Embedded Economies of Non-Consent: The Chillia Taximen of Mumbai

By Tarini Bedi, University of Illinois-Chicago, USA

Dr. Bedi is Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of Illinois in Chicago, USA. She is also a member of the executive committee for the International Association for the History of Transport, Traffic and Mobility (T2M). This excerpt is part of a book that is an anthropological history and ethnography of Bombay’s taxi-drivers and others connected to the taxi-trade from the late 19th century to the present. The book explores the relationships between those who drive for a living as part of a city’s public transport and the political, domestic, residential, and “intimate” communal workspaces that are created around them over time. A version of this was presented at the 2016 T2M conference in Mexico City. A detailed, article-length version is forthcoming in the journal Modern Asian Studies.

Introduction: Old Workers in a New City

I sat on the floor of taxi-driver Rahim’s house. Rahim limped despondently past the bright curtain that shaded the dark, front room of this two-room house in a small Mumbai settlement on a rainy July evening. With him, a profound sadness floated in to hang heavily over all of us, much heavier than the violent Mumbai monsoon that battered against the tin roof. “Padmini mari gayu” he said softly in Gujarati— “My Padmini has been killed.” “My taxi has been cut into many pieces, but my heart is broken into many more.”

Rahim is from a working-class Muslim community known in Mumbai as chillia. His family had driven taxis in Bombay since the early twentieth century. That evening, Rahim had returned from Mumbai’s Motor Vehicles Department, the state’s main licensing and regulatory body. At his annual visit to get his taxi’s license renewed, he was forewarned that it no longer complied with new regulations on age and would need to be handed over to the state to be destroyed. Rahim’s youngest son, Syed drove the same car for the evening shift and his brother-in-law Bilal drove the car on Fridays when others went to prayers at the mosque. This shared car had a long and hard-working relationship to Mumbai’s roads, as did the men who had driven it. Syed and Bilal sat next to Rahim and complained in anger: “All these years the RTO (Regional Transport Office) officials took our bribes and gave a passing certificate; now all of a sudden they are trying to enforce the law? What was the real age of this car? What is age anyway? Is it the body of the car the inside of it? We have put in a new engine, a new taillight, new brakes, and a new CNG (compressed natural gas) tank. But they have decided it’s too old, only because it looks old, and has no place in the new Mumbai; they want us to either buy new cars or give up our family business and join a fleet-taxi company. Where will we get the money to buy a new car? After being a public servant my whole life, who wants to become a ghulam (slave) of the private sector? What happens to workers?”

To ensure that Rahim’s old vehicle would never again benefit from upgrades or repair that had marked its life, three low-level employees of the state government violently yanked the doors off the car before a small crane came down to crumple its roof. Rahim, holding his head said softly: “My family, we were Bambai’s original taxi-drivers but there is no place for anything original or joona (old). The police, the RTO, this sarkar (government), and even our own union people have decided that only what is modern can be on the roads, never the old. We are old taxi-drivers and our taxis are old cars. There is no place for us in this new Bombay.”

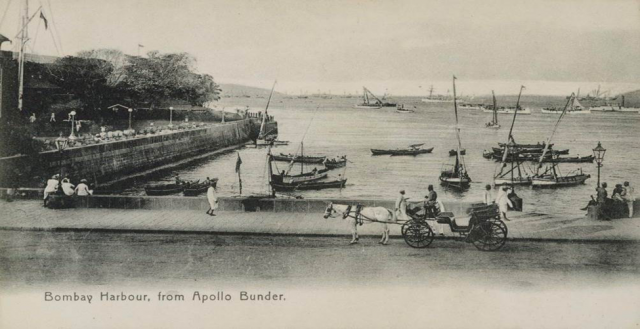

Rahim, Syed, and Bilal drew an important arc between the modern history of a particular mode of urban transport and the labouring history of those who drive, move, and fix it. Their position as hereditary drivers in a changing city is lens through which I explore several questions about transport labour in cities of the non-Western world. Rahim’s community of hereditary drivers, the chillia, has driven taxis in Bombay since the early twentieth century and continues in contemporary Mumbai’s taxi-trade. Their working lives have been closely connected to Bombay’s political, cultural, and economic history. Rahim for example, drove a Premier Padmini kaalipeeli (black and yellow) taxi, one of the first automobiles to be mass-produced in India, and icon of postcolonial Bombay’s taxi-trade, for almost thirty-five years. His father and grandfather also drove taxis for over five decades. His great-grandfather was the first to migrate to the city as a teenager. He followed his maternal uncles to colonial Bombay in the early twentieth century to drive a horse-drawn hackney, very similar to those driven in England at the time (see image 2).

Through a focus on the chillia, and networks of work that emerged around them, I underscore the importance of looking at urban transport not simply as material or mobile system but as social and cultural assemblages. It particularly illuminates how the chillia taxi-trade and circuits of obligation and reciprocity, experienced by this community of hereditary drivers encompass other forms of mobility-related work. These related social circuits of mechanics, car-wash operators, and smugglers of spare parts that emerged out of the needs of the chillia taxi-trade are all part of this embedded economy and deeply intertwined with the history of chillia migration through the 20th century, their labour subjectivities, and relationships of their motoring labour to the city. This resonates with scholarship on transport workers in other parts of the non-western world that argues that this category of labour is particularly useful in interrogating articulations between local and global forms of capital. It is also a useful site from which to examine how local livelihoods both shape and counter these articulations.

I am concerned with four dimensions of transport labour. First, I am concerned with the connection between the work of hereditary motoring and the reconfiguration and constitution of new communal identities in contexts of urban labour migration. Second, I am interested in the ways that motoring labour practices are embedded in broader social and cultural space. In South Asia, mobile labour has created and shaped locales that receive them. Chillia drivers are an interesting case because they are mobile workers but their social lives are uncharacteristically emplaced compared to other mobile transport workers. By locating the study ethnographically in one residential neighborhood of chillia drivers, mechanics, car-wash operators, and taxi-leasers in Northern Mumbai called Pathanwadi, I approach labour practices as they are embedded in both mobile and immobile urban cultural and social space.

Thirdly, given that chillia have continued in the trade for over a hundred years, circuits of work and labour surrounding their trade are useful sites at which to interrogate intersections between political and cultural shifts in the city and changing conditions of work in contemporary contexts of globalizing capital. I entered this community in 2010 at the height of debates over the future of the taxi-trade. Drivers like Rahim faced intersecting forms of destruction—of their taxis, of labour structures of their trade and with this of circuits of reciprocity that characterized the trade for over a century. A large part of this destruction began in 2006, when Mumbai’s city and state government introduced what became known as “taxi-modernization.” The initial call was for new cars to replace older kaalipeelis. This was encouraged by car-manufacturers tapping into the taxi market. This was accompanied by encouragement of investment in taxi-fleets.

Under pressure from urban elite groups and corporate investors in taxi-fleets, the state government’s calls to “modernize” cars, and regulate and rationalize roads expanded to efforts to formalize and manage motoring labour. By encouraging drivers to learn English, receive etiquette training, and wear standardized uniforms, it disciplined motoring labour to conform to aesthetic dimensions of an ordered city. It also introduced new pollution control and permitting mandates that steered older cars into retirement. Veteran drivers had three choices: to buy new cars in order to keep driving, to give up their taxi-permits to the state and leave the trade, or to sell their permits to a corporate fleet who would employ them. Each of these choices had impacts on embedded structures of labour in the trade. This engendered vitriolic debates over the place of taxis and drivers in the “global” city of Mumbai. Additionally, for chillia drivers who always pooled resources to purchase vehicles to avoid Islamic religious restrictions against loans and interest, the purchase of new cars was doubly complicated.

Motoring, Migration and Working-Class Identifications: Emergence of the Category of “Chillia”

Chillia identify as Sunni Muslims of the Momin caste. In Gujarat the bulk of this community live in and around the area of Palanpur, which was a former princely state of India. Prominent families, particularly princely families kept stables as marks of their cosmopolitanism and upper-class status. The stables were important places of employment for Muslim labour otherwise employed in marginal farming and petty trades. Many of those employed in the stables took their knowledge of horses with them and followed other family members into Bombay’s transport trade as drivers of horse-drawn Victoria taxis. By around 1911, Victoria taxis began to share the road with motorized taxis. Finally, Victorias disappeared and many Palanpuri carriage-drivers moved to the motorized taxi-trade together.

The needs of the trade in colonial Bombay manifested itself spatially. Palanpuri drivers settled residentially in and around spaces where they could park their Victorias and harness horses. Care and grooming of horses required several members of the community. When drivers moved to motorized cars, many families responsible for servicing carriages and grooming horses started small spare-parts businesses, tire, and mechanic shops. This meant that residential communities made up entirely of taxi-labour emerged. These close spatial arrangements have persisted throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Pathanwadi, where I conduct my ethnographic research is one such community.

The ethnic identification as chillia was also a discursive strategy of distancing from other taxi-driving communities who also organized their working lives around ethnic and religious connections. For example, by the early post-colonial period three minority communities dominated Bombay’s taxi-trade: Palanpuri Momins, Konkani Christians from Mangalore, and the Sikhs. By the 1960s, most Sikh drivers moved into heavy motoring like truck driving. Due to different structures of migration, and significantly higher literacy than others in the taxi-trade, Mangaloreans gave up on motoring and moved into white-collar occupations. However, Mangloreans continued to be associated with the labour movement in the city and with the organization of taxi labour. The primary association responsible for negotiations on behalf of taxi-drivers. Almost all the top leadership of the biggest taxi union in the city, the Mumbai Taximen’s Union continue to be Mangalorean Christians.

Since Mangaloreans are not drivers anymore but still hold a prominent place as representative voices of the taxi-trade makes for suspicion on the part of chillia. It has intensified local, ethnic alliances in chillia neighbourhoods and these alliances are often at odds with actions of union and labour leaders. The chillia feel that the union is colluding with the state and against interests of observant Muslims who cannot take loans for the purchase of new cars as easily as others can without violating the Islamic rules again riba or interest. As Yusuf says, “Dealing with any kind of interest payment is against our religion. If the government asks for new cars, what they are really doing is pushing Muslims like me out of the trade” Arguably, Yusuf voices an important debate swirling around taxi stands in this community. On one hand, this could be seen as a debate amongst pious Muslims on how to make empowering choices for themselves in the project of globalization and on how to remain significant urban actors on their own terms. However, on the other hand, it is also important to see these oppositional claims expressed through religious rules and cooperative economic practices in broader economic terms. In this sense, opposition is a broader strategy of inhabiting entrenched practices of work by insisting on spreading the measures of financial risk across the community. This allows everyone in the community greater capacity to reposition themselves in relation to future economic opportunities and other economic actors. These are what urbanists like AbdouMaliq Simone calls “maneuvers,”actions by people in difficult urban environments across the world to steer economic transactions into opportunities for inclusion in other, future but undefined opportunities that are assumed to be better than what is offered in the present. The capacity to “maneuver” has been vital to why chillia continue to drive on their own terms today.

Finally, customary, ethnic boundaries are connected to subjectivities produced out of a sense of enduring connections to urban mobility and early automobility in the city. For most chillia, this connection is an important part of the community’s place in Bombay’s urban modernity. In the early days of taxi-motorization, several models of British and American cars entered the taxi market. Chillia drivers frequently narrated family histories of motoring through the materialities of these different models of cars. In 1956, the Indian company Premier Auto tied up with Italian car-maker Fiat to manufacture the Fiat 1100 Millicento out of a suburban Bombay plant. This was one of the first models of cars to be mass-produced in India. It was marketed as a luxury car. By the 1970s, Premier automobiles started producing the Indian brand Premier Padmini. Many drivers remember that production was heavily regulated; they had to get on waitlists to get one. This amplified its aspirational aspects. Successful purchase of the Padmini consolidated drivers’ standing in the community. Chillia drivers purchased Padminis either through pooling resources of extended families or through special loans from the Bombay Mercantile Bank, a Muslim-owned cooperative bank that provided loans with no interest. This model of car has become the iconic kaalipeeli that many chillia still drive. For chillia drivers, history of its acquisition, the acceptance in the community that the purchase conformed to Islamic rules against interest, and embeddedness of this car in daily lives inflects their experiences as urban transporters. Padminis were manufactured until the plant closed in 2000. By 2006, the city began its taxi-modernization project that mandated that all Premier Padminis, more than twenty years old must be retired. This produced heated debates and organized efforts to stall this mandate among chillia in Pathanwadi.

This focus on new, modern cars was accompanied by other disciplinary techniques focused broadly on “conduct.” The most important were those associated with reforming the labouring body. Fleet taxi-drivers had to wear standardized uniforms, learn English and become proficient with the use of technologies most closely associated with modern mobility—Global Positional Systems (GPS). The use of khaki uniforms for taxi drivers had long been a way to distinguish owner-drivers (who wore plain clothes) from leasee drivers who wore uniforms. For most of Bombay’s postcolonial period, taxi-drivers associated uniforms as marks of bondage to an employer and the white or plain clothes with autonomy and a visible symbol of ownership of the means of mobility. Therefore, the mandate for all drivers to wear uniforms disrupted customary distinctions between owners and lessee drivers and the embodied symbols associated with social mobility in the taxi-trade. The chillia, as owner-drivers had always worn clothing that marked them as chillia: distinctive, long white shirts, white pyjamas, and a prayer cap or topi. Therefore, the requirement to discard these markers of identity was seen as another form of control over chillia identity.]

Conclusions: Chillia and Capacities for Non-Consent

In conclusion: Islamic piety, entrepreneurship, urbanization, and hereditary knowledge of the car have all been important in shaping motoring subjectivities and political and cultural claims over time. This capacity to make collective claims makes chillia distinct from other workers in the non-industrial sector and indeed from many others in the more precarious transport sectors. This is what allowed them to continue to shape Mumbai’s taxi-trade from below through various strategies of non-consent.

So far, the chillia have resisted joining the fleet-taxi companies even as they have been subject, as Rahim was, to various forms of destruction. Indeed, by 2016, ten years after they were all supposed to be absorbed into the corporate-owned fleets chillia drivers continued to drive on their own terms. In 2006 when the fleet taxi model was introduced and when the debate over the “age” of cars began, the city’s planners and middle-classes were convinced that transformation was within reach. Fleets have had some success recruiting recent migrants as employee-drivers. They have also tried to draw on some of the practices of the existing taxi-trade, i.e. trying to draw on customary notions of social cohesion and friendship among those they recruit. However, they have had little success with chillia drivers. Arguably, this is because the embedded economy of the chillia trade operated not simply as a social network but as a vital arbiter in the allocation of human, cultural and physical resources. Chillia motoring practices do not map onto the dominant rules of anti-social markets. Their hereditary connection to the trade has instead allowed them the capacity to sustain an “ecology of practices”[1]over time that do not adhere to dominant prescriptions for a viable future of the taxi-trade.

[1] AbdouMaliq Simone, “Relational Infrastructures in Postcolonial Worlds,” in Infrastructural Lives: Politics, Experience and the Urban Fabric, ed. Stephen Graham and Colin McFarlane (London, UK: Routledge, 2014); Isabelle Stengers, Cosmopolitics 1 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010).

References

Simone, AbdouMaliq. “Relational Infrastructures in Postcolonial Worlds.” In Infrastructural Lives: Politics, Experience and the Urban Fabric, edited by Stephen G