Maintaining Safety Through Regulatory Enforcement

Lee Vinsel, Virginia Tech

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- How Can Danger Go Unnoticed?

- Crash Tests as Necessary Work

- Instrumenting a Car for Crashing

- How to Standardize a Wall

- Fiat’s Non-Conforming Testing Grounds

- Keeping Dangerous Technologies Off the Road

- Notes

Introduction

Ashley Parham was eighteen-years old and had just graduated from high school in 2009, when she went to pick her younger brother up from football practice. She was driving around the parking lot looking for a space when she accidentally bumped into another car. The minor collision was just significant enough to deploy the airbag. But something went wrong. Not only did the airbag fail to inflate correctly, it also threw metal shrapnel at Parham, slicing her carotid artery, leaving her bleeding to death. When police found her, they thought she may have been murdered. Instead, she was likely the first victim of defective airbags produced by the Takata corporation that, in time, led to one of the largest recalls in history.

In April and May of 2013, BMW and a range of Japanese automakers recalled millions of vehicles containing these airbags. A year later, Ford, Chrysler, and several other companies announced that they too were recalling millions upon millions of cars. Eventually, these defective airbags would be linked to at least 12 deaths and hundreds of injuries in the United States alone. Over 60 million cars would be recalled before it was all over, and in 2017, Takata folded in bankruptcy.

Later investigations uncovered that some automakers knew the airbags could be defective for more than a decade. This discovery led some people to ask, how could defective technologies that violated federal law be sold for so long without the authorities becoming aware? Answering that question requires us to think about all of the work regulators do to enforce safety standards—work that is at best imperfect and whose successes and failures often hinge on luck. Regulators and contract firms that work for the U.S. government regularly conduct crash tests and other enforcement activities to ensure that automobiles sold in the United States live up to existing rules. These activities take place out of sight. They involve largely anonymous individuals. They are messy, on-going work that is never done. And yet the safety of the transportation systems around us depend on such mundane, nameless labor. How do we bring it into view?

Crash Tests as Necessary Work

One answer is that activities come into view when something goes wrong. When things go awry in regulation—when we discover that products do not conform to safety rules—regulators and others create paper trails that we can use to reconstruct enforcement efforts. A safety enforcement and vehicle recall effort involving Fiat cars that the U.S. federal safety agency, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), conducted from 1969 to 1971, helps illustrate some general structures of regulatory work.

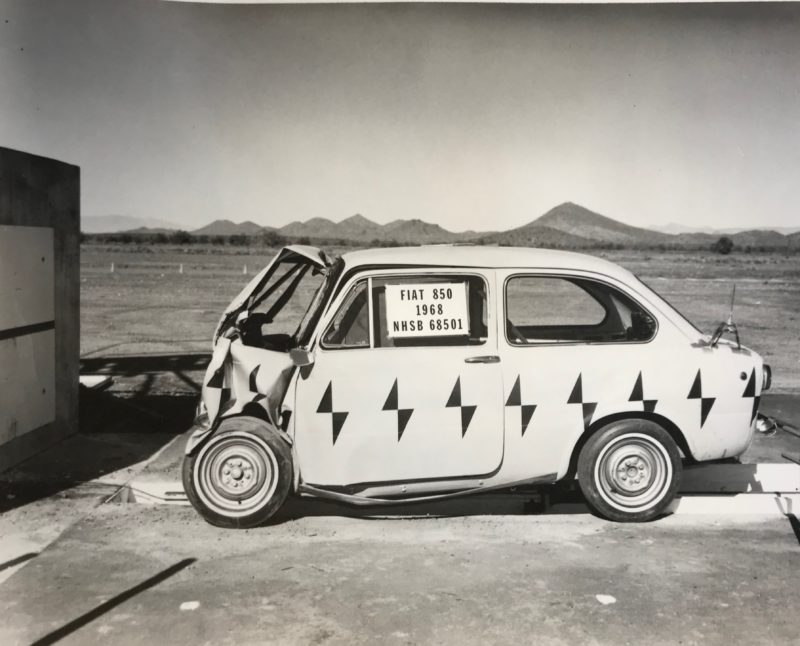

On September 24, 1969, four NHTSA staff members traveled to Los Angeles, California, to witness crash tests run by the Digitek Corporation, a private firm that did contract work for the agency.[1] They planned on testing a 1969 Fiat 850 Sedan, but their purchasing agent had accidentally sent an 850 Coupe instead. They decided to crash the car anyway, and the test did not go well for the Fiat Coupe. It badly violated a federal safety standard. This test—which was a matter of luck—began an investigation that lasted for a year and led to Fiat recalling thousands of vehicles.

Instrumenting a Car for Crashing

The Fiat car had violated Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard 204—Steering Control Rearward Displacement. Standard 204 set a threshold for the distance that the steering wheel could “displace” backwards towards the driver’s body in a front-end collision. The basic test for Standard 204 involved driving a car into an immobile wall at thirty miles per hour and measuring the rearward displacement of the steering wheel.

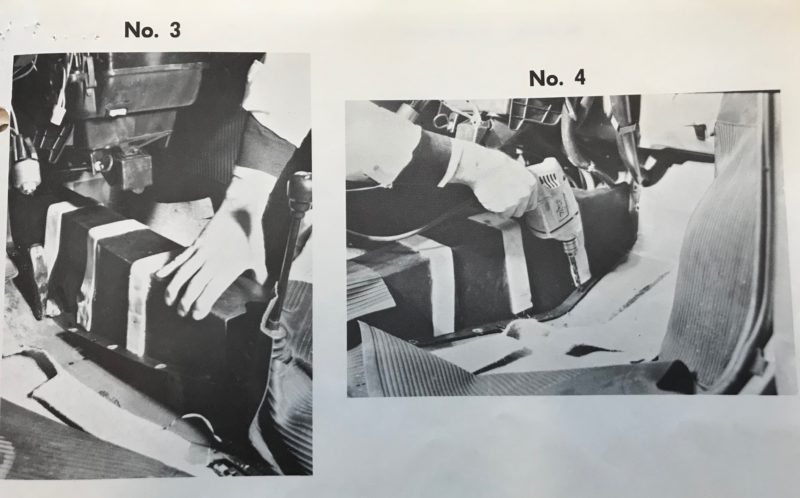

In the picture above, which was found in federal records, we can see a tester demonstrating how cars are instrumented for testing under Standard 204. Preparing the car for testing required a great deal of labor. In this case, staff members at Digitek attached a measuring device to the steering wheel and an anchor in the back windowsill. They removed both front seats and mounted metal frames that held a high-speed camera and the measurement grid that can be seen behind the steering wheel. The high-speed camera recorded the steering wheel moving in front of the grid, as car smashed into the crash barrier. Finally, when the car was successfully instrumented, they crashed the car into the barrier and began the long process of examining the resulting data, including the high-speed film, before preparing a report on the test.

Standard 204 limited rearward displacement of the steering wheel to 5 inches. In the initial test, the Fiat Coupe’s steering wheel displaced 6.75 inches.[2] In a later test, another Fiat Coupe’s steering wheel displaced backwards 9.21 or nearly twice the limit.[3] The steering wheel moved backwards so far it left the frame of the high-speed camera. It would have badly injured or killed the driver going into his or her upper-chest or head, possibly even leading to decapitation.

How to Standardize a Wall

Crashing cars may be the most dramatic aspect of federal regulatory enforcement, but the vast majority of enforcement involves white collar labor: filling out forms and producing paperwork, attending meetings and making phone calls, writing, editing, and publishing reports. When NHTSA staff members returned from observing the crash test in California, they began the work of examining the results and producing the documents that would eventually support their case against Fiat.

Federal regulators were faced with a question: Fiat had claimed in official filings that its cars met US federal safety standards, so what had gone wrong? The investigation quickly came to focus on how Fiat had done its own tests at its headquarters in Turin, Italy—most directly, the company’s failure to follow federal standards properly.

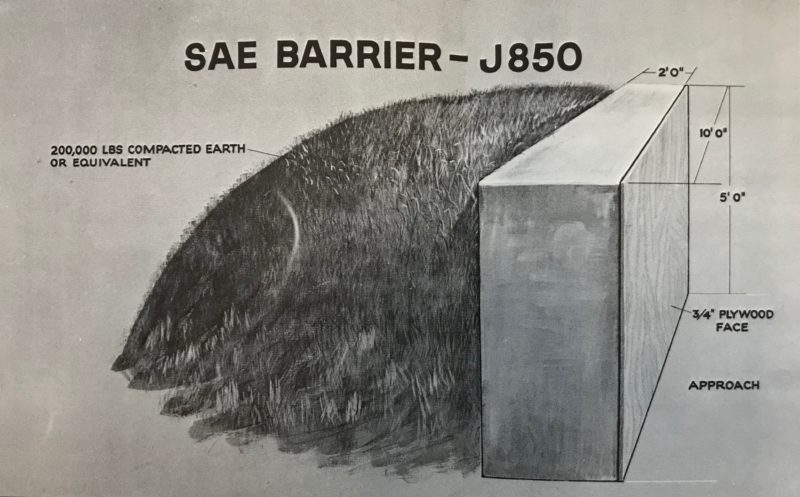

Technical standards are often complex. U.S. federal automotive safety standards brought together a variety of standards from other places to define how testers should do their work. In this way, regulatory enforcement depended on concatenations—or long chains—of paperwork developed over years, in this case, involving both committees within the Society of Automotive Engineers and regulators within federal agencies. Standard 204 included a standard from the Society of Automotive Engineers, Recommended Practice J850, which standardized the dimensions and characteristics automotive crash test barriers should have.[4] It mandated that crash test barriers should be concrete walls backed 200,000 pounds of compacted earth or the equivalent thereof. The key point is that the barrier should be immobile, pushing all of the force in the crash test into the crashing vehicle itself.

The Fiat cars were failing this test dramatically. Regulators found that, because Fiat’s cars had rear engines with trunks in front, steering wheels moved upwards at an extreme angle during crash tests, directly at a driver’s head. The injuries in such an accident would have been gruesome and catastrophic.[5]

Fiat’s Non-Conforming Testing Grounds

The regulatory investigation uncovered that Fiat’s crash test barrier and, therefore, its tests did not come anywhere near U.S. government rules. The issue was that Fiat did not have a dedicated testing facility.[6] Instead, Fiat’s leaders decided to use the runways at the company’s private airport as its test area. However, they still wanted to use the airport as an airport, flying in and out of it with private jets for company business. Having crash test barriers on the runway would be a problem for planes. For this reason, the labor of testing worked differently at Fiat than it was supposed to according to the U.S. government: testers at Fiat built temporary crash test walls out of concrete cubes. They would use forklifts to form a wall with the cubes, and then take the wall back down after the tests. U.S. regulators found that the temporary walls in fact moved during the tests, thereby absorbing some of the energy during impact. Fiat’s cars had, in effect, “passed” its own tests because Fiat employees were doing the tests wrong. In 1970, NHTSA pushed Fiat to recall and modify 9,000 vehicles which had been sold in the United States, and the agency fined the company $100,000, the largest fine to that date. Newspapers, like the Wall Street Journal, hailed the fine as a success for the federal agency with titles like, “Italian Auto Firm Allegedly Didn’t Meet Federal Steering-Column Standards; Fine is Highest Yet.”

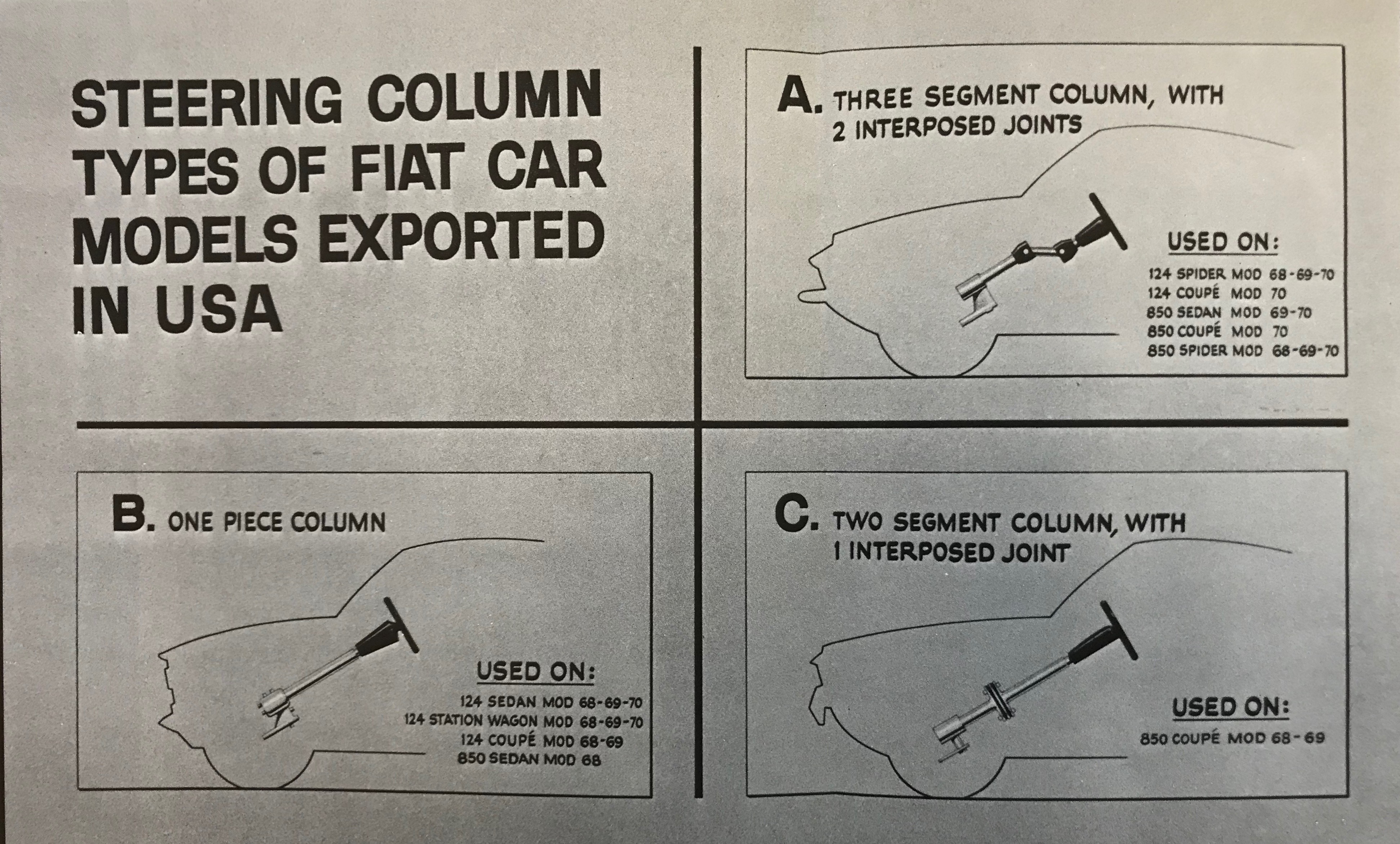

Conclusion—Keeping Dangerous Technologies Off the Road

In the end, NHTSA staff members found that, because Fiat had done the tests incorrectly, it had claimed its steering-columns to be “safe” when they were quite dangerous. So-called “energy-absorbing steering-columns” had existed in the US since the early 1960s, and Fiat had its own version, which featured three-segments that collapsed into each other upon impact. However, the company had continued importing steering-columns that consisted of single steel bars, which sometimes impaled drivers during frontal collisions.[7]

The Fiat case has several important lessons to teach us. First and most simply, it draws our attention to the crucial, ordinary work of regulatory enforcement—the labor of ensuring technologies live up to our legal expectations. Second, the Fiat case shows us how regulatory enforcement involves not only seeing if technologies conform to standards but guaranteeing that testers at different times and different places and within different organizations follow standardized procedures. It’s about standardizing the testing work as well as the regulated object. Fiat had failed to follow procedure. And, finally, the Fiat case reminds us that budgets for regulatory agencies and other government organizations matter. Enforcement and testing cost money. When we cut federal budgets, as we are doing again these past few years, we do fewer tests and have less bandwidth to enforce rules. The chances go up for dangerous technologies to be sold on the market without being discovered.

Notes

- Safety Standards Engineers to Chief of Validation Division, “Trip Report, September 24-27, 1969, to Digitek Corporation, Los Angeles, California,” October 7, 1969, 1, General records, Records of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration 1966-91, Record Group 416, National Archives at College Park, MD.

- Robert Gardner, “CIR Background Synopsis,” October 7, 1969, General records, Records of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration 1966-91, Record Group 416, National Archives at College Park, MD.

- Robert H. Gardner, Safety Standards Engineer, to Chief, Validation Division and Chief, Vehicles Branch, “Trip Report, October 29-31, 1969, to Dynamic Science, Phoenix, Arizona, and Digitek Corporation, Los Angeles, California,” November 24, 1969, 1.

- Federal Register, Vol. 32 (February 3, 1967), 2414.

- Digitek Corporation, “Vehicle Test Report FMVSS 204 1969 Fiat Model 850 VIN 0242771,” November 5, 1969.

- Letter, Robert Brenner, Acting Director, to V. A. Garibaldi, President, Fiat Motor Company, “Subject: Fiat Model 850 Coupe,” October 29, 1969, 1.

- Memorandum, David E. Wells, Chief Counsel, to F. C. Turner, Federal Highway Administrator, through Douglas W. Toms, Director, NHSB, “Fiat Civil Penalty 850 Sedan and Coupe,” March 3, 1970, 1.

Lee Vinsel is an assistant professor of Science, Technology, and Society at Virginia Tech and a co-organizer of The Maintainers, an international, interdisciplinary research network focused on maintenance, repair, and mundane labor with things. His book, Moving Violations: Automobiles, Experts, and Regulations in the United States, will be published by Johns Hopkins University Press in spring 2019.