Hand-Made Streets: The Role of Labor in Making, Installing and Maintaining Street Pavement Prior to the Dominance of Asphalt

Robin B. Williams, Savannah College of Art and Design

Table of Contents

- Street Pavements before Asphalt

- The Labor of Street Paving

- Cleaning Streets

- Heritage Work

- Notes

Introduction

The paving of streets with macadam, blocks or bricks represented a vital development in the modernization of cities beginning in the nineteenth century. It also represented the product of extensive and often highly skilled human labor. Images of anonymous work crews installing pavement frequently appeared in the pages of municipal reports, underscoring a city’s commitment to invest in such labor-intensive and costly public works. Occasionally the labor involved in street paving generated surprising public acclaim for individual craftsmen, most notably James Garfield “Indian Jim” Brown, whose skill and efficiency defied belief. But making street pavement successful went well beyond its installation. From the preparatory harvesting and transporting of materials and their shaping into usable pavements to their maintenance through the prominent efforts of street cleaning crews, human labor was the historical agent shaping the interrelationship of advancements in modes of transit and the evolution of surface pavements. That tradition gained renewed importance with the spread of the historic preservation movement to street pavement in the 1970s, which highlighted the importance of skilled labor needed to restore historic street surfaces.

Street Pavements Before Asphalt

Before modern synthetic sheet asphalt assumed its dominion over streets and highways in the 1920s, North American cities employed a wide array of street pavement materials. The remarkable breadth of materials was matched by the labor skills required to create and install them. Beginning with cobblestones in New York in the seventeenth century and in Philadelphia by the early eighteenth century, most cities experimented with diverse materials beginning in the 1800s depending on their geographic location, economic resources and needs.[1] Early nineteenth-century use of macadam (a kind of layered gravel) led to midcentury experiments with wood blocks, granite or sandstone Belgian blocks, and later asphalt blocks and vitrified bricks, among others, sometimes all at the same time in the same city.

The earliest municipal efforts to pave streets in American cities sought the most expedient and affordable materials and involved more brute muscle than skilled craftsmanship. Beginning in the seventeenth century, East Coast port cities made use of cobblestones, irregular naturally rounded stones that arrived in the holds of ships as ballast. To make room for the heavy loads of raw materials for export, the ballast stones were manually removed from the ships and typically deposited on a wharf, where they became a ready resource for street pavement. Princess Street in Alexandria, Virginia, believed to have been installed by Hessian soldiers, is typical in comprising a wide variety of stone types and sizes laid in a loose and random pattern (figures 1 and 2).[2] By the mid-nineteenth century, however, cobblestones began to fall out of favor as pavement experts like William Gillespie, a professor of civil engineering at Union College in Schenectady, New York, considered them a “common but very inferior pavement which disgraces the streets of nearly all our cities.”[3]

Achieving road surfaces better suited to the growing number of wheeled vehicles in industrial cities would require more skilled and intensive labor. Scottish inventor John Loudon McAdam developed a layered pavement, macadam, as it came to be known, that involved workers breaking stones to a consistent size able to be passed through a two-inch ring (figure 3). The rule of thumb for laborers was that no rock should be too large to fit into their mouth. Constructing the roadbed itself was equally labor intensive, with a layer of broken stone followed by a binder layer of some kind, such as sand, lime or bitumen, then compacted with a roller. Some macadam roads involved multiple such layers. First used in London in 1820 and in the United States by 1823, macadam enjoyed extensive use throughout the nineteenth century and even into the first decades of the twentieth century due to its relative affordability.[4] It remained in 1904 the most common type of pavement in some major cities, including Boston, New York and St. Louis (figure 4).[5] Macadam, however, was far from permanent and prompted complaints about dust.[6] In response, municipal engineers in each city experimented after 1850 with more expensive block, brick and cylinder pavements of wood, stone, asphalt and fired clay to solve the pavement problem.

|

![Diagram showing relative proportions of different types of street pavement used in major American cities in 1904. Source: John W. Alvord, “A Report to the Street Paving Committee of the Commercial Club on The Street Paving Problem of Chicago” [Chicago: R. R. Donnelley & Sons Company, Printers, 1904], exhibit no. 2).](https://t2m.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Williams_figure-4.jpg)

|

Perhaps because of the relative ease with which it can be shaped and its availability in many regions across North America, wood enjoyed early widespread use as a pavement material beginning in the 1830s. Whether cut into planks or rectangular or hexagonal blocks, wood pavements required not only the labor of loggers to fell trees and workers at saw mills, but were the first North American pavements to require the craftsmanship of carpenters or masons at the point of installation (figure 5). The use of wood cylinders, such as those in Detroit (figure 6), simplified the shaping process, but necessitated careful sorting and placement of pieces of differing diameters to minimize the spaces between them. Wood pavements were smooth, affordable and “noiseless,” but struggled, however, with durability, even when later coated in creosote (figures 7 and 8), which limited their use in most cities to streets with relatively light vehicular traffic or where reducing noise was essential, such as by court houses.[7]

|

|

Rectangular Belgian blocks, usually of granite but also of sandstone in the Midwest, emerged in the mid-nineteenth century as the pavement of choice for industrial areas where heavy traffic was most common (figure 9). Shaped by arduous hand chiseling, Belgian blocks are generally rectangular in shape and often vary in size, reflecting the manual-labor nature of its production – as seen in the paving of The Esplanade in Toronto in 1905 (figures 10 and 11). Introduced in the early 1880s, vitrified brick gradually became the most widespread and versatile pavement for both city streets and early automobile highways prior to the introduction of synthetic asphalt in the 1920s due to its combination of durability, smoothness and being waterproof (figure 12). Unlike all previous pavement types, vitrified brick was industrially produced in brick-making factories, which nonetheless required extensive human labor to collect the clay, form it into molds, place the clay into and remove it from ovens and stack for shipment. Its introduction coincided with the rising popularity of bicycles, whose promoters launched the Better Roads Movement to advocate for smoother pavement, which helped spread the use of vitrified brick by the end of the century.

The Labor of Street Paving

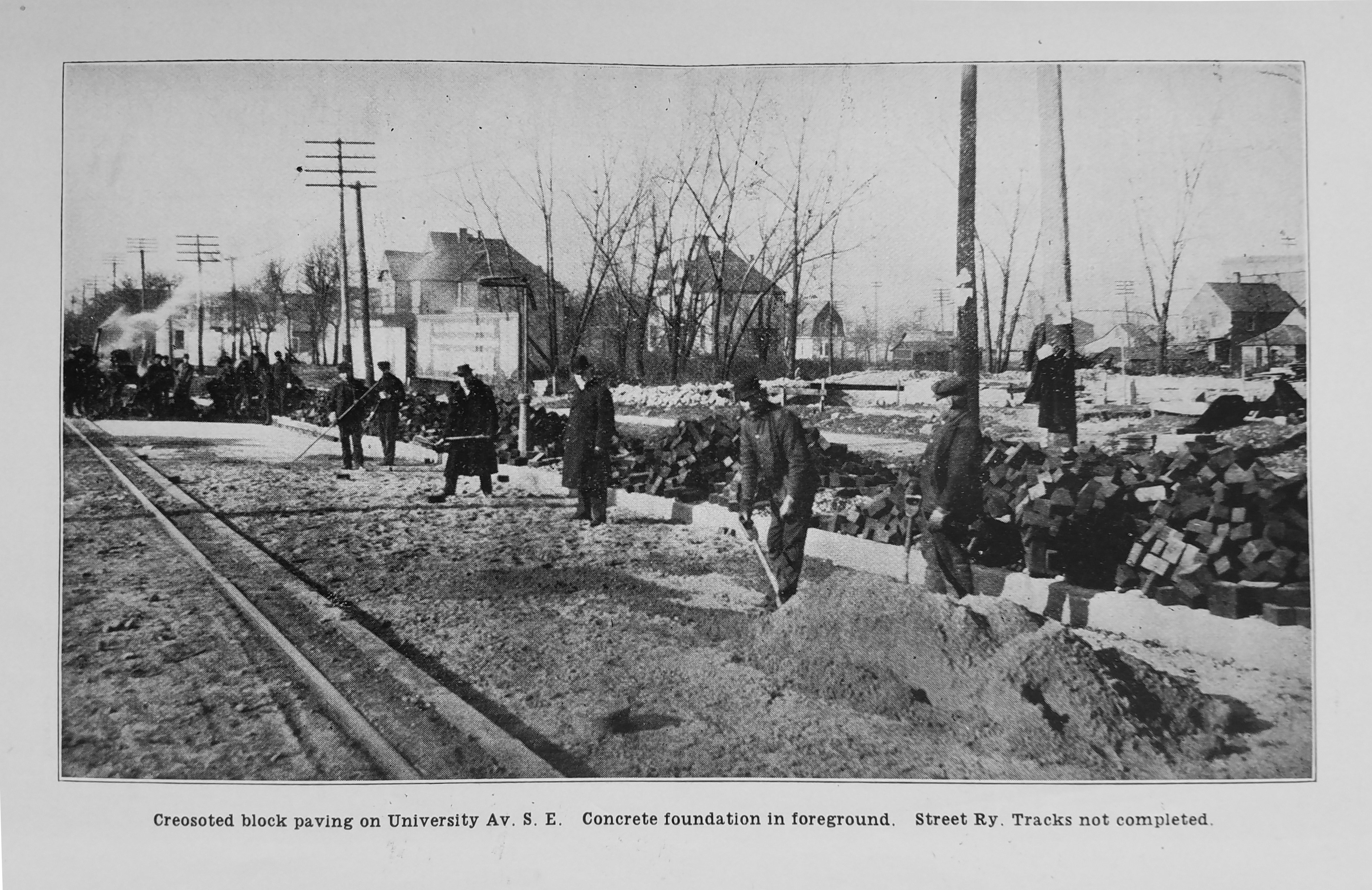

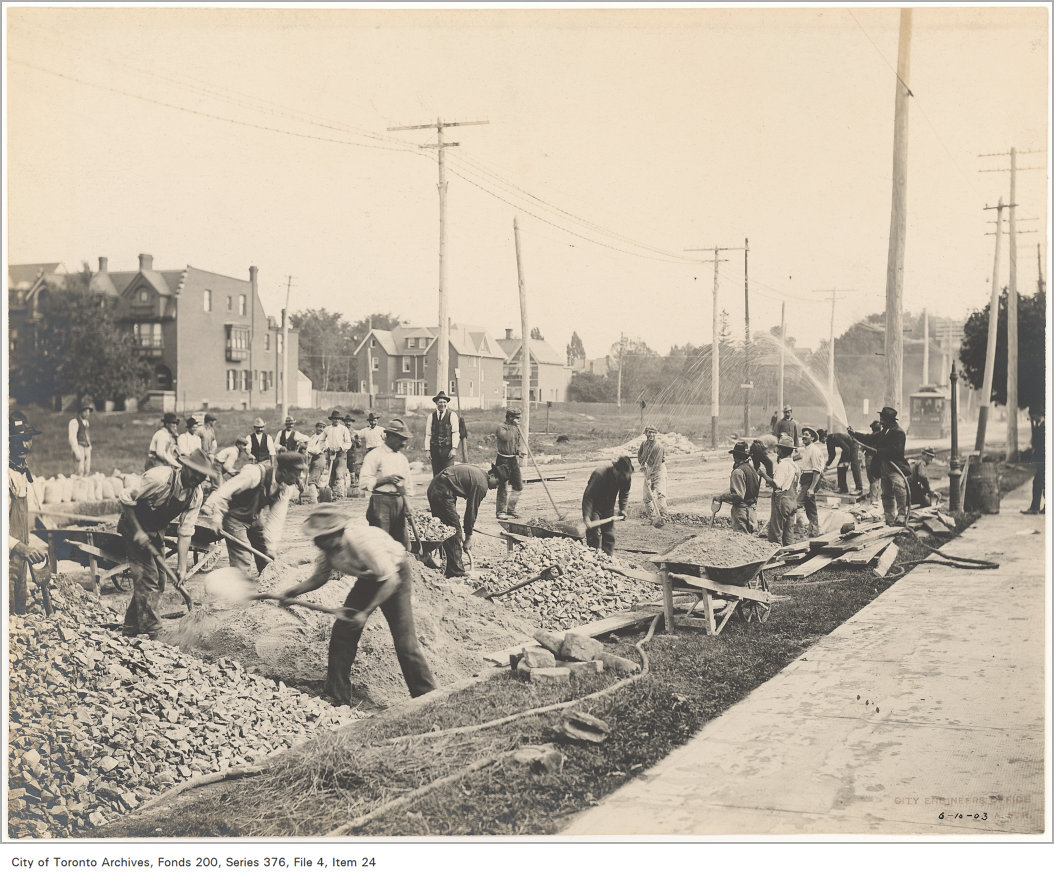

The labor-intensive work of installing block or brick pavements was the public face of the whole pavement production cycle. Municipal engineering or public works department annual reports, as well as pavement manuals, frequently included images of large crews of workers, a vivid testament to the significant financial and human investment permanent pavements represented. The ethnicity of the anonymous laborers varied, with crews of all African Americans (though usually under the supervision of a white foreman) being very common (figure 13). Yet, even in the era of Jim Crow with racial segregation, whites and blacks appear working alongside each other (figure 14). Minneapolis documented both mixed crews and all-white crews, including this 1907 view depicting workers installing pavement in decidedly cold weather, to judge by their heavy coats (figure 15). In Toronto, a range of ethnicities and an equal diversity of hat styles can be seen in the workers laying gravel pavement, likely macadam, on Bloor Street in 1903 (figure 16).

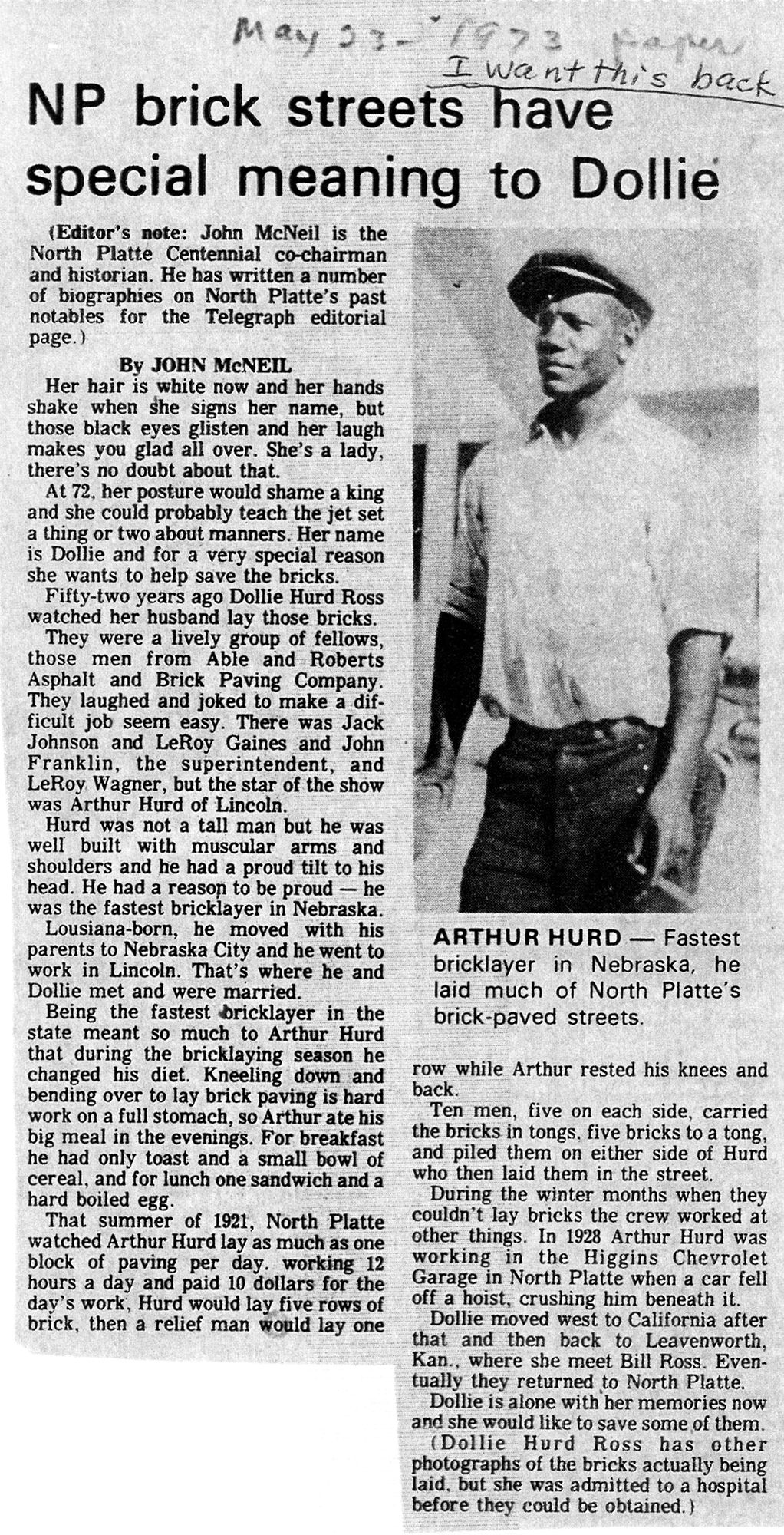

While most manual laborers documented in photos of paving projects were anonymous, occasionally a worker was so exceptional that he received acclaim and individual recognition. Arthur Hurd, a native of Louisiana, moved to Nebraska the early 1920s and quickly distinguished himself as “the fastest bricklayer in the state” (figure 17).[8] To facilitate his bricklaying, “Ten men, five on each side, carried the bricks in tongs, five bricks to a tong, and piled them on either side of Hurd who laid them in the street.”[9] In an interview with his widow, Dollie, in 1973, journalist John McNeil learned that “Being the fastest bricklayer in the state meant so much to Arthur Hurd that during the bricklaying season he changed his diet. Kneeling down and bending over to lay brick paving is hard work on a full stomach, so Arthur ate his big meal in the evenings. For breakfast he had only toast and a small bowl of cereal, and for lunch one sandwich and a hard-boiled egg.”[10]

Likely the most famous American street brick layer of all time was James Garfield Brown, more commonly known as “Indian Jim.” A Native American born in the 1880s on the Oneida Reservation in central New York state, “Indian Jim” Brown (figures 18 and 19) garnered notable press attention during his lifetime and commemoration with a marker and a documentary film after his death. Already considered a “champion bricksetter,” he participated in a head-to-head competition in Olathe, Kansas, on September 12, 1925, against Frank Hoffman of Eldorado, Kansas, to help complete the Kansas City Road. Press coverage reported that “The work of the Indian, who was a discovery of The [Kansas City] Star, was a demonstration that brick-setting may be made an art, not a drudgery. When Indian Jim stretched up from his completed task to hear the cheers of the crowd in his ears, he knew he had been working.”[11] Indian Jim set 46,644 bricks, 1,755 more than Hoffman, in six hours and 45 minutes. According to a monument in Olathe commemorating the day’s events, Senator Charles Curtis, Kansas Governor Ben Paulen and prominent local citizens laid ceremonial bricks as well.

|

|

No matter where he worked, Indian Jim attracted attention. Two years later, in Texas, the Pampa Daily News ran articles on him, including a “Paving Edition” of their paper on November 13, 1927, which extolled his prowess as the “world’s champion bricklayer” able to lay three bricks per second![12] In 1937, a WPA publicity film, “A Better Illinois,” documented an unnamed worker rapidly setting bricks from short stacked piles who may in fact be Indian Jim, with the narrator noting “one of the men engaged in this project is said to be the champion bricklayer of the world; at least he gives the younger hands something to think about” (figure 20). The filmmaker clearly had fun documenting his unusual expertise, speeding up the footage while the narrator wryly intones “this is about how he looks to the greenhorns.” By 1939 his reputation merited inclusion in a Ripley’s Believe or Not cartoon that appeared in newspapers around the country. The cartoon proclaimed “Indian Jim Brown – Full blood Oneida Indian – Lays 58,000 bricks a day – 207 tons. This is his daily average. He challenges any man” (figure 21).[13] His reputation lives on: a marker erected in 2007 in Olathe commemorates Brown’s achievement in the completion of the Kansas City Road;[14] and in 2011, filmmaker Gregory Sheffer cast the actor Raw Leiba to portray Indian Jim in a documentary short film called “The Bricklayer: Indian Jim and the Kansas City Olathe Highway,” part of a documentary series called “Olathe – The City Beautiful” that premiered at the AMC Kansas City Filmfest in April 2011; out of a total of 135 films it won first place in its division for “Best Heartland Documentary Short film.”[15]

|

|

|

Cleaning Streets

Human hands also played a critical role in keeping streets clean. New, permanent street pavements were seen as critical to the progress and health of a modern city, but so too was street cleaning. At a time when horses and other draft animals still filled the streets and regular residential garbage collection did not yet exist, trash, animal urine and excrement, and even dead animals could quickly make newly paved streets objectionable, if not a health hazard. Recognition of the human labor involved in street cleaning appears in a unique graphic using broom sizes to represent the amount of labor required based on the relative cost of cleaning different kinds of pavement in New York (figure 22). No city took greater pride in their street cleaning crews than Detroit, which introduced its highly influential “White Wings Brigade” in 1897 – a force of fifty white men dressed in white suits, each accompanied by a pushcart with a receptacle (figure 23). Leaders in the city’s Public Works department boasted that “Detroit is one of the cleanest of cities. Broad avenues of asphalt and brick and lovely residence streets of cedar block would be given scarcely a passing notice by the visitors were it not for the fact that brush and broom in the hands of expert workers make the streets as scrupulously clean as it is possible for them to be.”[16] The idea immediately proved successful, spawning similar crews within that first year in twenty other cities.[17] By 1902, the brigade had grown to 100 men and continued to be proudly illustrated in the pages of reports.[18] As late as 1923, the city of Los Angeles used the same term “White Wings” to describe their street cleaning workers.[19]

Heritage Work

The arrival of synthetic asphalt in the 1920s gradually curtailed the use of bricks or blocks for new streets, and most old streets disappeared under blacktop before long. Yet, an appreciation for old, hand-made pavements helped some communities keep their old streets intact. For example, streets in Wilmette, Illinois, saw their bricks “Relayed by WPA” (as noted by embedded plaques) – a potentially unique project of that Depression-era government make-work program that involved workers inverting the bricks so that their worn tops were placed face down (figures 13 and 24). One intersection involves obliquely oriented brick rows meeting at a large triangle, displaying a remarkably high level of care and attention to detail. Multiple varied iterations of similar triangular patterns exist around eight of the squares in downtown Savannah, where T-shaped intersections prompted their installation. Early twentieth-century asphalt blocks – a historic paving material that survives in very few cities – form the triangles by having blocks rotated 45 degrees to keep them perpendicular to the turning wheels of two-way traffic. Although movement around the squares is now one-way only (like a round-about), the city maintains the triangles, which require careful attention to detail, as can be seen in the various shades of blocks, with the darker ones being oldest (figure 25).

The rise of the historic preservation movement nationwide for buildings in the 1950s and 60s spread to pavement preservation and restoration in a few cities by the 1970s. The City of Tampa has been a leading city in protecting and maintaining its vitrified brick streets. The restoration of a small section of Morgan Street in 1974 garnered newspaper coverage, which lamented that “although brick-laying probably is a lost art by now, these men chiseled, paced and pounded the bricks with astonishing efficiency.”[20] Like the brick layers of the 1920s, most of the workers are anonymous in such reports, but one street restoration master craftsman, Woodrow Pippin of Tampa, enjoyed a level of recognition that recalls Arthur Hurd and Indian Jim Brown. A 1978 Tampa Times article profiling Pippin characterized him “Like some whiz-bang mathematician sizing a row of five-digit figures… with the eyes of a calculating mathematician.”[21] In Philadelphia, the National Park Service’s restoration of cobblestone pavement on Library Street in the 1970s as part of the Independence Mall project evidently privileged craftsmanship over authenticity, with large pavement stones neatly arranged down the middle of the roadway and much smaller stones laid in elegant sets of arcs along the sides (figure 26), rather than the random irregularity of historic cobblestone pavement, as in Alexandria.

As more cities consider restoring brick and block streets, skilled craftsmen and supportive crews of laborers will be needed once again, a vivid reminder of the central role manual labor has played in the creation of our transportation networks.

Notes

- Regarding New York, see Niko Koppel, “Restoring New York Streets to Their Bumpier Pasts,” The New York Times (July 18, 2010); regarding Philadelphia, see “Historic Street Paving Thematic District” nomination form, Philadelphia Register of Historic Places, 1998, Description section, page 2, accessed June 10, 2018, from https://www.phila.gov/historical/PDF/Historic%20Paving%20Thematic%20District.pdf.

- A marker at the intersection of Princess Street and North Washington Street reads “In the 1790’s many Alexandria streets were paved with cobblestones. According to legend, Hessian soldiers provided the labor to cobble Princess Street.”

- W. M. Gillespie, A manual of the principles and practice of road-making: comprising the location, construction, and improvement of roads (common, macadam, paved, plank, etc.); and railroads (New York: A.S. Barnes & Co., 1848), 216-17.

- “1823 – First American Macadam Road,” The Paintings of Carl Rakeman, U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. Accessed April 25, 2018 from http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/rakeman/1823.htm.

- John W. Alvord, “A Report to the Street Paving Committee of the Commercial Club on The Street Paving Problem of Chicago” (Chicago: R. R. Donnelley & Sons Company, Printers, 1904), exhibit no. 2. Macadam represented 50.1, 30.1 and 28.35 percent of all street surfaces in Boston, New York and St. Louis, respectively.

- Daily Morning News [Savannah], October 25, 1859, p.2, col. 1.

- An early use of this term is “A Noiseless Pavement,” Daily Alta California (September 16, 1876), 1.

- “Downtown streets were paved by ‘fastest bricklayer in the state’,” North Platte Bulletin (Oct. 29, 2010), posted on the Save the Bricks in Downtown North Platte website. Accessed online: http://www.savethebricks.com/2010/11/17/downtown-streets-were-paved-by-fastest-bricklayer-in-the-state/.

- John McNeil, “NP brick streets have special meaning to Dollie,” North Platte Telegraph (May 23, 1973).

- Ibid.

- “Olathe Celebrated a New Brick Road Saturday—and `Indian Jim’ Wins,” The Olathe Mirror (September 17, 1925), 5, reprinted in Pat Davis, “’Indian Jim’s’ victory recalled as K.C. brick road is removed,” The Daily News [Olathe, KS] (October 22, 1971), 6A.

- Mike Cox, Texas Panhandle Tales (History Press Library Editions, 2012).

- Ibid.

- For information on the marker, see The Historical Marker Database, https://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=20270.

- The almost two-minute short film can be viewed online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wyLWNlMXDEU. See also “Olathe Film Series,” Kansas City Area Historic Trains Association website, https://www.kcahta.org/our-history-1/olathe-film-series/.

- “Twenty-fourth Annual Report of the Board of Public Works of the City of Detroit, 1897-8,” in Annual Reports of the Several Municipal Commissions, Boards and Officers of the City of Detroit, for the Year 1897-8 (Detroit: The Richmond & Backus Company, 1898), 48 (Detroit Public Library).

- Ibid., 49.

- “Twenty-Eighth Annual Report of the Board of Public Works of the City of Detroit, 1901-1902,” in Annual Reports of the Several Municipal Commissions, Boards and Officers of the City of Detroit, for the Year 1901-1902 (Detroit: The Richmond & Backus Company, 1903), 60 and accompanying image between pages 57 and 59 (Detroit Public Library).

- John Griffen, “Annual Report of the Engineering Department of the City of Los Angeles, July 1st, 1922, to June 30th, 1923,” 19 (City Archives and Record Center, Los Angeles).

- “Streets of Brick,” The Tampa Tribune (August 16, 1974), 6-Metro. Copy in the “Tampa-Streets / (1800’s – 1970’s)” vertical file, Special Collections, Tampa Public Library.

- Dale Wilson, “Brick laying doesn’t put them on easy street,” The Tampa Times (June 5, 1978), section B Copy in the “Tampa-Streets / (1800’s – 1970’s)” vertical file, Special Collections, Tampa Public Library.

Robin B. Williams, Ph.D., chairs the Architectural History department at the Savannah College of Art and Design. His research focuses on the history of modern architecture and cities, currently focusing on the evolution of street and sidewalk pavement in North America. He is the lead author of Buildings of Savannah (University of Virginia Press, 2016), the inaugural city guide in the Society of Architectural Historians’ Buildings of the United States series.

Return to People-Works: The Labor of Transport.

![Diagram showing relative labor involved in cleaning different types of street pavement in New York. Source: John W. Alvord, 'A Report to the Street Paving Committee of the Commercial Club on The Street Paving Problem of Chicago' [Chicago: R. R. Donnelley & Sons Company, Printers, 1904], exhibit no. 8).](https://t2m.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Williams_figure-22.jpg)