victoria – a bus station already heavily congested with bus queues. Chaos reigned as both buses and street traders want to serve the rush of workers leaving work to catch their bus home. While this is reportedly going to change soon with the creation of more market space, the low regard for the bus timeliness, the poor regulation of space within the bus station and the seemingly public acceptance of the situation was puzzling.

Photo 11: Snapshot of peak hour at Gare Victoria as street traders are in no rush to move (Source: Moutou)

Bus operators in Mauritius have to contend with the pressures of competition from other modes of transport. Aside from the competition of private car ownership which for many Mauritians, as in other parts of the world, is viewed as evidence of their climb up the socio-economic ladder, there are plans underway to add lightrail. The métro léger is proposed to link Port Louis to Cure Pipe, the busiest commuter route as the heavy rail once did. Buses are expected to act as feeder services which will necessitate a change in the bus network but also the profitability of different routes. Bus operators will need to contend with greater competition for passengers but their ability to prepare is stifled by the limited information as the project goes out to tender. It is not clear, for example, how much of the space of the transport interchanges will be allocated to park-and-ride and to buses. If light rail stops will be located within towns – therefore causing a high level of reorganisation and disruption to existing land-use and transport operators, or on the periphery of towns away from established trip generators. Bus operators will also need to remarket their services as information about bus routes will need to be communicated and customer expectations about comfort and safety change. This will be difficult for many bus operators who have been relying on public acceptance of any bus service being better than a modern bus service. But it is a challenge that is worth facing if Mauritius is avoid increases in car ownership placing pressures on the natural environment that it relies on so much for its economic wealth.