African Automobility: Mammy Trucks In Twentieth-Century Ghana

Jennifer Hart, Wayne State University

Table of Contents

- Body work

- Mammy trucks

- Training drivers

- Testing officers

- Local transport cultures

- “Modern men”

- Trotro – a “proper” car

- Urbanization and technological change

- New models, old business

- Economic crisis and creativity

- Conclusion

- References

Introduction

This exhibit uses a technological object – the “mammy truck” – as a framework to explore the various forms of labor that shaped a mobility system in twentieth-century Ghana. Motor transportation is a frequent topic of conversation on the streets of contemporary African metropolises and rural villages. Passengers and politicians bemoan the frequent traffic jams, dangerous road conditions, and accidents that plague their communities – conditions that are often assumed to be timeless. The heated public commentary and persistent attempts to reform the transport industry implicitly acknowledge the importance of motor transportation across the continent even as they dismiss these transport networks as part of the “informal economy.”

Yet the negativity of the present belies a much more complex history of entrepreneurial innovation, creative adaptation, and economic independence. Motor transport technologies arrived on the continent through networks of imperial trade, and colonial officials frequently viewed motor transportation as a symbol of European superiority that would inspire awe in colonial subjects. However, Africans who embraced the social and economic possibilities of motor transportation in colonies like the Gold Coast often did so on their own terms. Africans built infrastructure, adapted technology, and constructed mobility networks that simultaneously built on older systems of circulation and exchange and responded to the unique possibilities and challenges of the early twentieth century. Like colonial administrations elsewhere on the continent, British officials in the Gold Coast sought to restrict African mobility and access to technology. Their efforts were stymied by the colony’s class of prosperous African farmers and traders, who invested their profits in the new technology as a way to preserve their economic autonomy, facilitate social mobility, and control terms of trade.

The cosmopolitanism and economic dynamism of early twentieth-century Gold Coast society was, in many ways, embodied in the mammy truck. The mammy truck adapted older networks of trade and cultures of movement associated with the head carriers and cask rollers who had transported cash crops like palm nuts and cocoa from interior farms to coastal ports as part of long-distance trade networks in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The vehicle itself also required various levels of assembly – assembling the metal chassis, building the wooden body, painting the vehicle. This act of assemblage, which drew on both local and global technological skill, expertise, and labor, cast the mammy truck as a sort of hybrid vehicle. African entrepreneurs like farmers and traders invested in these vehicles soon after their introduction in the early years of the twentieth century, adapting the vehicles to reflect the needs of owners and passengers. As the name “mammy truck” implies, these vehicles were closely associated with market traders – predominantly women – who utilized the speed, convenience, and autonomy of the truck to expand their control over local and regional trade. Vehicle owners soon saw the economic potential of automobility – hiring out their vehicles to carry a wide range of goods and/or passengers within and between rural and urban areas, within and beyond the boundaries of the British colony of the Gold Coast. By the 1930s, Africans from all parts of Gold Coast society utilized the mammy truck to move.

Vehicle owners and drivers continued to adapt as social, political, and economic conditions changed. By the 1960s, drivers were using wooden-sided vehicles to transport passengers in the capital city, Accra. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, persistent economic crisis meant that drivers and vehicle owners had to employ creative methods to keep their vehicles on the road even as they faced increasing governmental and public criticism. Market liberalization brought a flood of second-hand vans and buses into the country in the 1990s, which drivers quickly adapted to serve the needs of the passenger-public. The adaptability of transport workers in the face of significant economic change is a testament to their economic creativity. However, these same economic changes also drove increasing numbers of young men into the motor transport industry, flooding the labor market and undermining systems of training and professionalization that had long defined drivers as respectable men of status and skill. Economic change also meant that new kinds of vehicles appeared on the road, as mammy trucks and later trotros competed with municipal and omnibus systems, taxis, and articulated trucks for control over the motor transport system.

The images, sound, and video in this digital exhibit highlight the different forms of labor and technology at the center of Ghana’s transport industry, as well as the changing cultural meaning attached to drivers and their vehicles over the course of the twentieth century. It concentrates, in particular, on dominant forms of mass transportation like the mammy truck and the trotro. These histories are critical to our understanding of African social, cultural, and economic history. The movement of populations and the processes of urbanization, political mobilization, and economic and cultural exchange that their mobility made possible shaped much of the history of the twentieth century in countries like Ghana. However, the experiences of Ghanaian automobile workers also provide a powerful challenge to dominant narratives about labor, technology and mobility within and beyond Africa. In contrast to western narratives of automobility, dominated by the American culture of the open road and the family car, African automobility in the Gold Coast/Ghana was organized around cultures and practices of public transportation that sought to connect communities, create economic opportunities, and decrease distance. The history of motor transportation in Ghana reminds us that while technologies might move through global networks they do not have universal meaning. Local transport workers – fabricators, mechanics, drivers, apprentices – and their passengers gave motor transport technology meaning through use.

Body Work

The first motor vehicles were imported into the Gold Coast Colony at the turn of the twentieth century. Government officials and coastal elites often used early vehicles as part of public displays of wealth and status. However, the poor conditions of most early roads made it nearly impossible to use these vehicles. The introduction of more durable vehicles with higher clearance, sturdier frames, and interchangeable parts – qualities most closely associated with the Model T Ford, which began production in 1908 – opened up new possibilities. British companies like Bedford and Austin dominated the early market to such an extent that “Bedford” became a widely-embraced nickname for these vehicles. Import restrictions were relaxed slightly in the context of World War I to allow for the import of highly durable and popular Ford trucks. Dockworkers transported disassembled vehicles from cargo ships on surfboats to sheds along the coast in cities like Accra. There, mechanics assembled the engine and chassis, carpenters constructed the wooden body, and artists painted the vehicle body and its colorful inscriptions.

Mammy Trucks

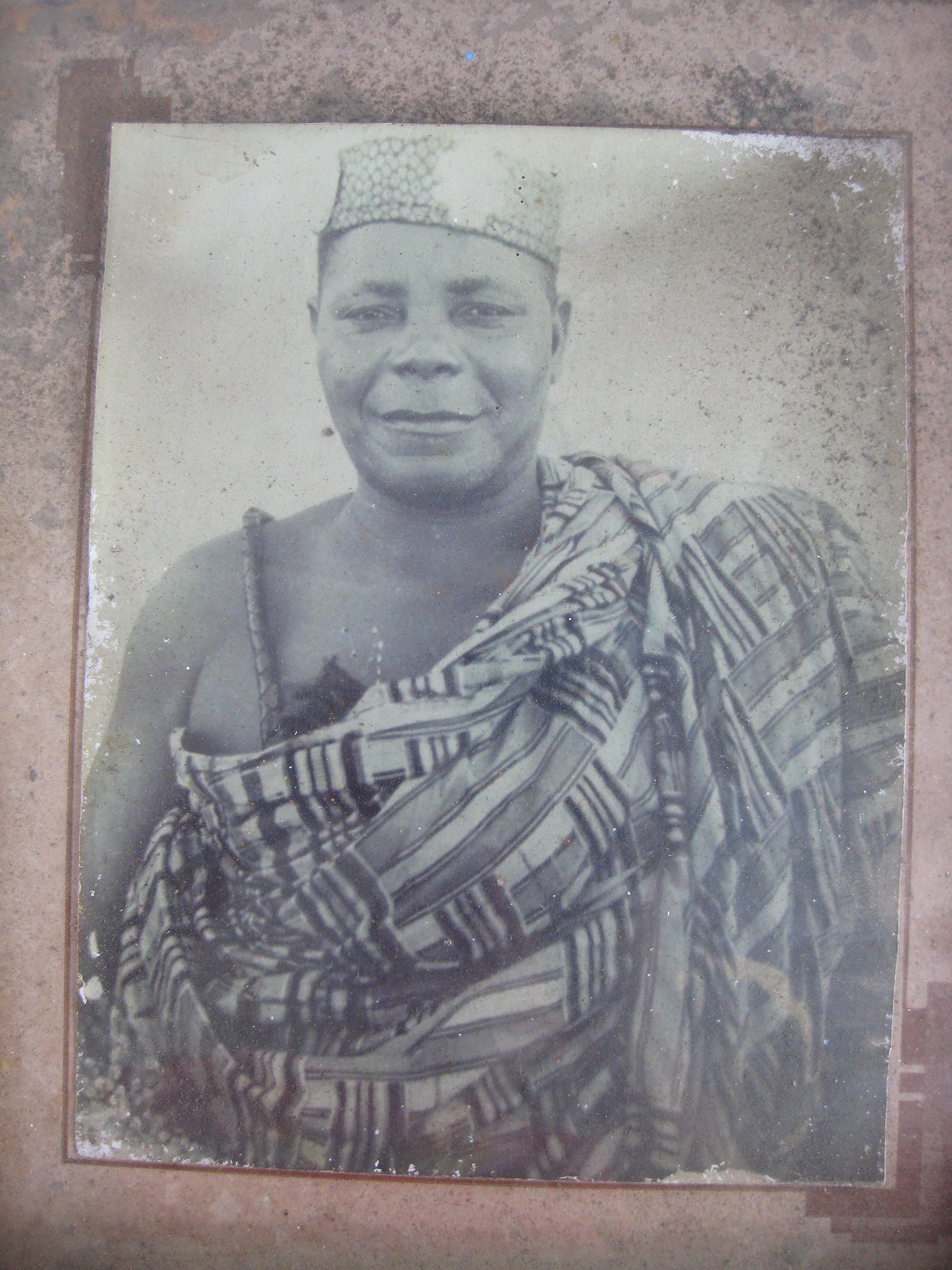

Early vehicles were used primarily for cargo transport. Farmers and traders used the wooden-sided lorries to transport produce from rural production zones to regional markets and coastal ports. These sorts of practices were extensions of local cultures of entrepreneurialism and commerce, but they were also expressions of resistance. In embracing the motor vehicle and financially investing in motor transport technology, African entrepreneurs sought to maximize their profits and secure some control over export-oriented cash crop economies. The British colonial government invested heavily in railways in the early twentieth century. Built primarily in regions that were rich in agricultural and mineral products, railways were supposed to centralize resource extraction, increasing European authority over almost all parts of the export-oriented trade sector. African farmers and traders invested their profits in motor vehicles and local communities constructed their own roads in order to bypass these systems and preserve their role in long-standing local and long-distance trading networks. The names associated with these vehicles reflected the ways that they were used and the meanings ascribed to them in local social and economic networks. Among members of the general public, these vehicles were often known as “mammy trucks” (also “mammy wagons” or “mammy lorries”) – a reference to the market women (e.g. “Makola mammies”) who frequently used the vehicles to trade. Other terms like watonkyene (“you have gone to get salt”) also referenced the long-distance trade connections through which these traders exchanged salt for tomatoes and fish. Still others (“boneshaker,” for example) referenced the uncomfortable conditions of the wooden seats on rough, unforgiving rural roads.

Testing officers

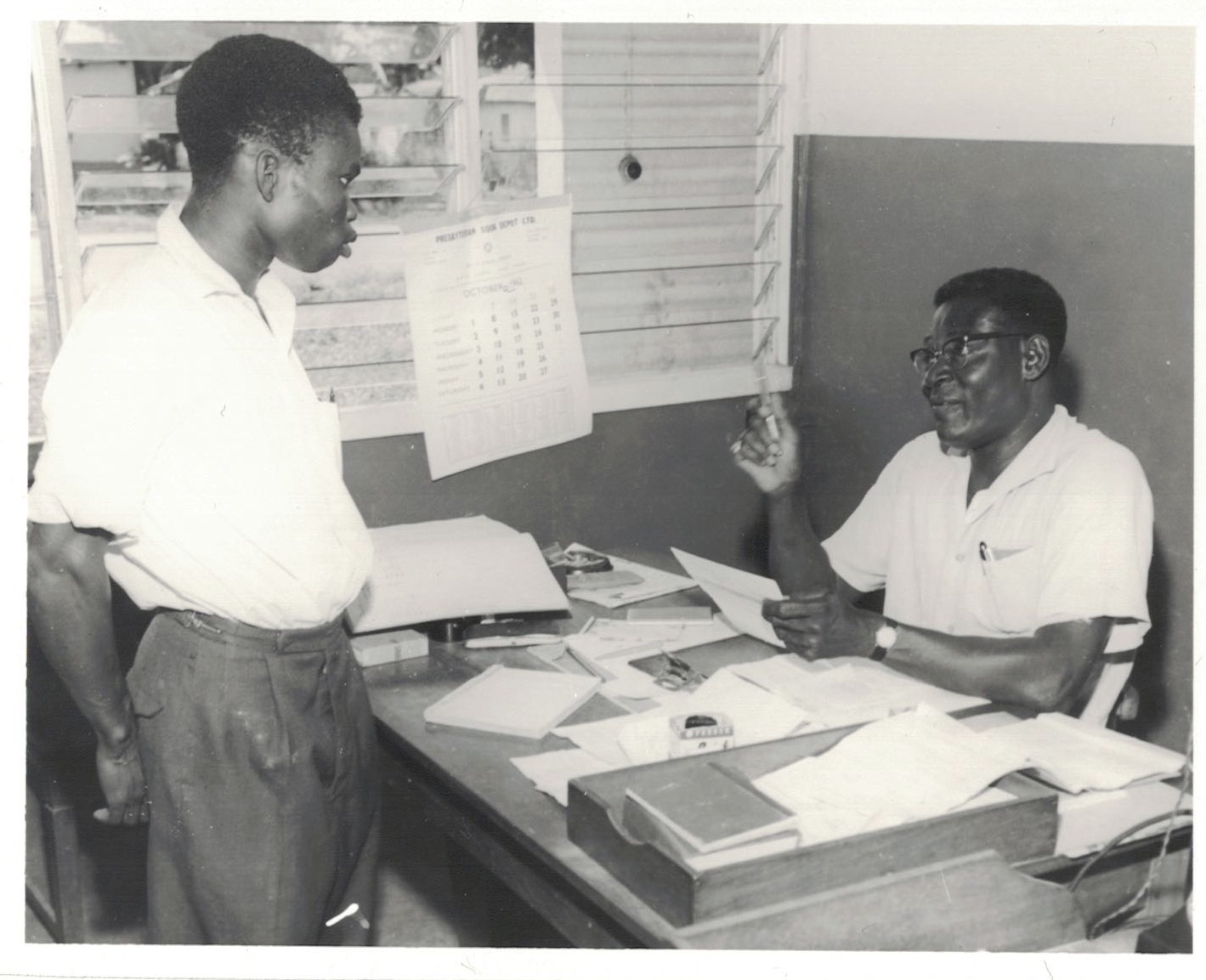

Master drivers determined when mates were sufficiently qualified to go for a license test, which involved assessments of both practical skill and temperament. Many drivers have vivid memories of their examinations. Masters would take them to a hill outside of town, park, and shut off the vehicle. Mates were instructed to place a piece of chalk behind the back tire, start the vehicle, and move forward up the hill without breaking the chalk. Mates who were successful were allowed to go to the licensing office for a formal test. Young men often saved up pocket money to pay the testing fees. Early drivers were assessed only on the technical knowledge associated with the vehicle itself. However, by 1934, new forms of regulation also required drivers to pass literacy tests and meet other standards that defined “the type of man suited to be a driver,” engendering new debates about expertise and professionalism. In the context of colonialism, these debates often took on paternalistic and racialized tones, as British colonial officials sought to regulate African engagements with technology and mobility. After independence, debates about driver training and licensing were often intimately connected to concerns over accidents and debates about public safety and the public good. Regardless, the licensing test itself was considered a rite of passage for drivers, who often could still easily recall the names of their testing officers and the details of their examination decades later.

Local transport cultures

Increasing government regulation in the mid-1930s prompted drivers to organize themselves into unions, which could help define standards of professionalization and enable drivers to better negotiate with colonial government officials over regulatory standards, fees, and fares. Drivers’ unions adapted the British trade union tradition, relying on local models of chieftaincy and economic organization to create meaningful models of authority and solidarity. All early unions had a “chief driver,” whose manner of dress and ceremony often echoed the cultures and practices of local political authorities. However, particularly in Ga communities like La and Teshie, where there were large concentrations of drivers and driving families, these unions formed tight-knit social organizations with unique forms of cultural expression. Unions in La and Teshie not only had a Chief Driver, but they also had elaborate swearing-in ceremonies and a “linguist” (spokesman of the chief) who carried a wooden staff topped with a mammy truck. In La, drivers created a unique musical form, which built on work cultures among long-distance drivers who would honk horns and beat tire rims to chase away animals while repairing their vehicles in rural areas. La drivers adapted these instruments to play local musical styles, including highlife music, in what they refer to as “por por” music (mimicking the sound of a horn).

Modern men

Drivers also cultivated cultures of cool associated with the cosmopolitanism of their mobile work. By the 1950s and 1960s, drivers were highly respected as “modern men,” defined by their steady incomes, mobile lifestyles, and standards of professionalism and skill. Popular highlife songs of the period like the Kakaiku Band’s “Driver Ni na Meware no” talked about how women “want to marry a driver.” Drivers and passengers alike argued that the steady income of drivers made them desirable mates. Daily income and flexible work meant that the family would always get their “daily bread.” However, drivers also used that income to purchase imported goods, build houses, dress in fashionable clothing, and send their children to school. For many of these men who did not have access to formal education and the cultural and economic resources of elite colonial society, driving represented an alternative path to respectability. The worldliness attached to physical mobility facilitated a broader socioeconomic mobility for many drivers, their families, and their passengers. In the process, these mobile workers cultivated a culture of distinctively African automobility. These processes are embodied in scenes from the classic film The Boy Kumasenu, produced by the Gold Coast Film Unit in 1952. In the clip below, a young man grapples with the desire to know a broader world and the excitement of the city – something he encountered directly by observing the lorry drivers who spent time in the village store where he worked.

Trotro – a “proper” car

As British colonial rule came to an end, drivers frequently used their positions to further the nationalist cause, participating in strike actions as part of Kwame Nkrumah’s “Positive Action” campaign and championing decolonization and political participation. This explicitly political action echoed the role of the mammy truck as a symbol of economic autonomy and ingenuity in the new nation. By the 1960s, some vehicle owners in the capital city, Accra, began using the mammy truck in a new way: to transport passengers around the city. Known as “trotros” – after the Ga word for three, a reference to the original fare – these vehicles had their roots in the practices of mammy truck drivers who British officials condemned for operating “pirate passenger lorries” in the 1930s and 1940s. Trotros became cultural icons, closely associated with the market women who frequently used them in their daily work, but also facilitating the movement of a wide swath of other African residents in the cultural, commercial, and political capital. Passengers climbed in through the open sides of the wooden-bodied vehicle, sitting close together on wooden benches. The tarpaulin that was frequently rolled up on the sides of the vehicle provided protection for passengers during the rainy season.

Urbanization and technological change

Demonstrated in the two images below (taken of the same lorry park, from nearly the same angle), between the 1960s and the 1970s, competition within the industry and the technology available to drivers changed significantly. Some of that change reflected the rapid urbanization in cities like Accra after independence. A city that had 133,192 people in 1948 had more than doubled to 337,828 by 1960. Independence also brought a relaxation of import controls and an expansion of opportunities available to African urban residents. Drivers responded to this demand, expanding passenger services in the city and developing new routes within emerging neighborhoods and suburbs. Urbanization increased demand for transportation, which enabled drivers to charge higher fares and guaranteed regular business. Drivers used their profits to participate in the expanding consumer culture noted above (see module 6), but they also used accumulated profits to purchase their own vehicles, establishing themselves as small-scale owner-operators. The most successful drivers owned multiple vehicles and employed a number of mates and drivers. When commodity prices declined in the late 1960s and 1970s, the motor transport industry was one of the few viable spaces of economic opportunity for young men in the city. As more men embraced the possibilities of driving work, increased competition made it more difficult for drivers to profit from their work or enforce standards in the profession.

New models, old business

The importation of wooden-sided vehicles was banned in 1966. While many of these vehicles remained on the road, government officials encouraged drivers to embrace new technologies. The wooden bodies were said to splinter in the case of crash, causing further injuries among passengers. Many drivers continued to operate mammy trucks as cargo transport, particularly in rural areas and small towns, and many children still rode mammy trucks to school through the 1980s. Increasingly, however, the wooden trucks found themselves in competition with new imported buses. Today one rarely sees the wooden-sided trucks – they have been replaced by imported, second-hand buses and vans – and the transport industry remains the subject of significant controversy in Accra and around the country. Drivers in the late twentieth century faced new challenges as the cost of vehicles increased and mechanics struggled to find spare parts to maintain the existing vehicle stock. Modern novelty quickly gave way to nostalgia for the old vehicles and the period of relative prosperity that they represented. Even in the midst of technological change, the labor practices of drivers, which privileged small-scale car ownership and the apprenticeship models of training persisted at the center of a transport industry that was dominated by the motor vehicle.

Economic crisis and creativity

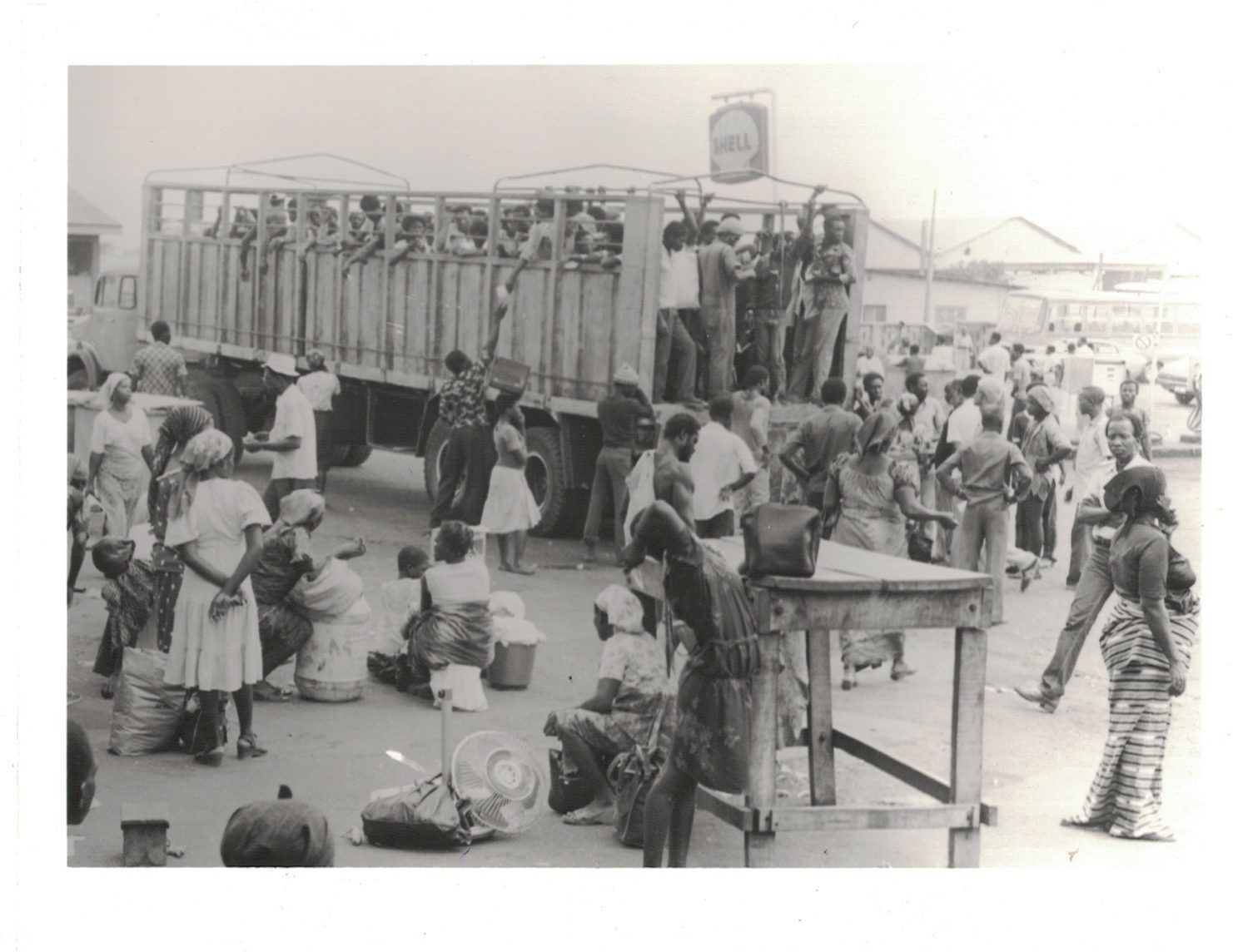

As the country’s economic conditions began to deteriorate in the late 1960s, drivers faced increasing questions about their economic practices. Like market women and other entrepreneurs, government officials and the general public frequently targeted drivers, who were seen to profit off of the suffering of others, providing an essential public service for personal gain. Newspapers are full of complaints about drivers who engaged in “profiteering” that was widely viewed as both immoral and criminal. While the industry’s reputation suffered within this broader context of social and economic decline, young men continued to flock to the industry, seeking low barriers of entry and the promise of a steady wage. In 1983, as the country grappled with the repatriation of thousands of Ghanaians who had been expelled from Nigeria and a persistent drought that crippled the country’s economy, a combination of foreign currency shortages and oil shocks meant that petrol, tires, and spare parts were also in short supply. Drivers continued working during this period, taking advantage of their strategic position within the broader economy to sustain their households and using their knowledge of the vehicle to invent creative ways to keep themselves and their passengers moving. Demand, however, remained high and many passengers, such as those seen below, resorted to more extreme measures in order to get around.

Conclusion

The history of motor transportation in Ghana is one of creativity, adaptation, and resistance. Over the course of the twentieth century, drivers and their passengers creatively adapted both the imported technology of motor transportation and indigenous practices of mobility, circulation, and exchange to forge a uniquely Ghanaian culture of automobility. The trotro can be seen as a local expression of global technological forms. But a close reading of the history of this technology through the lives of the drivers and passengers whose actions gave meaning to technological form suggests that it was much more than that. Mammy trucks and trotros connected Africans in twentieth-century Ghana to global networks and cultures, but they also challenged and often defied the imperialist impulses of technological and technocratic regimes of colonial and postcolonial governance. At the same time, however, we must be careful not to romanticize a system that presents profound challenges and insecurities for both drivers and passengers. This persistent defiance – a working outside of the system – often means that the motor transport industry in Ghana is labeled and dismissed as part of a demonized “informal economy.” But as these stories suggest, there may be much we can and should learn from the networks, cultures, and practices that develop alongside the grassroots infrastructures and public services that mammy trucks and trotros provide.

References

Jennifer Hart, Ghana on the Go: African Mobility in the Age of Motor Transportation (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press), 2016.

Jennifer Hart, “Motor Transportation, Trade Unionism, and the Culture of Work in Colonial Ghana” (Special Issue: “Labor in Transport: Histories from the Global South [Africa, Asia, and Latin America] 1700 to 2000”), International Review of Social History 59 (2014): 185-209. Reprinted in Labor in Transport: Histories from the Global South, c. 1750-1950, Stefano Bellucci, Larissa Rosa Correa, Jan-George Deutsch, and Chitra Joshi, eds (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 2014.

Jennifer Hart, “’One Man, No Chop’: Licit Wealth, Good Citizens, and the Criminalization of Drivers in Postcolonial Ghana,” International Journal of African Historical Studies 46:3 (December 2013): 373-96.

Jennifer Hart, “’Nifa Nifa’: Technopolitics, Mobile Workers, and the ambivalence of Decline in Acheampong’s Ghana,” African Economic History 44 (2016): 181-201.

Steven Feld, Jazz Cosmopolitanism in Accra: Five Musical Years in Ghana (Durham, NC: Duke University Press), 2012.

Ato Quayson, Oxford Street, Accra: City Life and the Itineraries of Transnationalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press), 2014.

Lindsey Green-Simms, Postcolonial Automobility: Car Culture in West Africa (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press), 2017.

Jennifer Hart is an Associate Professor of History at Wayne State University, where she teaches courses in African History, Digital History, History Communication, and World History. Her 2016 book, Ghana on the Go: African Mobility in the Age of Motor Transportation (Indiana University Press) was a finalist for the African Studies Association’s Herskovits Prize.