Diary of a commuter: travelling during the Olympic Games (London 2012)

Journey options from Zone 3 to Zone 1 on the London Tube during the Olympics

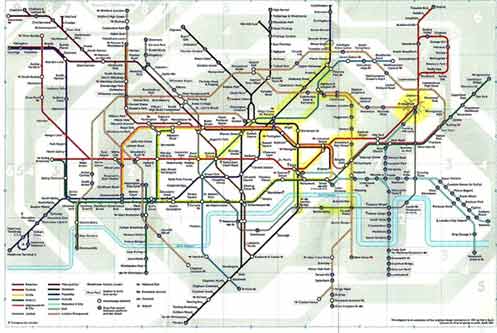

Journey options from Zone 3 to Zone 1 on the London Tube during the Olympics

One of the things that has called my attention since I came to London and became involved in the field of mobilities studies was a certain obsession about (over)planning, modelling, and forecasting practices of mobility. Having had the chance to experience the city during the 2012 Olympics has confirmed me that contingency is still “alive” undermining planning and facing us with new situations. I would have liked to give a detailed description of how London’s transport system dealt with 1 million visitors over 17 days, particularly after the bombing of messages warning about congestion and restrictions on circulation. But I have to admit that, in the end, it all boiled down to the old Shakespearean saying: it was all much ado about nothing.

Through emails, posters, advertising in newspapers and the like, Transport for London (TfL) advised commuters to avoid “travel hotspots” during the Games because some stations and underground lines would be “extremely busy”. They asked you to plan ahead your alternative routes to avoid the crowd of visitors. For a commuter like me who works near London Bridge and lives in North London, the alternatives were scarce because all the possible routes were hotspots. They also suggested cycling or walking as alternative. I used to cycle when I lived in Zone 2 and it took me 50 minutes to reach my workplace. Living now in Zone 3, it takes me about the same amount of time to get there by underground!

Photo 6: Journey options from Zone 3 to Zone 1 on the London Tube during the Olympics

Planning:

Before the Games, I had planned to take the Tube very early in the morning –about 6.30am instead of 7.30am. Likewise, my boss arranged to stay at work overnight since suppliers were going to deliver during the night due to the restrictions posed on day circulation around Central London. Instead of the van to carry the food between the kitchen and the market, we proposed to use a bicycle with a cart. Moreover, many of my friends made plans to leave London during the Games because it would be a chaos. I planned to stay at home writing instead of going to the library to avoid wasting my time. The British Library changed their timetable, opening an hour later expecting the staff to be delayed. And bus drivers went on strike claiming for a bonus because the traffic would be extremely busy.

The feeling was that rather than a party, what we were going to live was more like a nightmare. This feeling was heightened by those free newspapers you can get hold of inside the Tube. Two topics were recurring headlines: security and transport. The forecast: both will collapse. Not only 1 million people were going to come, but also all the tickets for the Games were apparently sold out. Londoners, seemingly, were preparing to assist to every Olympic event…

One of the first things that struck me months ago was a poster advertising how to avoid delays. It showed a blond adult man, wearing a suit, using a pole to jump over the crowd –getting ahead of the “rest”. The rest included other people (like an elderly lady with a shopping cart and an old Muslim man) who seemed to be unworried by time while looking at him. The poster was part of a series of ads which showed other typical office workers of “the city” finding alternatives to travel comfortable and fast. In a typical commuter’s pose (reading a newspaper) another ad showed a man going down the escalator completely alone while the other escalator was full of a multicultural mob going up. I may be reading too much into this, but aren’t these representations conveying an “ideal receptor” (the White, young, dynamic professional who works for the financial sector), while being notably gendered, classist, and also racial biased? I believe this is so, and this adds to the clear tendency to separate two types of passengers: the commuter and the visitor, which could be well read into Lefebvre’s two rhythms: the cyclical (marked by the festive) and the linear (regulated by the work time). I wondered which were the reasons for such an opposition (and division) between the City and the Games, if the former offered itself as a host to the latter, arguably pretty much on the basis of a financial rationale.

Then the Games started (Tuesday, 31 July). “The first medal gold for London transport” was the headline of a newspaper. It seemed that the public transport system had performed “normally” during what was seen as “the D-Day” (Monday, 30 July). In fact, commuting that day I was struck by the fact that I had managed to secure a seat (a quite rare event) while I read the news. I had taken the Piccadilly Line about 8 am, and changed later with the Northern, making a fast arrival at London Bridge at 8.45 in the morning and in a coach with free seats! Amazed, I notice that London Bridge station was almost empty, except for the many Olympic volunteers and TfL staff ready to guide the mob giving indications. The station’s main hall was layered with fences to conduct the flow of passengers according to the destination. Likewise, the street was not busy at all –if commuters had had decided to bike or walk, they should have been there. A couple of minutes later I learned that my bosses had not spent the night at work, and that the bike was not necessary at all (Although suppliers had found problems to circulate: one of them told me that as one lane of the street had been left exclusively for athletes, the traffic was so slow that it took 45 min to advance 500 yards).

The above describes more or less the pace at which things went on during the Olympics. I made some more notes: for example, one day I had to go near Oxford Circus, so I took the opportunity to “observe the field”, this time bringing my little son (along with his buggy). Happily, we moved comfortably, even when in the Central Line (the one which connects with the Olympic Park). In fact, although London is always full of tourists, the Games’ visitors were easily distinguished –because of the flags they carried, the orange T-shirt of the Dutch, the way they moved, or because they were asking for information to get to a venue. Truly, it can’t be said that they constituted a crowd that packed the underground car or the like. In fact, the flow of people walking on the streets or within the underground beat an unusual rhythm, one that if it wasn’t completely of a festive kind, “felt” somewhat “calmer” than that on a working day.

That situation triggered me to ask the following question: if 1 million people came for the Games, how many Londoners had left the city? It seems to me that the consequence of (over)planning was to frighten away local people. And, unwittingly, this seemed to be confirmed by a British Airways ad placed on the walls of an underground platform: “Don’t fly. Support the team GB”.

After the Games, I received the following email:

“Dear Mr Zunino Singh,

By changing the way you travelled, you helped support a great Olympic Games and kept London moving. Without you, the past two weeks wouldn’t have been possible.”

According to the TfL, there was an increase of 30% of passengers compared with the last year. But they forgot to say that for the first time since I have lived in London, all the underground lines were working without interruptions or engineering plans, a rare event once the “Good Service” sign displayed in all the underground lines is something atypical for a London commuter. Plus, the Tube was opened until 3am! And, finally, the increase was mainly registered in the DLR or the lines which go to the Olympic Park in Stratford. I’m not saying that statistics are wrong. But from the point of view of a commuter who did not change his habits, all this “thanking” sounded a bit strange. Even more when those weeks are compared with the last one, when I couldn’t find an available seat during the whole of my journey while those “City” commuters who seemed to have disappeared were suddenly back and tanned!

By Dhan Zunino Singh,

the University of London, England