Restricted Cargo: Chinese Sailors, Shore Leave, And The Evolution Of U.S. Immigration Policies, 1882-1942

Andrew Urban, Rutgers University

Table of Contents

- Immigrant or Sailor? Assigning Legal Status in the Era of Exclusion

- Asian Labor and Global Shipping During the Long Nineteenth Century

- Wages, Nativism, and Chinese Seamen

- Regulating and Policing Sailors’ Shore Leave

- Intermediaries: Brokers, Bondsmen, and Other Service Providers

- Anti-Chinese Activism in San Francisco and Great Britain: Shared Agendas

- Refusing to Stay on Ship

- World War II and the Changing Politics of Chinese Restriction

- Conclusion

- Archives and Works Consulted

Immigrant or Sailor? Assigning Legal Status in the Era of Exclusion

When “Ah” Kee submitted a habeus petition to the federal Court for the Southern District of New York in November 1884, demanding his release from prison, legal precedents determining how government officials were to enforce the 1882 Chinese Restriction Act were scarce. Born in post-annexation Hong Kong as a British colonial subject, Kee had sailed from Kolkata (Calcutta) on the American bark, the Richard Parsons. How Kee had ended up in Kolkata went unreported, but court documents did note that he had been “following the high seas” for some time. Kee likely understood New York to be a global port that was “free” insofar as a seaman could come ashore and negotiate the terms of their next contract without government restrictions on their participation in the local labor market. Upon the Richard Parsons’ arrival in New York, however, the ship’s captain claimed that the new law prohibiting the immigration of Chinese laborers meant that Kee was forbidden from disembarking. When Kee snuck ashore, he was detained by a federal marshal monitoring the piers.

The court freed him. Justice Addison Brown wrote in his opinion that “The well-known use and meaning of… ‘Chinese laborers’ have no reference to seamen in the ordinary pursuit of their vocation on the high seas, who may touch upon our shores, and may land temporarily for the purpose only of obtaining a chance to ship for some other foreign voyage as soon as possible, and who do not intend to make any stay here, or enter upon any of the occupations on land within this country.”[1] Brown believed that the Chinese Restriction Act was not intended to hamper commerce in American ports by putting onerous regulations on how ships handled the hiring and discharge of seamen. It was in the United States’ interest, free trade advocates and backers of Brown’s line of thinking maintained, to accommodate vessels regardless of what country they were registered to or whom they hired as crew. With freight and passenger routes connecting New York to Europe, South and Central America, the Caribbean, and East and South Asia, by 1900 the city’s open-for-business attitude toward imports and exports had helped it surpass London as the world’s busiest port.

Despite Brown’s optimism that local labor markets favorable to the conduct of global maritime trade could coexist with restrictive immigration laws, to anti-Chinese exclusionists bent on closing legislative loopholes, Chinese sailors remained a dangerous source of potential unauthorized entries. As John Hager, Collector of Customs for the Port of San Francisco underlined, in an 1886 letter to the Secretary of the Treasury, Chinese “seamen individually are recruited from the very element which the law prohibits from entering the country. When ashore, they are soon lost sight of in the vast throng of their countrymen in this city.”[2] To Hager and other exclusionists, permitting Chinese sailors to come ashore was akin to inviting them to remain in the United States illegally.

* * *

Chinese sailors helped make late-nineteenth-century globalization possible by providing an experienced and geographically dispersed source of maritime labor that was available for hire for relatively low wages. Economists estimate that the tonnage moved in international shipping increased by four hundred percent between 1870 and 1913. Trade ballooned at the same time the world was becoming a more restrictive place to non-white migrant laborers. Globalization produced new inequalities, highlighted by the greater freedom of movement that goods enjoyed in comparison to human workers.

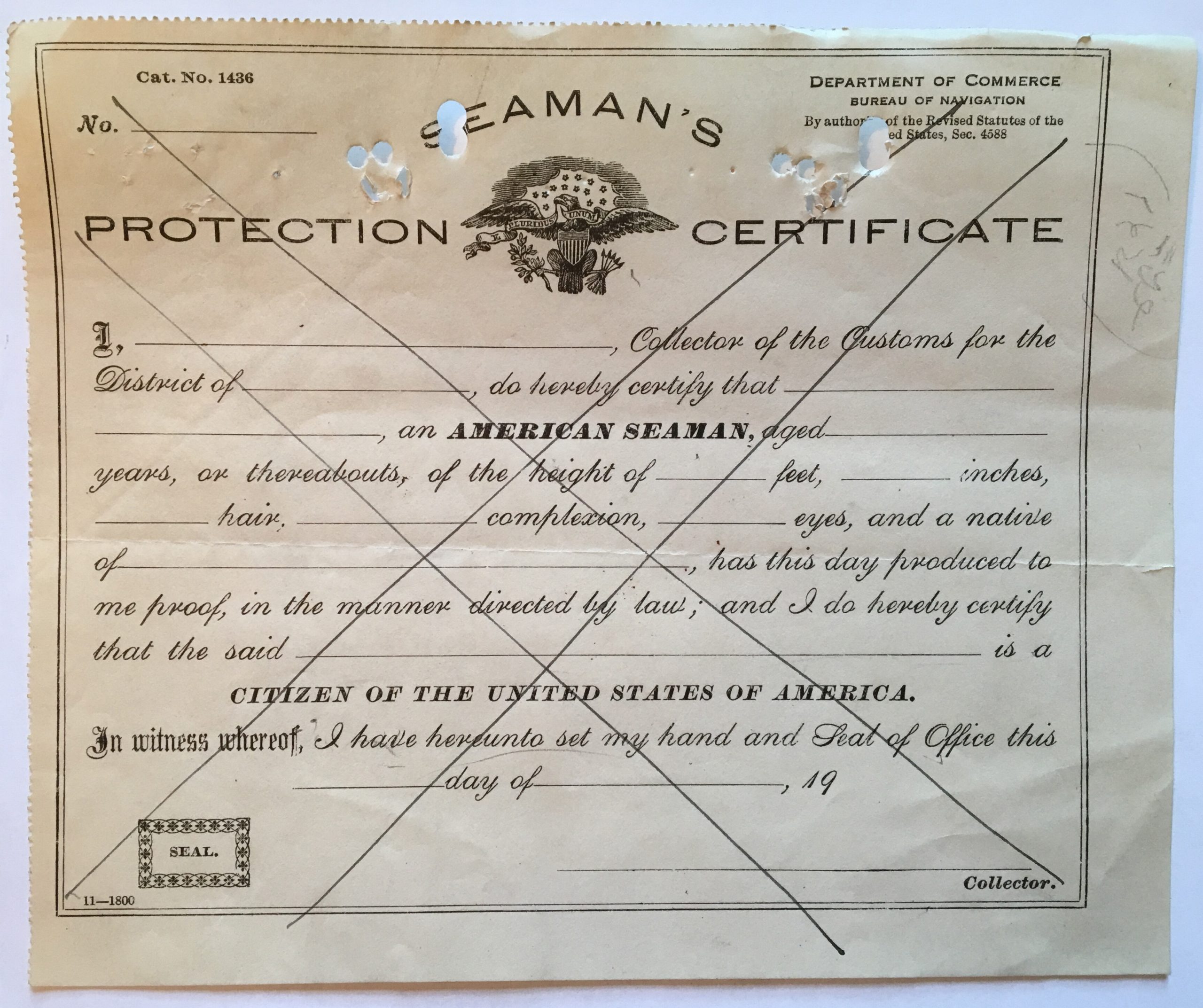

As this exhibit documents, rather than granting Chinese and Asian sailors the liberty to come ashore and “ship for some other foreign voyage as soon as possible,” as Brown put it, the United States instead introduced controls that limited seamen’s access to labor markets in American ports. Immigration policies placed Chinese seamen under the control of employers who, after 1902, were required to take out security bonds indemnifying them against unauthorized immigration. Alternatively, ship captains could deny Chinese sailors shore leave altogether. When Chinese seamen arrived in American ports on contracts that had ended, they were still not free to come ashore – unless they could finance their participation in the American labor markets by arranging for security bonds on their own accord.

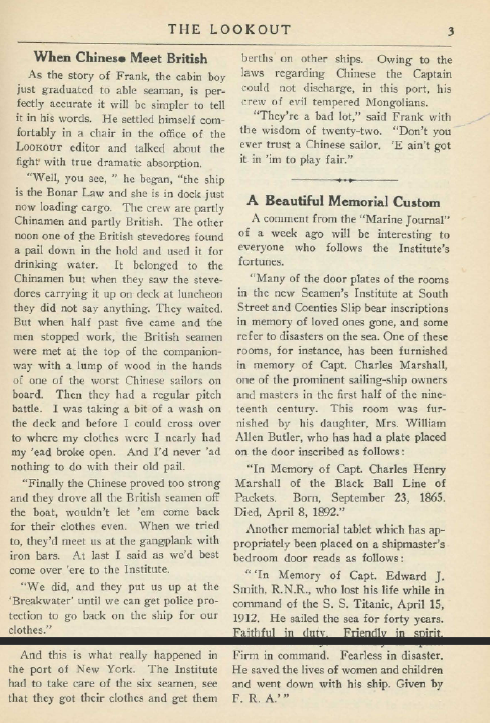

While historians have acknowledged that racism against Asian and other non-white sailors permeated the ideologies of unions representing seamen in the United States and Britain, the main thrust of these studies has been to weigh this racism against the progressive reforms that maritime workers simultaneously pursued. White sailors racialized Asian laborers as “coolies” who were immune to the appeal of better wages, working conditions, and rights that white seamen demanded. Yet it was immigration policies rather than any innate predisposition to exploitation that transformed Asian seamen into the very thing that white seamen feared: unfree labor.

Asian labor and global shipping during the long nineteenth century

From the 1870s until the Second World War, economic historians estimate that British-flagged vessels shipped more than half of all international cargo. Shipbuilders in Great Britain were quicker to shift production to the manufacture of screw propeller-powered steamships, and competitors who were latecomers to this transition struggled in the face of comparative advantages that British firms had gained. William Wallace Bates, a shipbuilder who served as United States Commissioner of Navigation from 1889 to 1892, lamented in an 1893 book on the “shipping question” that in his first year as commissioner, twenty-one of the thirty vessels exporting 37,974 tons of American flour to foreign markets were British-flagged, with American-flagged and -built boats accounting for only three of the shipments.

Even though American shipping companies involved in the transpacific passenger and freight trade had been reliant on Chinese sailors since the late 1860s, Bates blamed British companies for the spread of what he considered to be insidious employment practices. “Suppose we buy our ships in Liverpool,” Bates asked, “shall we get our sailors from Hong Kong?”[3] Critics claimed the disappearance of American sailors and boats was also a matter of naval capability in times of war, which made the United States’ reliance on foreign seamen and ships an issue of national security. Even though naval officers commended Chinese seamen for their combat roles on warships in the Philippines during the War of 1898, exclusionists continued to allege that Chinese seamen could not be trusted to be loyal during times of war.

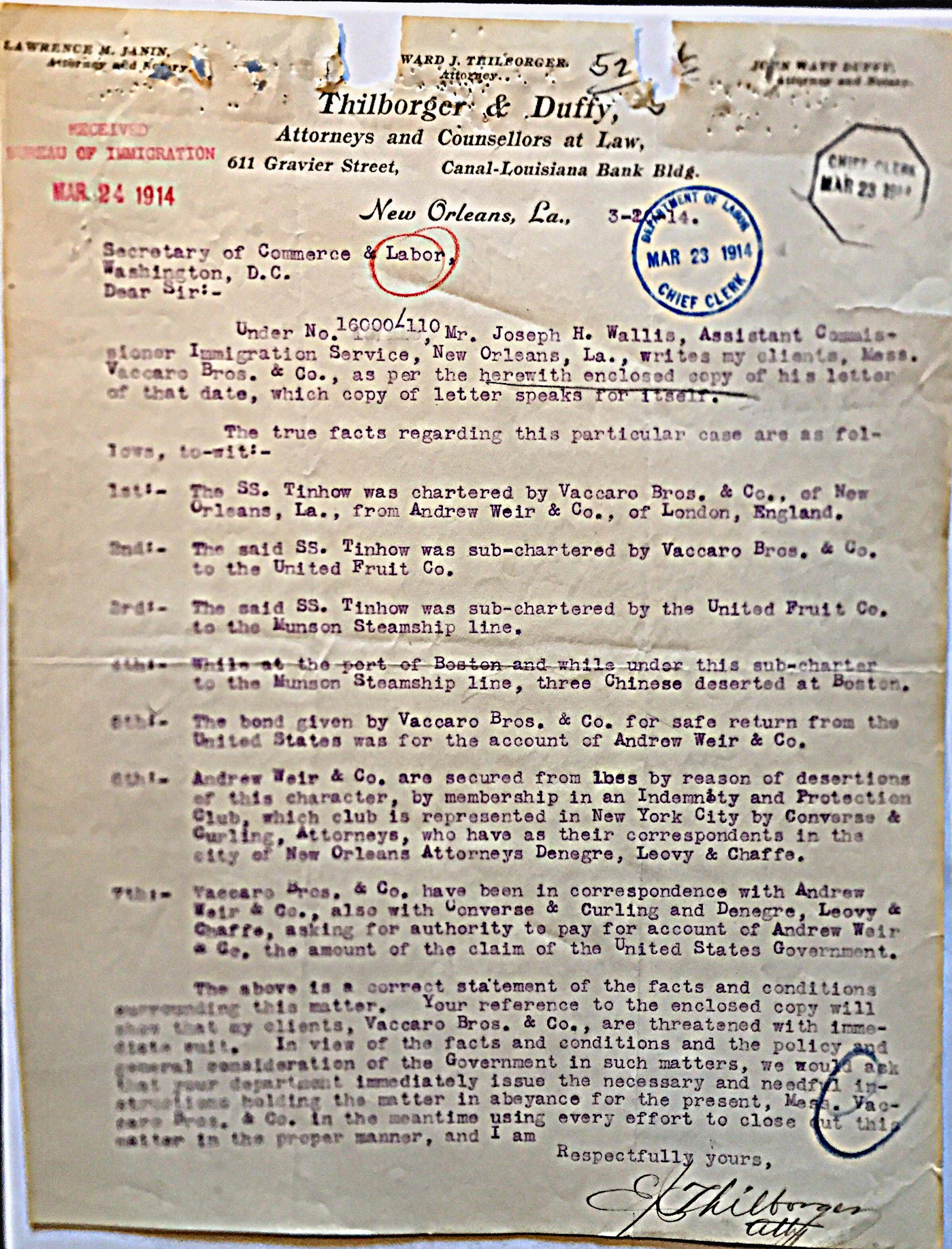

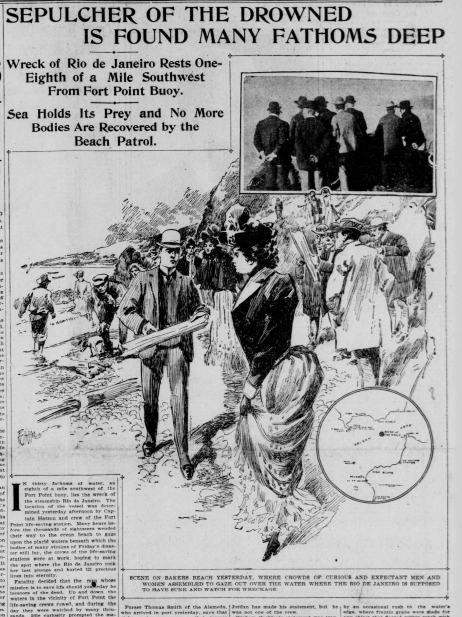

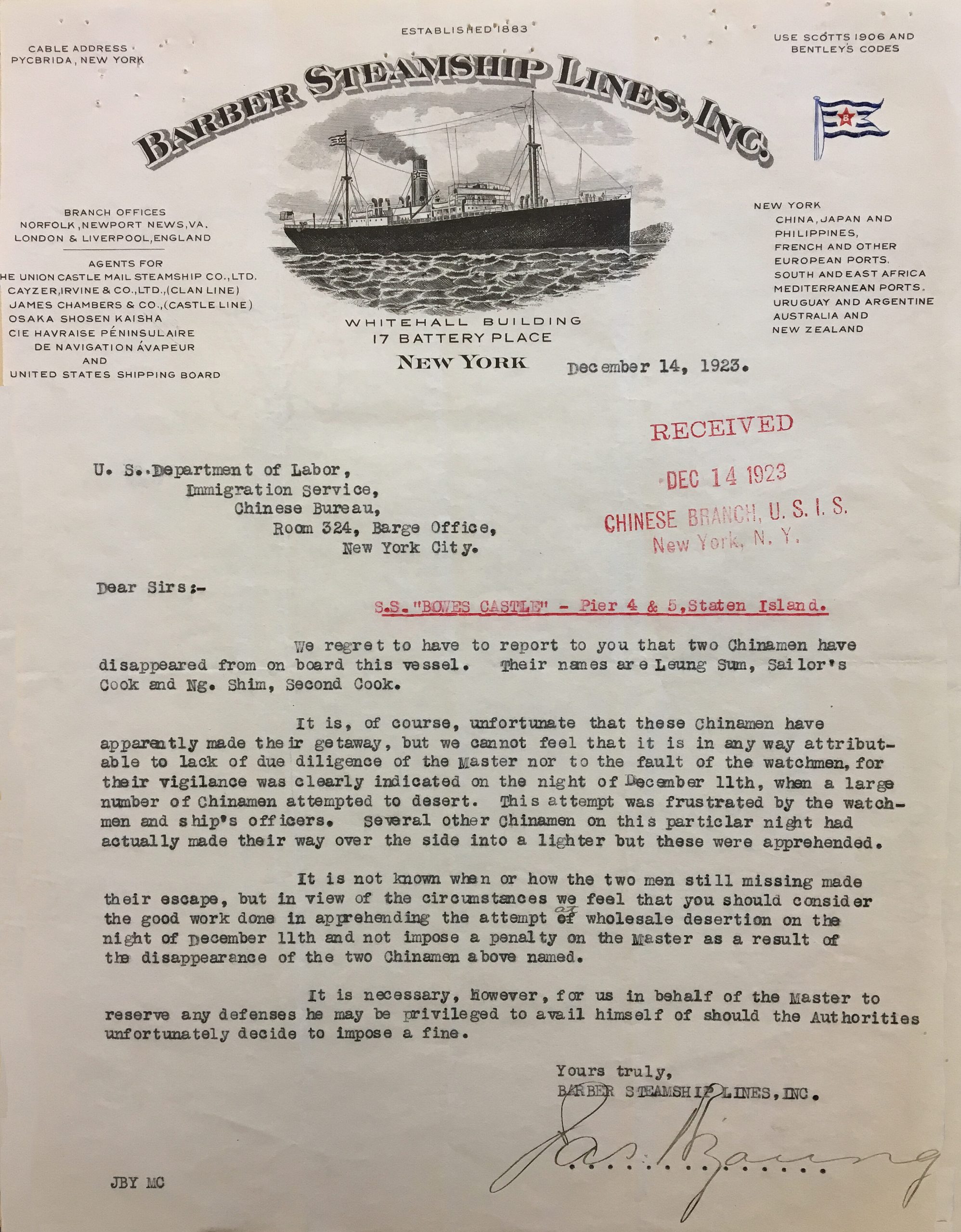

The vessels featured in this exhibit demonstrate the reach of British shipping. More importantly, they demonstrate how Chinese sailors had become a labor standard in all fleets, in all oceans. The S.S. Harfleur, whose Chinese crew clashed violently with immigration officials in Texas, was a British-flagged vessel in the Louisiana-based Union Sulphur Company’s fleet, shipping sulfur to sales offices and distribution centers that the company maintained in Rotterdam, Marburg, Cette, and Marseilles. The S.S. Bones Castle, an American-flagged vessel from which a group of Chinese sailors deserted in New York harbor in 1923, shipped cotton from the Atlantic Coast to Shanghai on the Barber Steamship lines regular freight route to the “Far East.” Chinese sailors were also employed on “tramp” steamers, which made on-demand deliveries of freight. The S.S. Tinhow, for instance, was a British-flagged steamer owned by Andrew Weir and Company based out of London. Between 1912 and 1914, however, the steamer was subcontracted to at least three different shipping companies and moved lumber from Mobile, Alabama, to Havana, Cuba, and fruit from Central America to New Orleans and Boston. Even though the jobs and routes changed, the use of crews that included Chinese sailors remained consistent.

After three Chinese seamen deserted the Tinhow in Boston, immigration officials sought payment on bonds that had indemnified the United States against the sailors’ unauthorized entry. A letter from the New Orleans-based attorney to the Vaccaro Brothers Company requests additional time to sort the matter out, stating that the London owners of the vessel had an insurance policy that would cover penalties associated with desertion.

Wages, nativism, and Chinese seamen

The transition from sail to steam, which occurred gradually over the course of the second half of the nineteenth century, helped to devalue the labor of all seamen. Steamships deskilled maritime labor, especially when it came to the creation of new positions such as firemen, where the primary element of the job was to ceaselessly shovel coal into a furnace. Changes in maritime technologies and labor needs were not the fault of Asian sailors, who had worked on American and British sail ships as well. But to white seamen their increased employment became a visual symbol of how white mariners had lost control over the means of production.

White seamen directed animosity and mistrust at Chinese sailors who, regardless of how much time they had spent in American and British ports, were depicted as foreign competition. These representations ignored the real factors that determined maritime labor costs. The most significant factor determining labor costs was where a boat hired crews and what the prevailing wage in those ports was. Wages in Asian ports were less than wages in American ports, but so were wages paid to seamen – regardless of their race – shipping from British and European ports as well.

Foreign ships that called on American ports contended with higher prevailing wage rates that might lure crews away. To prevent this, shipping companies withheld wages until the roundtrip voyage was completed. Desertion still occurred in considerable numbers, even if it meant losing promised pay. Andrew Furuseth, a Norwegian immigrant to the United States and the influential president of the International Seamen Union (ISU), wrote in a 1915 editorial calling on Congress to regulate (white) foreign sailors’ right to shore leave that when the crew of a boat receiving twelve to sixteen dollars in monthly wages docked next to a vessel where sailors received thirty to forty dollars a month, “The men receiving the lesser wage, if they be free to do so, will leave the vessel paying the lesser wage and obtain the higher wage in that port.”[4]In Furuseth’s vision, if foreign shipping companies faced widespread desertions, they would have no choice but to increase wages across the globe as a preventative measure. Furuseth’s calls for desertion coexisted with his simultaneous commitment to the complete exclusion of Chinese seamen from American job markets, whether they demanded higher “American” wages or not.

While Chinese seamen could be found working in any number of jobs on vessels, they were disproportionately employed as stewards, cooks, and firemen – positions that white sailors shunned for more skilled positions that earned higher pay. Freight and passenger lines prized Chinese sailors as workers who could be enlisted to do grunt work for low wages, a willingness that they attributed to race rather than to economic need and discrimination. Anti-Chinese activists invoked the familiar stereotype that Chinese seamen, like their counterparts who worked in land-based occupations, were “coolies.” As scholars of Chinese migration have highlighted, white commentators’ use of the term “coolie” only rarely referred to workers held in actual states of indenture or bondage. The prevalent use of the word calls attention to whites’ belief that Chinese laborers were racially incapable of resisting oppression and exploitation, and uninterested in being free. Chinese sailors’ willingness to live unfree and in degraded conditions, the white seamen’s unions claimed, meant that they would tolerate brutal working conditions and accept wages and victuals that white sailors could not survive on.

|

|

|

|

|

|

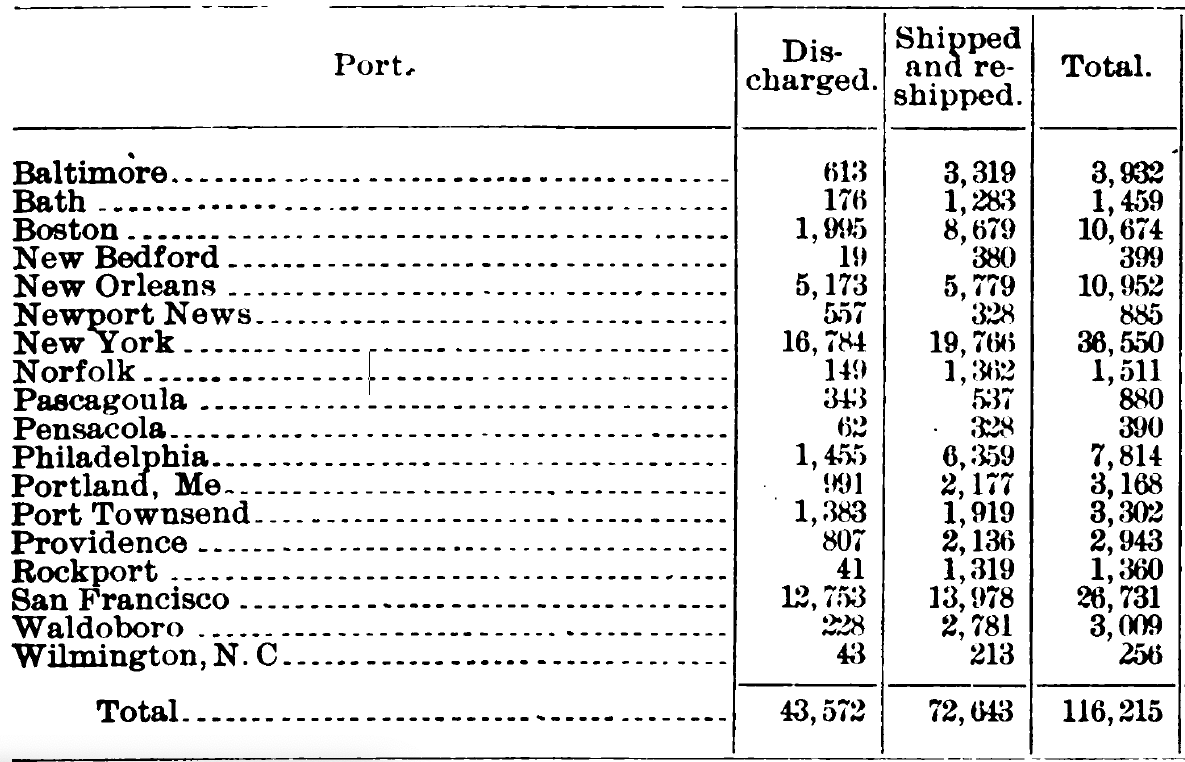

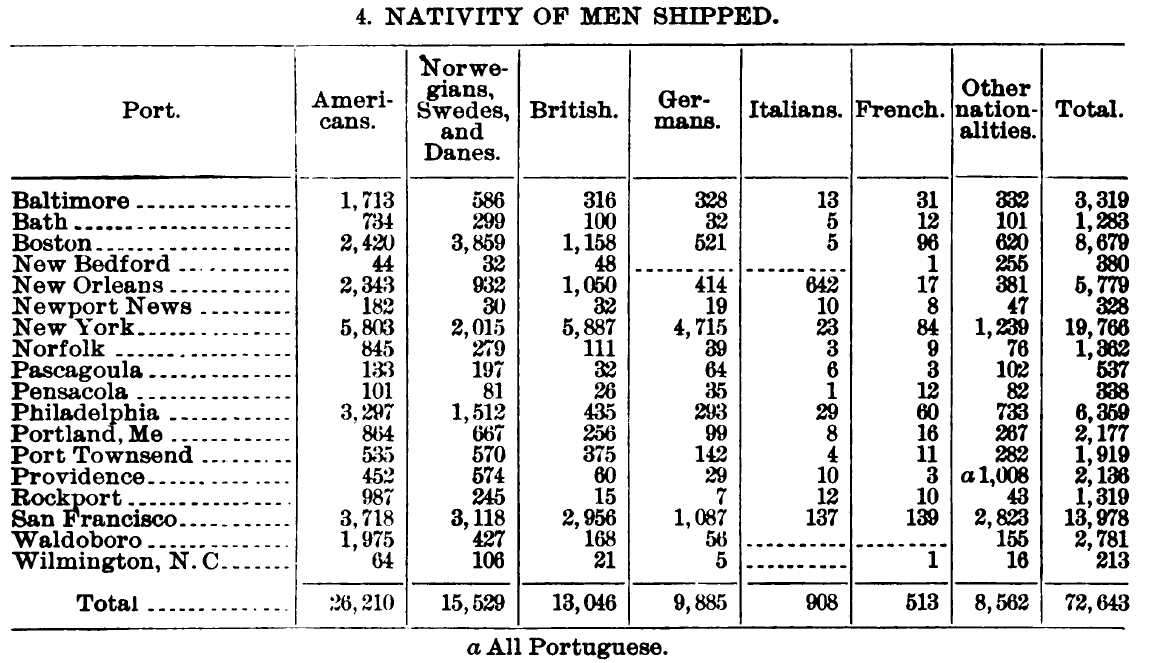

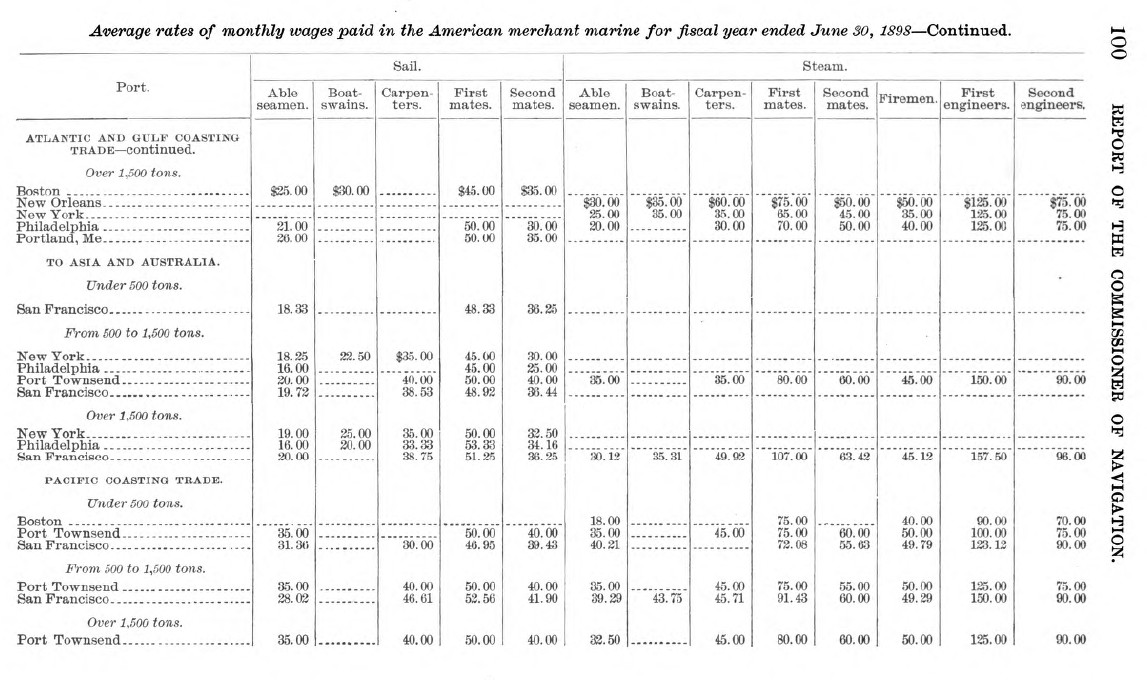

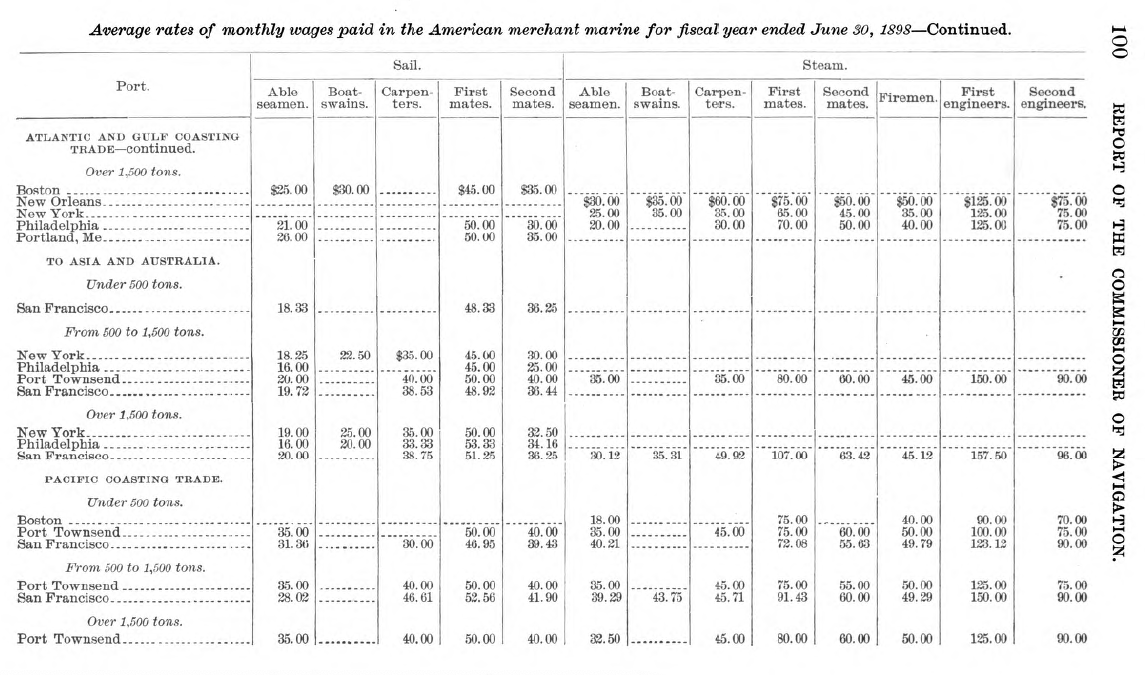

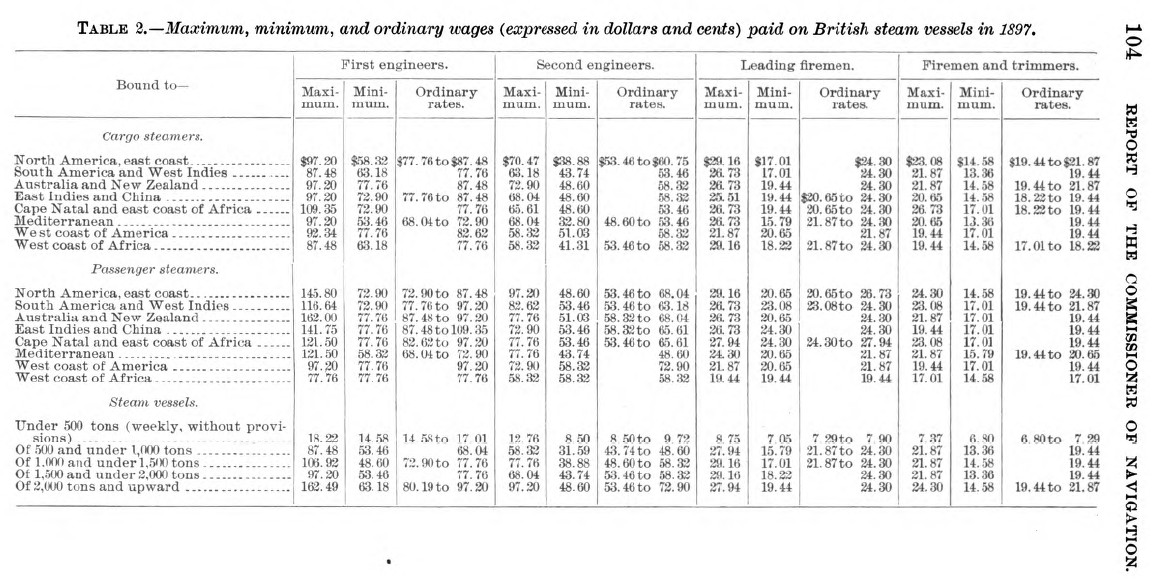

Figures 2-a through 2-f. Tables on discharges, nationality, and wages for seamen shipping in and out of U.S. ports. Source: U.S. Commissioner of Navigation, Report of the Commissioner of Navigation to Secretary of Treasury. 1898 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1899), 90, 91, 97, 100, 103, 104. Rights status: Image, courtesy of Hathi Trust Digital Library.

According to figures from the 1898 Report of the Commissioner of Navigation, which covered international trade for the fiscal year ending on June 30, 1898, American vessels moved approximately 11 million tons of goods into and out of American ports, with foreign vessels accounting for 36 million tons. Because most of the shipping to and from the United States was conducted on foreign-flagged vessels based outside the country, it followed that foreigners of all nationalities constituted the bulk of seamen employed in maritime labor. European immigrants rather than Asian immigrants represented most of the foreigners working American ports. Immigrant seamen based in the United States were also counted as foreign workers, even when they shipped from American ports.

The Commissioner of Navigation also tabulated comparative wage rates for seamen working American and British vessels making the same routes. The statistics were not broken down further by nationality or race. While Chinese sailors shipping from San Francisco to Hong Kong might be hired for Hong Kong wages, as was the case with crews on the Pacific Mail steamships, a Chinese sailor shipping between Cardiff and New York was likely to demand close to what a white sailor working the same route and position would demand.

Regulating and policing sailors’ shore leave

Even though the question of whether Chinese sailors might be considered immigrant laborers upon taking shore leave was raised almost immediately after the passage of the 1882 Chinese Restriction Act, Congress did nothing to further address the issue until 1902, when a draft version of what would become that year’s Exclusion Act required that each Chinese seaman taking shore leave be indemnified by a two-thousand-dollar surety bond. Republicans in Senate ultimately had the clause removed from the bill, out of concern that it would undermine the party’s commitment to pro-business policies supporting free trade. Republicans favored instead giving Treasury officials the case-by-case discretion to determine when a Chinese sailor needed to be bonded.

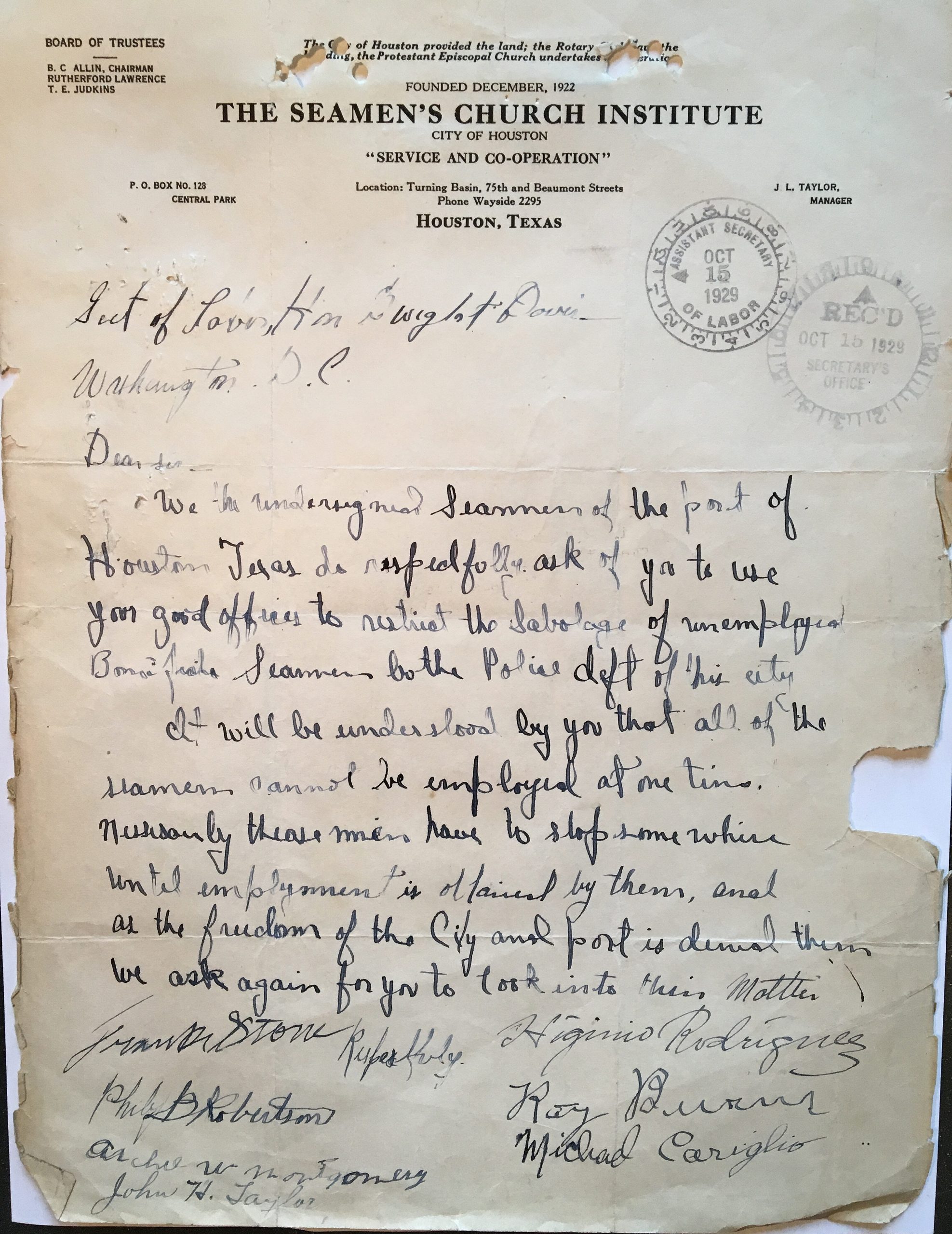

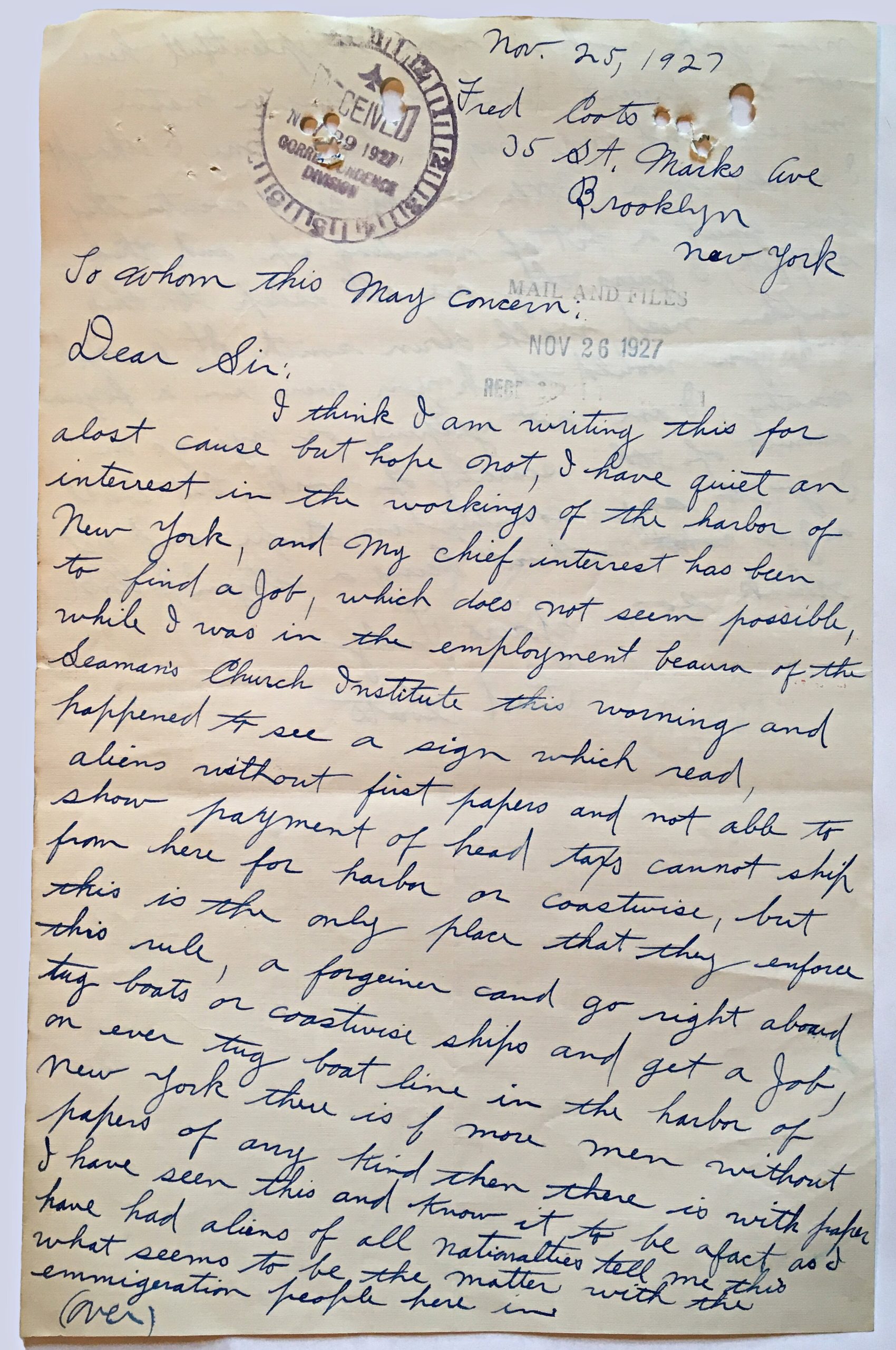

In practice, immigration officials used their discretionary powers to harass Chinese seamen while tacitly permitting foreign sailors who were white to desert and become immigrants. Beginning in 1903, under the leadership of Frank Sargent, a Roosevelt appointee who hailed from the ranks of organized labor, the Bureau adopted internal rules to regulate foreign sailors’ shore leave and to determine when bonds were to be issued. The Bureau emphasized distinguishing between “bona fide alien seamen” taking shore leave before reshipping, and sailors using this as cover to immigrate.[5] That this distinction could even be made was an oversimplification of how shore leave, labor markets, and migration worked. Foreign sailors might go ashore with plans to reship and end up remaining in the United States for any number of reasons, even though this had not been their intent.

From 1903 to 1917 only Chinese sailors were scrutinized by inspectors when seeking to go ashore, and only Chinese sailors were required to be indemnified, typically with five-hundred-dollar bonds, before landing. The money was forfeited if they failed to reship within thirty days. Foreign sailors from other nationalities were exempted from the bonding requirement. Moreover, immigration inspectors were ordered to instruct white sailors on how to seek admission as immigrants if they chose this course of action, so long as they were not ineligible to enter for the medical, political, or moral reasons that existed in the statutes as reasons for possible debarment.

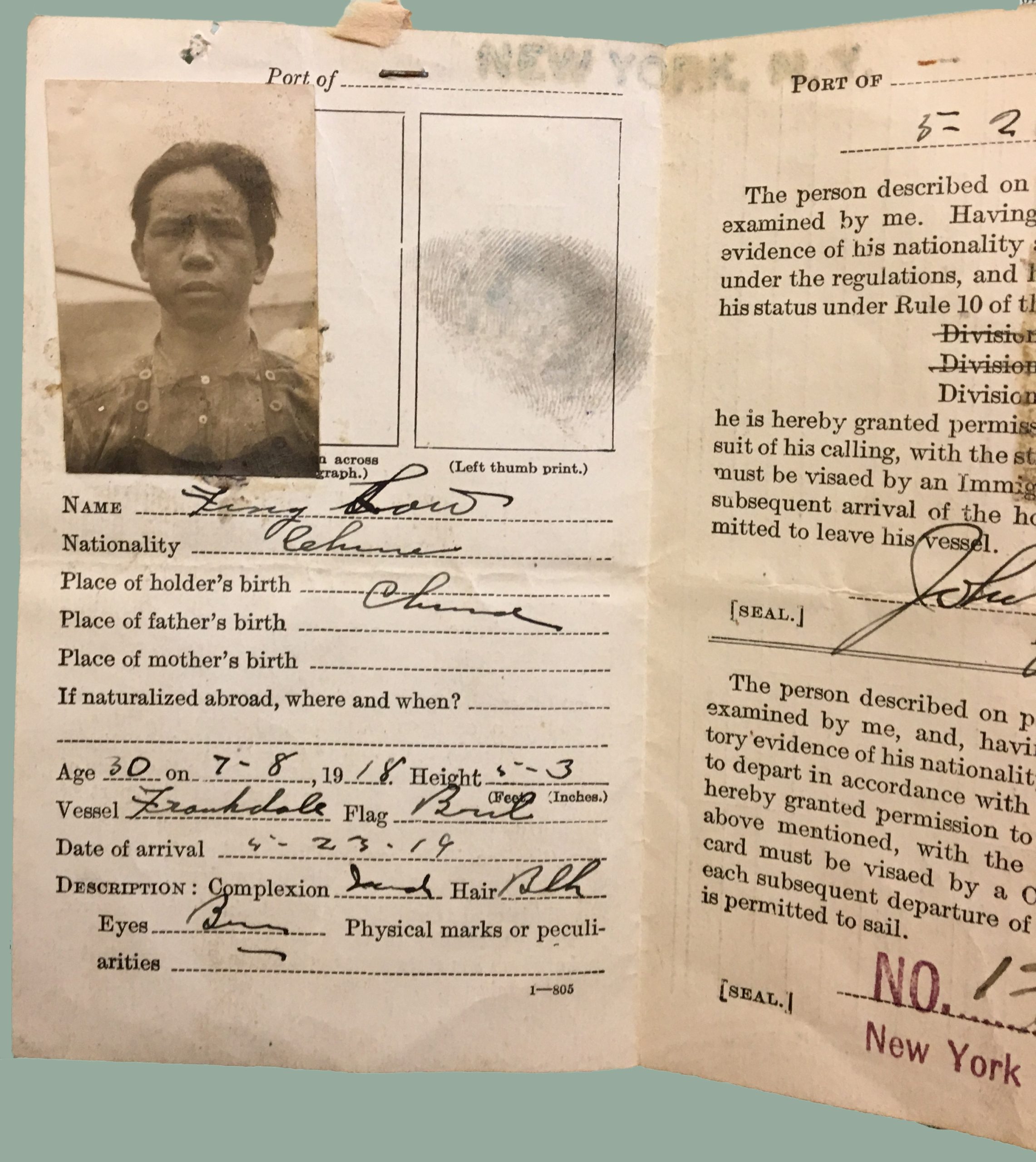

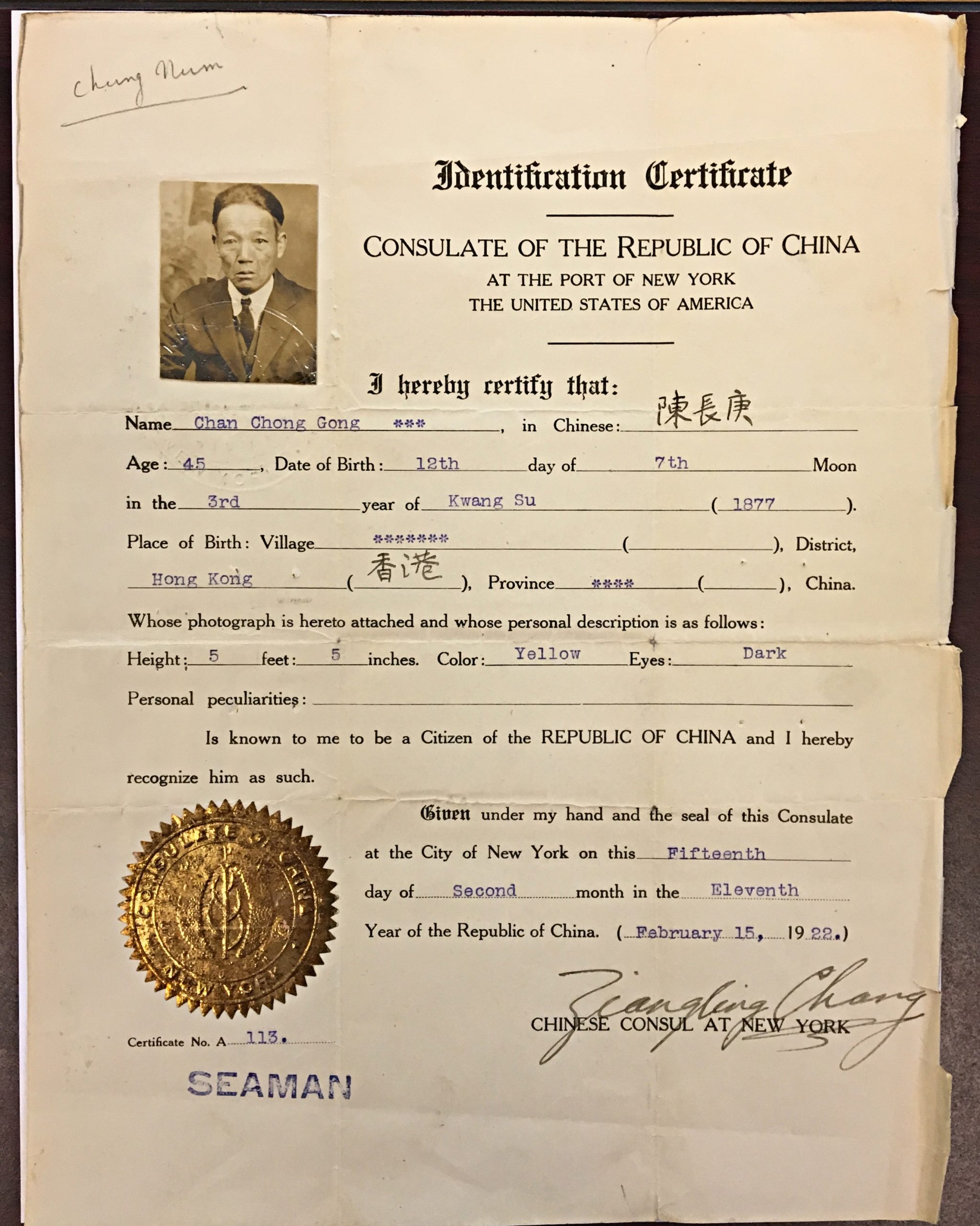

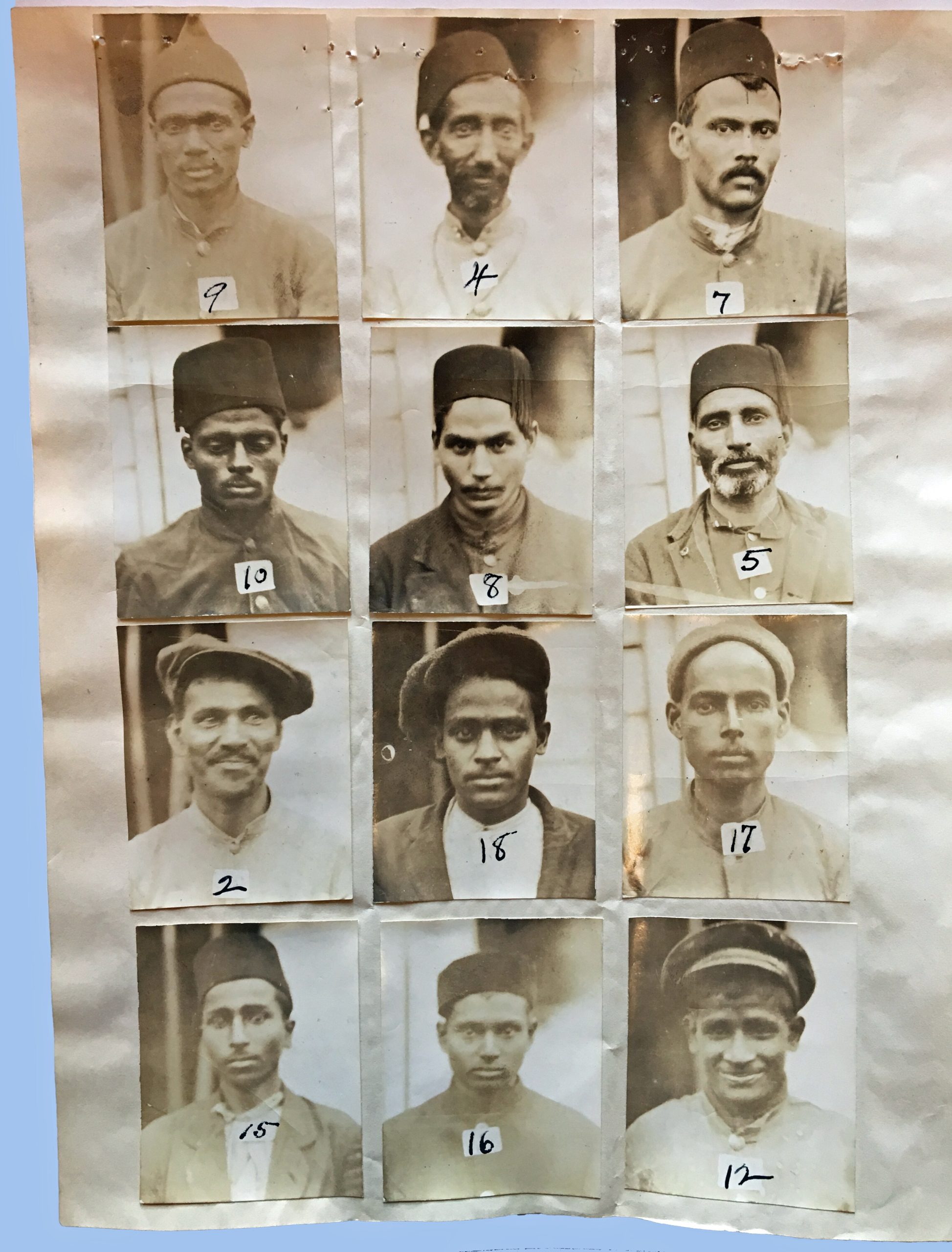

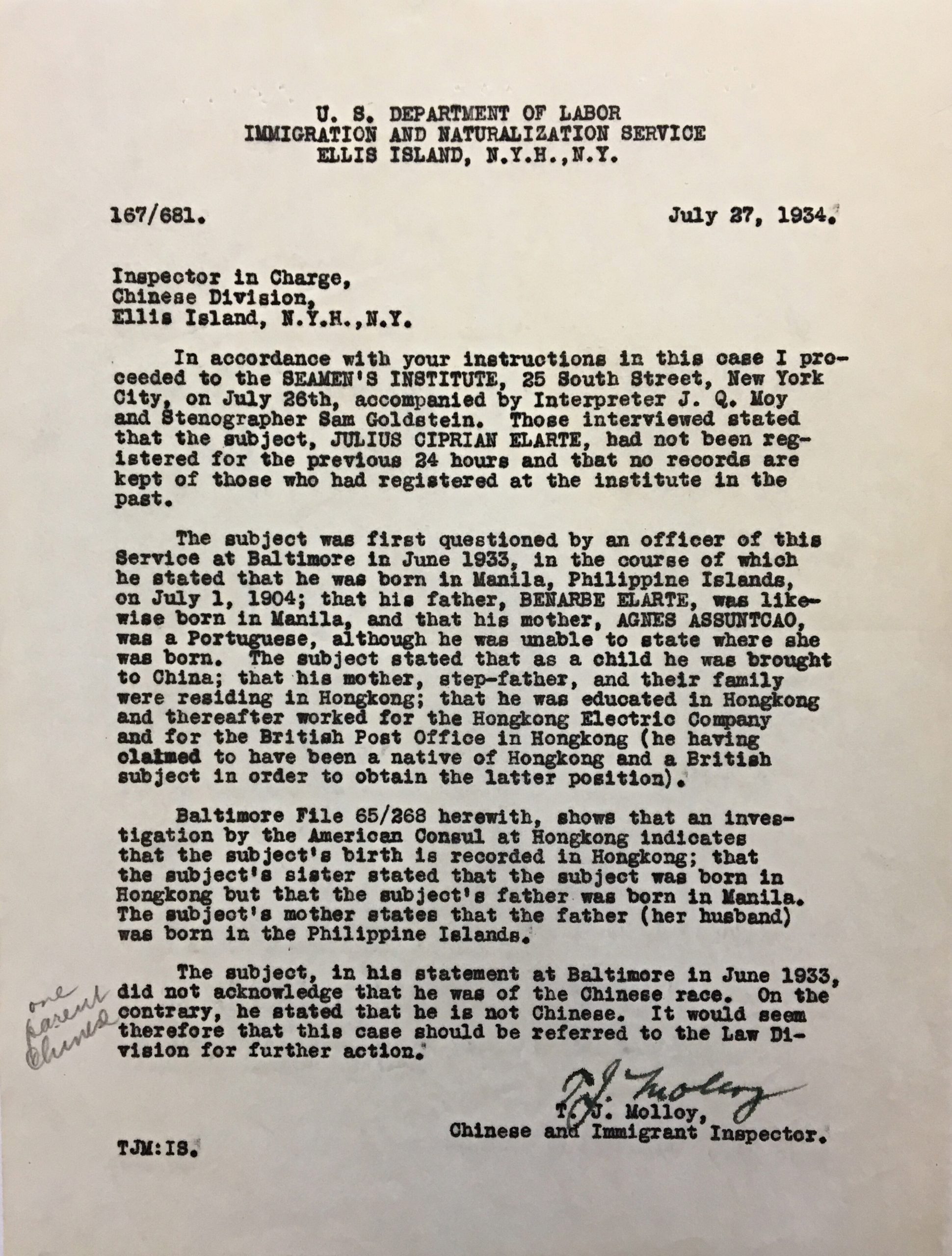

In response to lingering legal challenges as to whether the Bureau of Immigration had the authority to regulate shore leave, the 1917 Immigration Act stipulated that immigration officials were to inspect all foreign seamen being discharged from vessels and to require bonds or other security measures in cases where they had reasonable suspicion to believe a sailor intended to desert. Shipmasters were liable for a one thousand-dollar fine if they failed to “detain on board any such alien” that an immigration officer had declared inadmissible.[6] The 1917 Act also created an “Asiatic Barred Zone” from which immigration was prohibited, meaning that immigration officials would subsequently require all sailors classified as Asian to be bonded before landing – even though the legal question of whether immigration officials had the power to require “bona fide” seamen to take out bonds before coming ashore remained unresolved into the 1920s. To go ashore, Asian seamen were required to submit photographs, fingerprints, and biographical information to officials so that they could be monitored while in port and their departure compelled. It was only with the 1924 Johnson-Reed Immigration Act, which first introduced quotas on European immigration, that the pathway from sailor to immigrant was blocked for European seamen as well.

Intermediaries: Brokers, bondsmen, and other service providers

Emigrants from China to North America hailed from the same areas that Chinese seamen working on British, American, and European ships did: the Guangdong province and the Pearl River Delta region. Along with the nearby city of Hong Kong, these were the areas most transformed by European imperialism and the international export of local commodities and labor migrants in the mid-nineteenth century. Ethnic civil war in Taishan and the Siyi region of Guangdong, between Hakka migrants and the established Cantonese-speaking population, lead to over a million deaths and massive displacement that further drove migration. Proximity to British-run Hong Kong and the treaty port of Guangzhou meant that migrants from Guangdong and the Pearl River Delta region had access to shipping companies, labor recruiters, and creditors who brokered both emigration and maritime employment. Migrants from the area also went to Singapore in considerable numbers, where maritime jobs abounded.

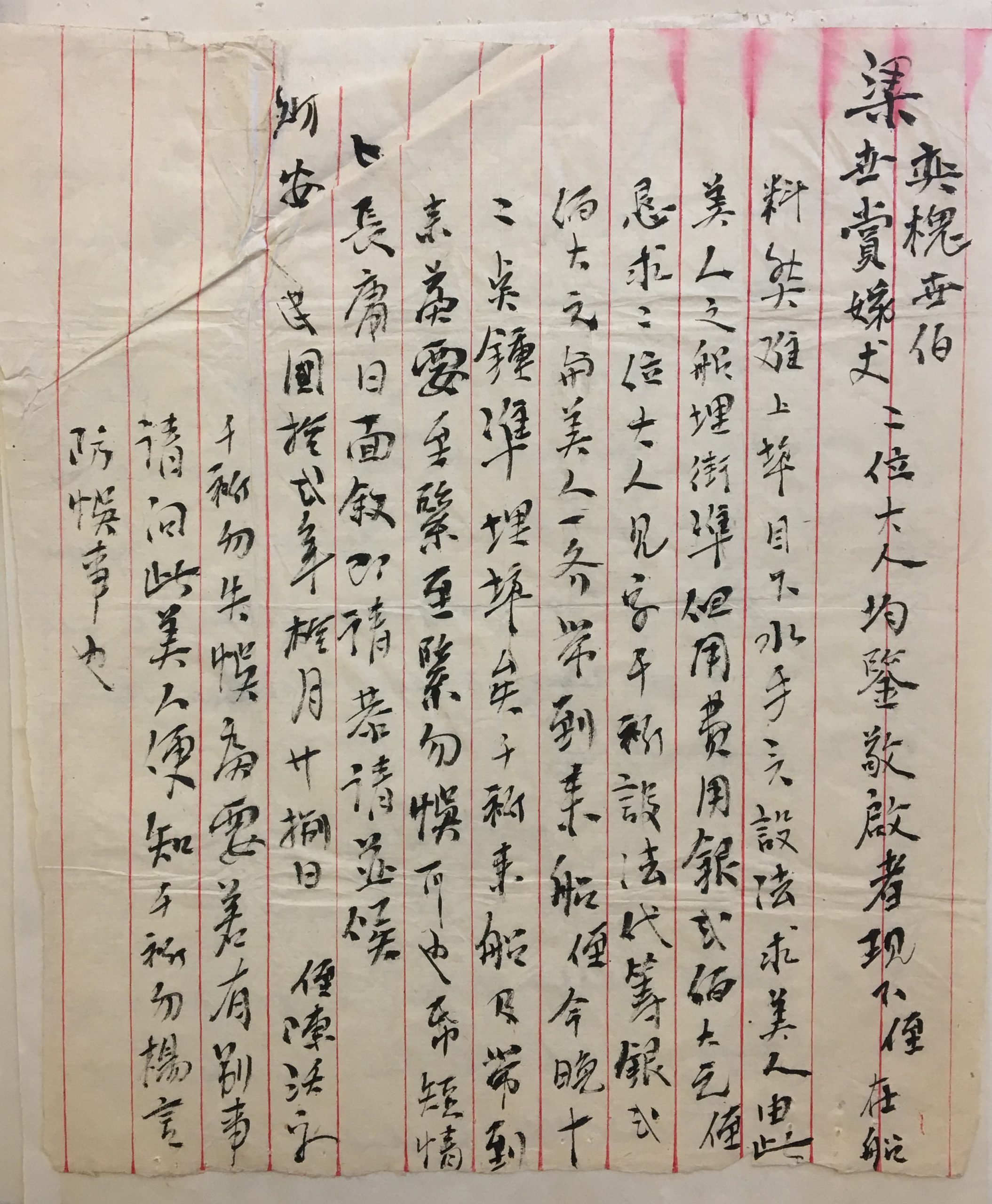

Mutual-aid associations in the United States and other places where the Chinese migrated were based in family, clan, and village connections, and coordinated the hiring of laborers locally. Bondsmen affiliated with mutual aid associations also brokered the temporary entry of Chinese seamen, as well as other classes of in-transit Chinese laborers – workers in Mexico and Cuba, for instance – who sought passage through the United States. Chinese intermediaries also brokered illegal entries. They sold false certificates of legal residency, organized illicit land and sea border crossings, and fabricated “paper” families that migrants used to deceive officials. Middle men conducted these businesses with the understanding that smuggling and the production of forged papers were accepted by Chinese communities as justified responses to unfair and explicitly discriminatory immigration policies.

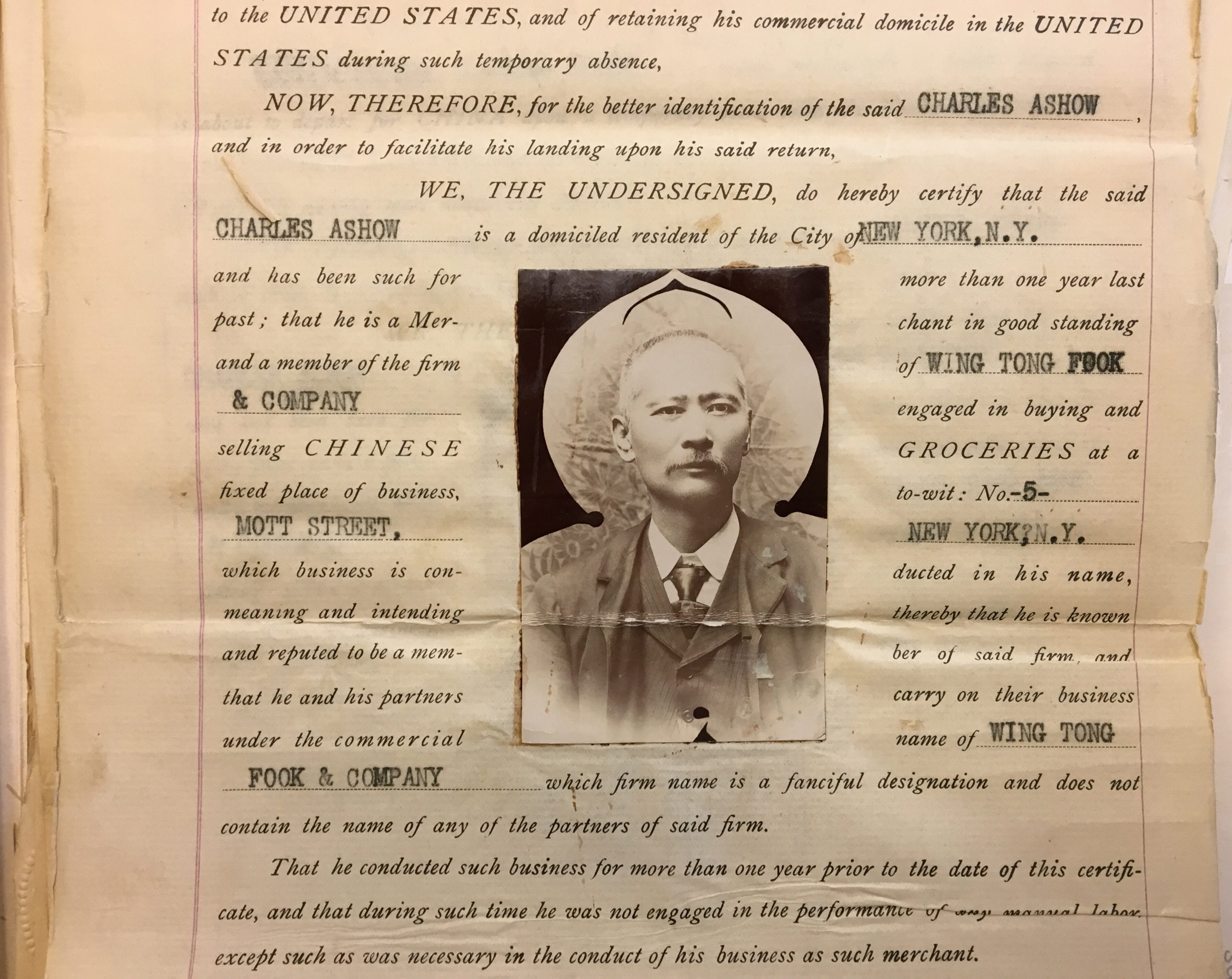

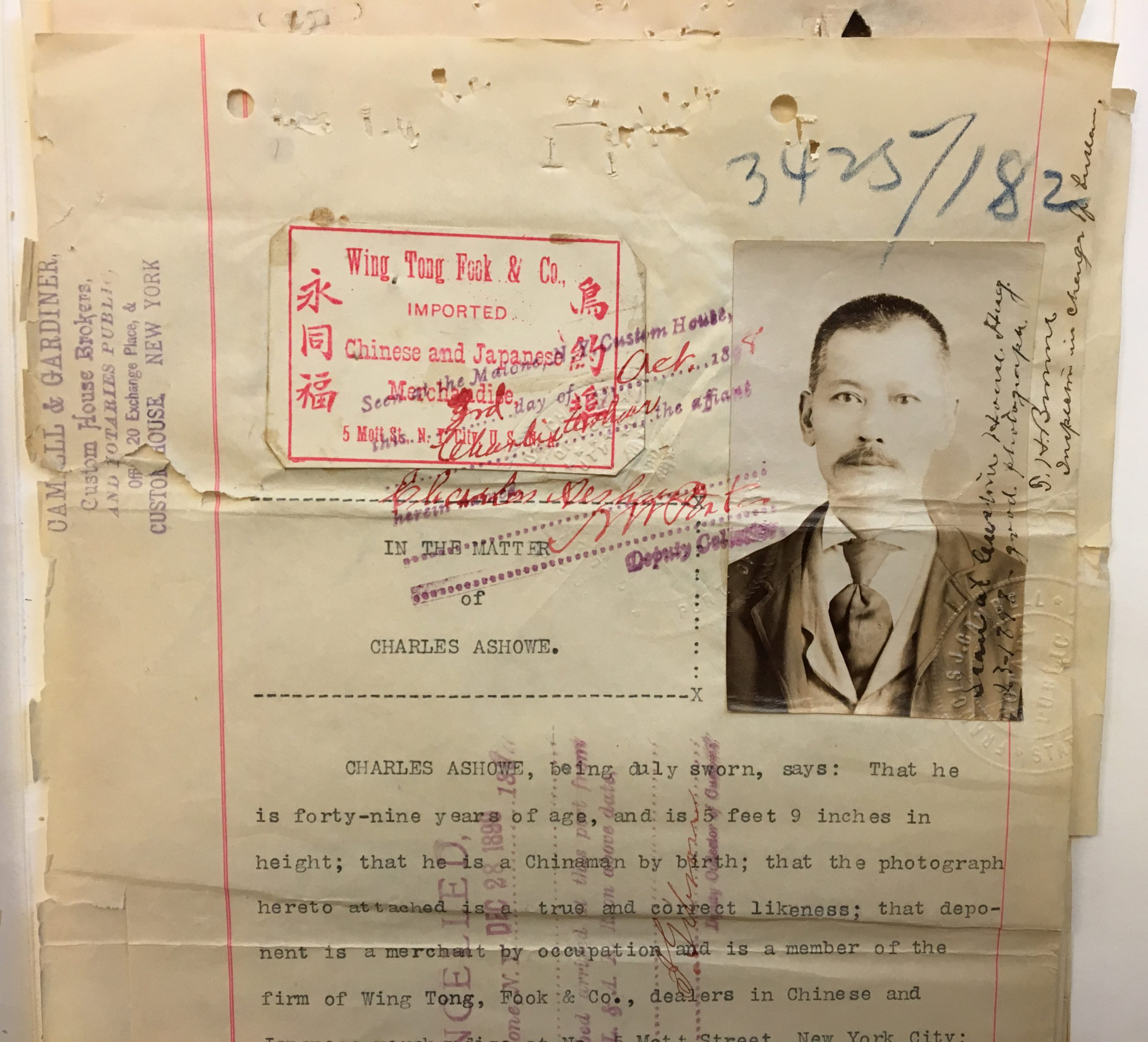

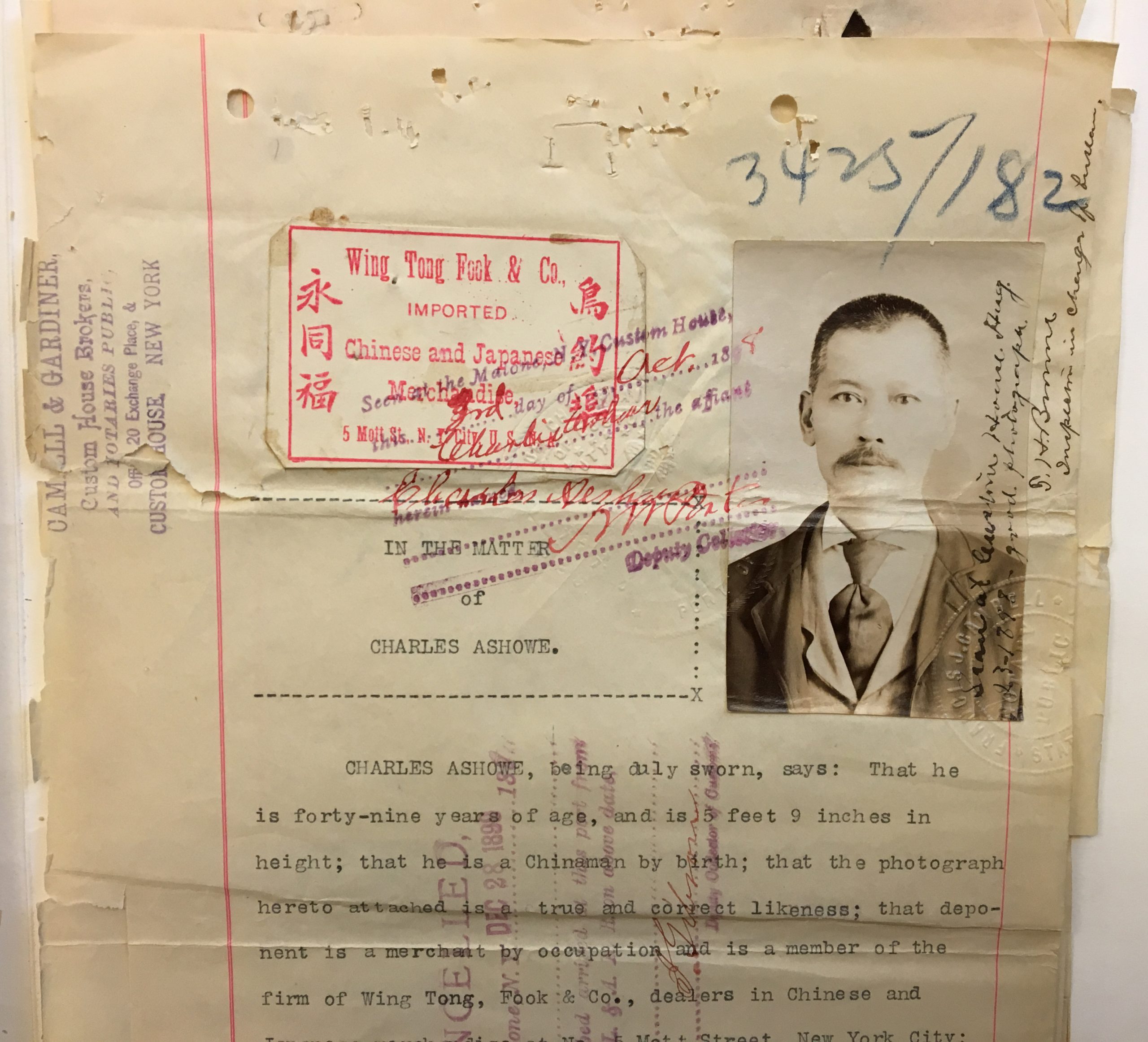

White officials and journalists claimed that Chinese bondsmen were sinister “crimps” who undermined white sailors by making low-wage Chinese seamen available for hire on the cheap. This is what officials alleged was the case with Charles Ashow (also spelled Ashowe and Arshowe), the Chinese-born proprietor of a boarding house at 67 Cherry Street in Lower Manhattan, which he ran with his wife Mary, the American-born daughter of Irish immigrants. Ashow’s “Chinese hotel” – as inspectors called it – catered to Chinese stewards, cooks, and firemen temporarily in port. Frank Sargent, the Commissioner General of Immigration, accused Ashow in 1904 of possessing the “full authority and control of Chinese of the nautical class in New York City.”[7] The reality was more ambiguous. Ashow may have profited from his role as a housing provider, bondsman, and labor broker, but officials provided no specific evidence indicating that he held Chinese sailors in a state of indenture. Still, in 1907, when Ashow prepared to depart for China and filed for the paperwork that would allow him to reenter the United States as a merchant upon his return, immigration officials rejected his application.

The Institute’s main building, which loomed over the East River, is featured on the cover. |

|

Anti-Chinese activism in San Francisco and Great Britain: Shared agendas

San Francisco was the epicenter of anti-Chinese activism in the late-nineteenth century United States, and exclusionists railed against the fleets of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, Dollar Steamship Company, and Occidental and Oriental Steamship Company, which employed Chinese crews almost exclusively. It is estimated that between 1879 and 1906, the Pacific Mail and Occidental and Oriental Steamship companies employed at least eighty thousand Chinese seamen on their transpacific routes. Chinese sailors who signed articles of employment in Asian ports were paid fifteen dollars a month, which was half of what white seamen shipping from San Francisco would earn on a transpacific voyage.

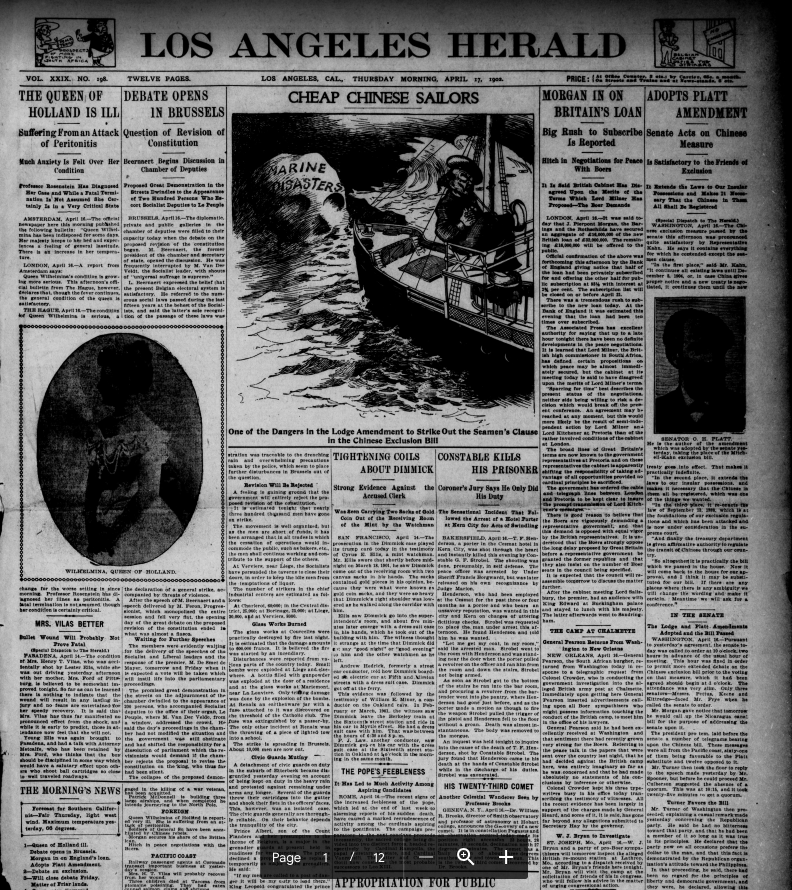

To prevent shipping companies from hiring their crews on the Asian legs of journeys, white sailors lobbied Congress to regulate in racial terms who could work on American-flagged ships. As early as 1904, the ISU submitted a memorial to President Roosevelt asking him to issue an executive order classifying Chinese sailors as among the classes of laborers designated for exclusion.[8] The 1915 Seamen’s Act, which outlawed criminal punishments for deserters and guaranteed seamen’s right to shore leave, included measures designed to prevent Chinese sailors from being the beneficiaries of the reforms. The Act mandated that seventy-five per cent of crew members on a ship had to be able to communicate in the language of a vessel’s officers. Robert La Follette, the Progressive Republican Senator from Wisconsin who sponsored the bill that would become the 1915 Seamen’s Act, claimed during a Congressional debate that the language provision would mean that passengers on a vessel in distress would not have to rely on “Chinese stupefied by opium” for their rescue.[9] Enforcement of this measure was lax, however, and the Act only applied to vessels that sailed under the American flag.

In Britain, white seamen organized in the National Sailors’ and Firemen’s Union (NSFU) sought to prohibit Chinese, Malay, and “Lascar” sailors – the general and at times indiscriminate term applied to South Asian seamen – from hiring onto ships in British ports. Although white sailors working on British ships had little ability to control how labor was employed in Asian ports, they were adamant that they had the right to bar the importation of colonial labor practices into job markets they defined and defended as domestic. As historian Sascha Auerbach documents, the three-year period of 1905 to 1908 saw a sharp rise in the number of Chinese seamen signing articles of employment in British ports. In London, 448 Chinese seamen shipped in 1905, but by 1908 that number had risen to 1,700. Whereas in 1905, 1,424 Chinese sailors departed from Liverpool, Glasgow, Cardiff, Barry, and Newport combined, by 1908 the numbers for those ports had increased to 5,600. Chinese sailors represented only a small percentage of the total number of foreign seamen shipping from British ports. Still, this did not stop the NSFU and allies from ramping up efforts to exclude Chinese sailors from employment. Like American trades unionists, British seamen argued that Chinese seamen, lacking sufficient English language skills, endangered passengers on steamships. The 1906 Merchant Shipping Act that Parliament passed required that sailors take a language test, but Chinese sailors from Hong Kong and Singapore were able to claim exemption as British subjects – a loophole that the NFSU vehemently protested. In 1908, when the Huddersfield sank off the Cornish coast, the NSFU blamed a Chinese sailor whose lack of English and mutinous attitude for the botched rescue that ensued – even though the seaman in question was Brazilian.

White British seamen also used violence to drive Chinese sailors from jobs. In May 1908, a series of riots broke out in London in which mobs prevented Chinese seamen from boarding the vessels that had hired them. The 1911 Seamen’s Strike in Cardiff resulted in attacks on Chinese sailors and on Chinese laundries and boarding houses in the city. In 1919, white mobs rioted in sea ports across Great Britain. Vigilantes targeted non-white seamen from Asia, Africa, and the West Indies whom they accused of having stolen jobs from white mariners conscripted into the navy during the First World War. In 1925, Parliament passed the Special Restriction (Coloured Alien Seamen) Order, which required seamen of color to register as aliens while in British ports, unless they could prove they were British subjects. This proved challenging for sailors who were not regularly issued passports when shipping from colonial ports.

The exclusion of Chinese and other Asian sailors from labor markets was a political cause that white sailors across the world embraced in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Antipathy toward Asian seamen provided a source of solidarity for white sailors who, in other contexts, might see themselves in nationalistic terms as economic antagonists. As historian Lauren Tabili argues, when seamen of color from Asia, Africa, or the West Indies sought employment in British ports, their goal was to “obtain employment under European contractual conditions, with vastly improved wages and rations, shipboard living conditions, and chances of surviving the voyage.”[10] This was the same motivation that drove white British and European sailors, as well as Asian sailors, to desert in American ports, where higher wages could be found. In Asian ports, the interwar period saw Asian sailors engage in strikes and work actions aimed at shipping companies and local subcontractors, and against British colonial authorities who governed trade. In 1922, for instance, an estimated 30,000 Chinese seamen went on strike in Hong Kong. Indian sailors formed unions in Mumbai and Kolkota in the 1920s and 1930s, which in addition to advocating for better working conditions and pay, also tried to eliminate the pernicious influence of serangs who acted as labor brokers.

|

Refusing to stay on ship

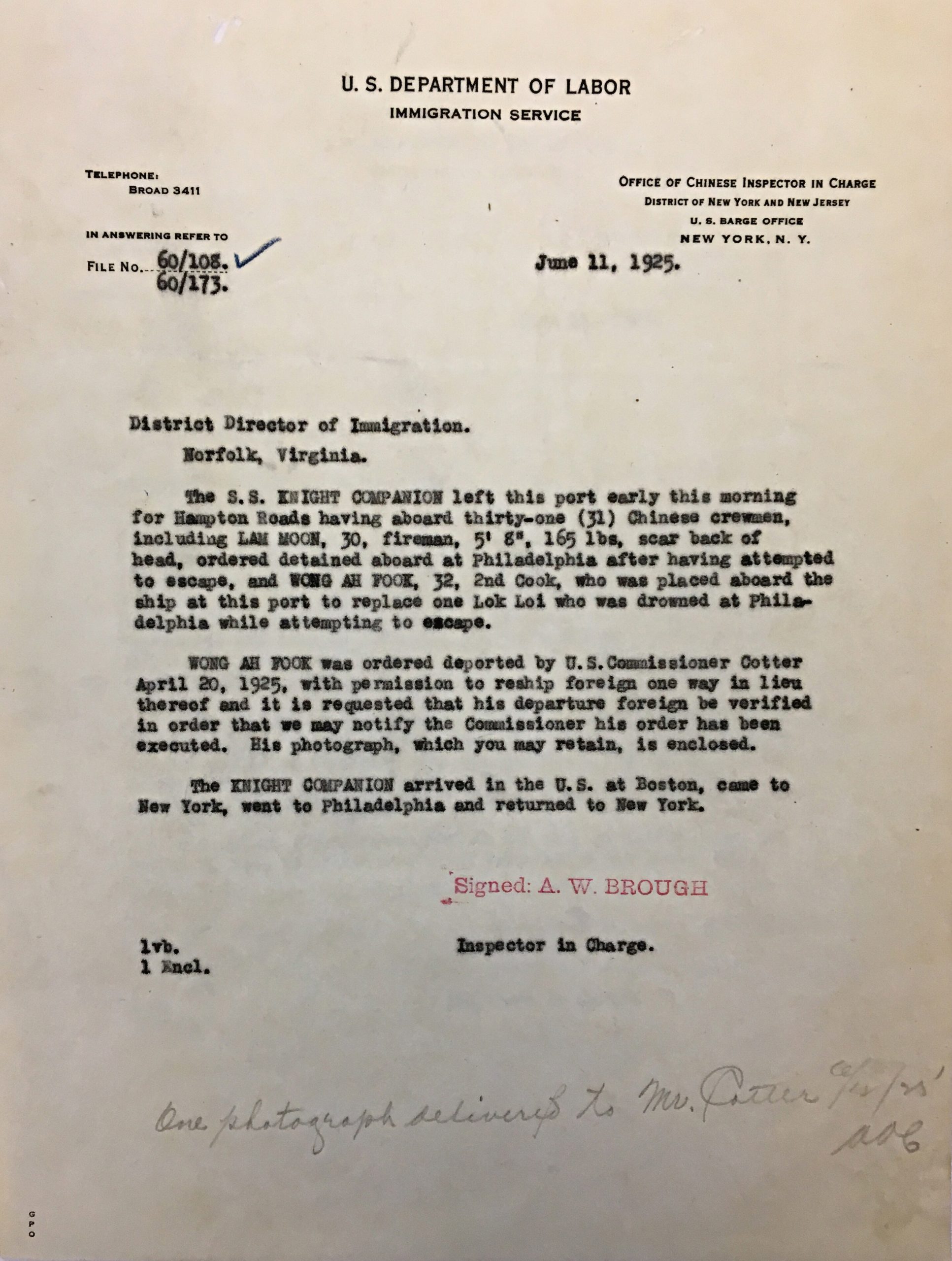

Despite being racialized as servile and exploitable, Chinese sailors were forceful in asserting their rights. When immigration officials tried to deny shore leave to Chinese sailors who had been confined to cramped quarters for weeks and months, the result was often mutiny. An inspector from the Galveston station, for instance, reported in August 1913 that when the British-flagged Harfleur arrived in Sabine, Texas, he had been unable to stop the vessel’s Chinese crew from going ashore without inspection or bonds. When the inspector conducted a headcount of the Chinese sailors upon their return to the Harfleur, he reported that “one of them kicked me in the stomach and one assaulted me from behind.” Although the ship’s captain temporarily restored order, after the muster was completed the Chinese crew began throwing “large chunks of sulphur” at the inspector and a watchman assisting him, which the ship’s officers only halfheartedly attempted to stop. As the Harfleur’s white British captain explained, he was indemnified against any legal costs associated with crew members’ desertions by insurers in London and he had no interest incurring the wrath of his crew by denying them the liberty to go ashore.

Tracking the number of sailors entering and exiting ports was difficult to do with accuracy. Immigration officials lobbying for more stringent restrictions seem to have exaggerated the number of Chinese sailors shipping from American ports, as was the case in 1913, when the Bureau’s annual report listed 40,000 active Chinese seamen. During the 1920s, as figures compiled by historian Anna Pegler-Gordon show, immigration inspectors administered between four and eight thousand examinations of Chinese seamen seeking to land – numbers that would include repeat entries by the same individual sailors. In 1920, 1,637 Chinese sailors were recorded as having deserted in New York, with an additional 135 deserting in San Francisco. That year, the two ports processed a total of 361,066 and 31,687 foreign seamen respectively. In comparison, in 1925, after quotas on European immigration were in place, 23,194 non-Chinese foreign seamen deserted in all U.S. ports out of a total number of 1,004,226.[12]

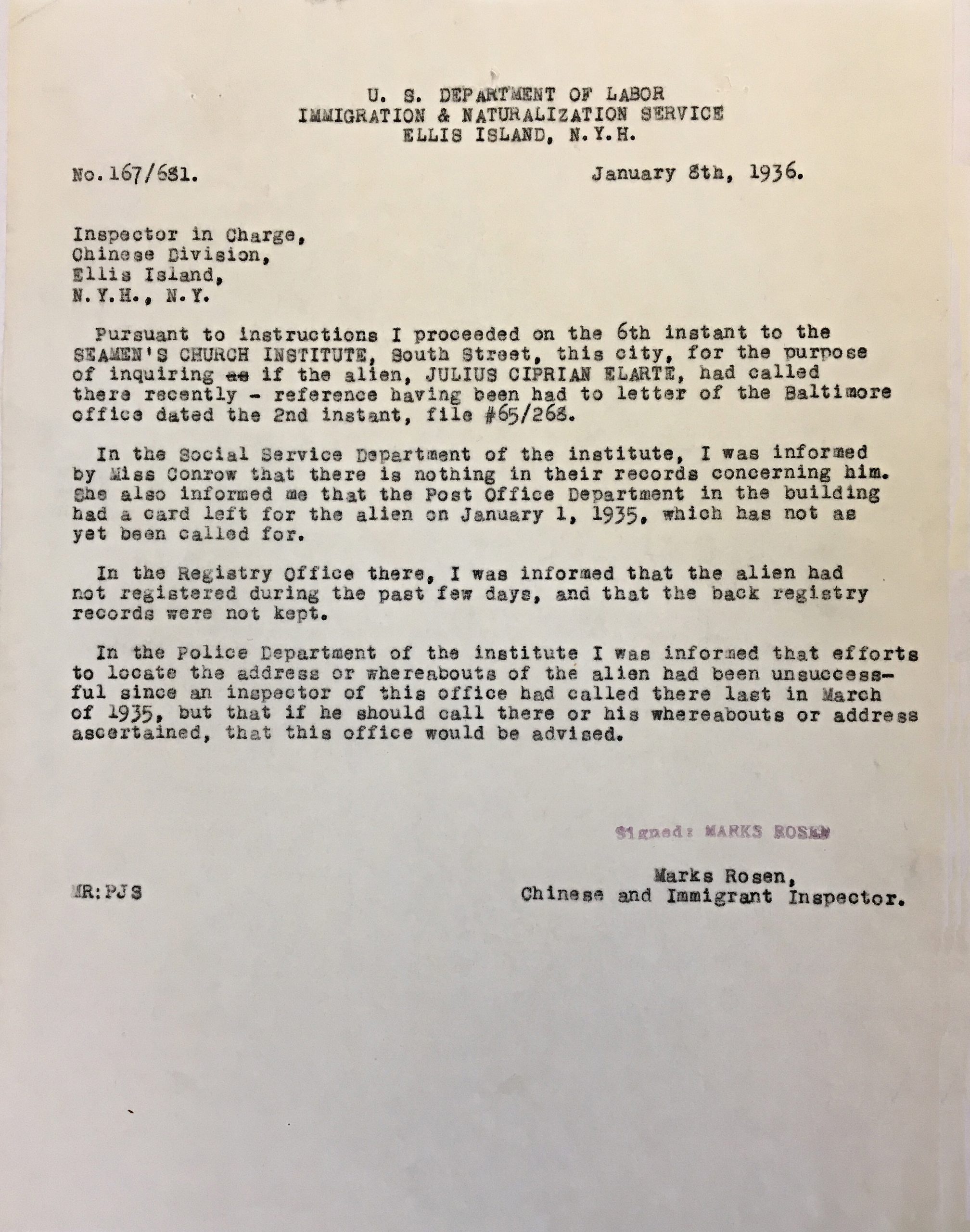

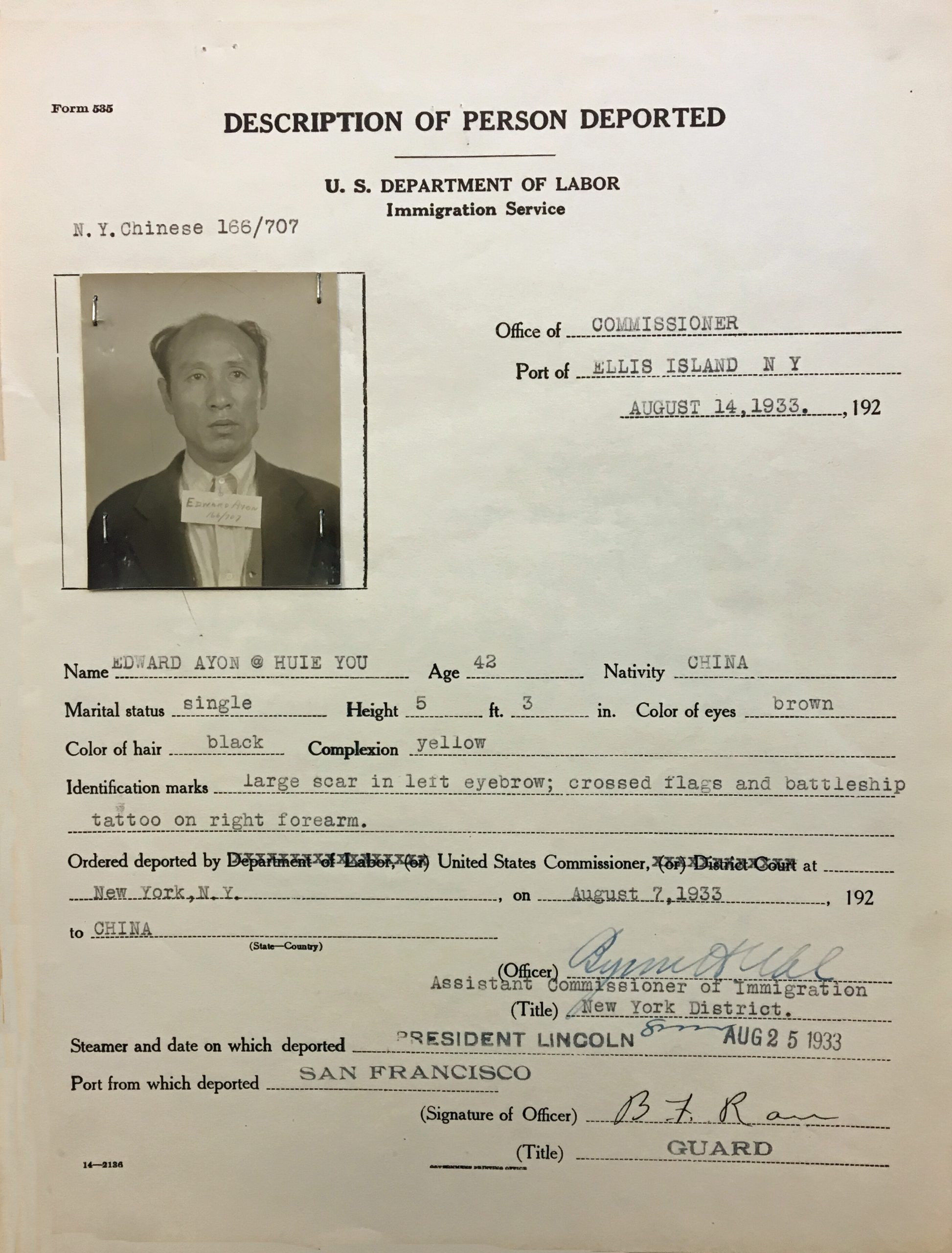

When Chinese sailors were granted shore leave and remained in the United States past the allotted time they were allowed – which by 1924 had increased to sixty days – they became subject to deportation. Deportation could occur years later after an arrest for opium possession – a common vice among sailors of all nationalities – or during an immigration raid on a laundry or restaurant business.

Immigration officials may have been limited in their power to stop bona fide foreign seamen from taking shore leave when ship captains took out bonds, but in cases where shipping companies enlisted immigration officials to assist in acts of detention – the gloves came off. On June 29, 1927, “armed with razors, wrenches, capstan bars and belaying pins,” the Chinese crew of the Rotterdam engaged in a mutiny and rushed the piers in Hoboken, New Jersey, where, after a battle with police, 54 were placed in the local prison. As the New York Chinese Seamen’s Institute would subsequently protest, the 84 sailors who had tried to come ashore wanted to leave their contracts after discovering that they had been duped into employment as strikebreakers. Transferred from the Hoboken jail to holding cells on Ellis Island, under the cover of secrecy the Chinese sailors were sent back to the Netherlands. When asked to explain the decision to hold the men, The Nation reported that the Commissioner of Ellis Island, Byron Uhl, had admitted that the act had not been done in accordance with any formal law or policy, but as a “friendly” gesture to the Holland American company.[13]

World War II and the Changing Politics of Chinese Restriction

During the Second World War, British merchant ships, their ranks depleted by naval conscription, hired more than 10,000 Chinese sailors to transport supplies back-and-forth across the Atlantic. Until September 1942, captains uniformly denied Chinese sailors shore leave upon arriving in New York, even though this violated both American and British maritime law. A series of violent mutinies and a rash of bad publicity put pressure on the British government to change its merchant navy’s policy. Anxious about Chinese deserters, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (the title the organization had assumed in 1933) joined with the U.S. War Shipping Administration to create the Alien Seaman Program. As historian Heather Lee has shown, the establishment of this new program meant that Chinese inspectors now served both the British and American governments when tracking down seamen who failed to return to their vessels. On January 9, 1943, inspectors interrogated over 1,500 Chinese residents of New York in a series of raids that disrupted restaurants and other businesses across the city in their search for 74 sailors who had absconded from the Empress of Scotland.[14]

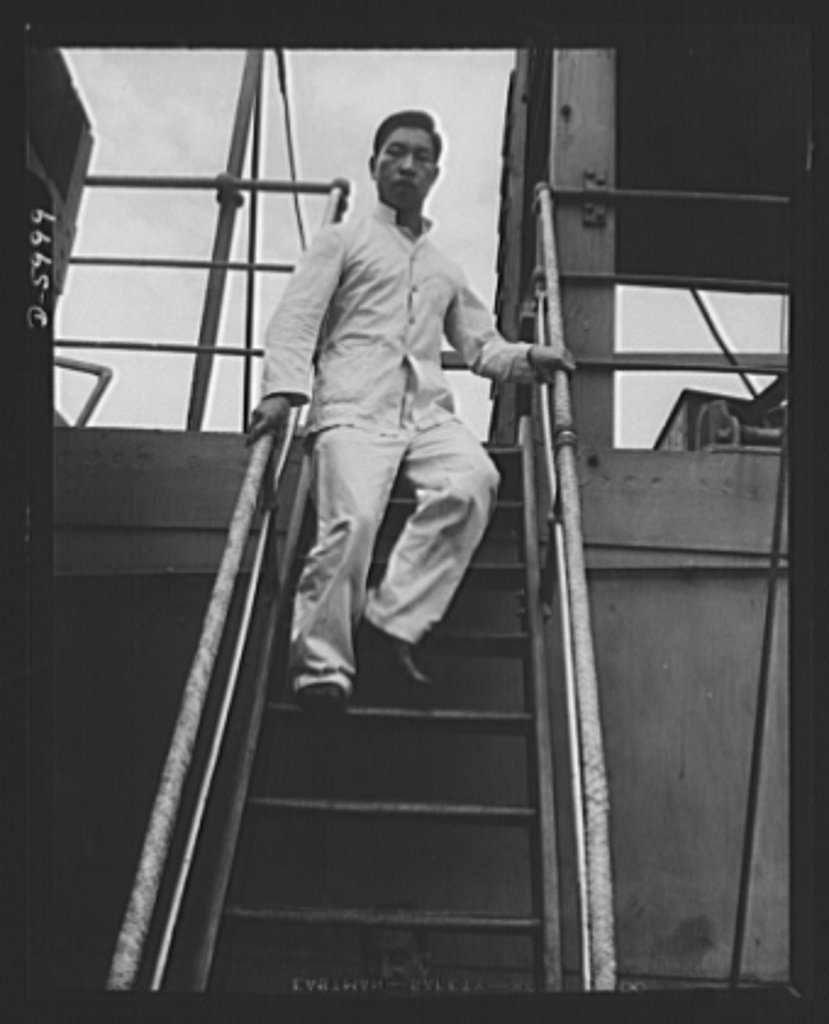

Downplaying officials’ zealous enforcement practices, the U.S. Office of War Information sought to parlay the British government’s decision to permit shore leave into wartime propaganda showing good will between allies. This coincided with Congress’s passage of the Magnuson Act in 1943, which allotted Chinese immigrants an annual quote of 105 visas, ending outright exclusion. The photographs displayed here portray Chinese sailors seemingly at liberty in New York, without any reference to the long and sometimes violent struggle that these seamen had engaged in to win their rights.

|

|

|

Conclusion

The restrictions that nations like the United States and Britain imposed on Asian sailors’ entry into domestic labor markets prevented these seamen from being able to command higher wages through the free contract of their labor – even though their exclusion was ostensibly based on economic and cultural hazards that their “cheapness” posed. Free trade interests staved off white seamen’s ambitions to exclude Chinese and Asian sailors from employment altogether, since this would be too burdensome to the conduct of business.

It is doubtful that the increasingly strict restrictions that Congress and immigration officials placed on the Chinese and Asian seamen’s freedom of mobility had any real effect on the wages that white American sailors and white immigrant seamen were able to demand. As a spectacle of white supremacy, the harassment of Chinese seamen seeking to take shore leave did serve as a stark and visible public reminder of Asian workers’ place in the global economy, and the lengths that countries like the United States were willing to go to deny liberty of contract to certain classes of racialized labor – under the auspices that they were threats to become illegal immigrants.

Today, the dominance of container ships in global shipping has led to the further automation of maritime labor and reduced the number of seamen transporting goods around the world. Goods still enjoy a freedom of mobility – customs inspections and tariffs notwithstanding – that crewmembers on those vessels lack. In the United States, the State Department requires all sailors (and flight crews) arriving in the United States to have crewmember visas if they are to enter the United States on a temporary basis, which are only good for 29 days.

In recent years, there have been numerous incidents where officials have discovered crews working in conditions that commentators have described as tantamount to modern-day slavery. Sailors have reported being denied potable water and food, wages they were promised, and the right to go ashore. Rarely do writers on this topic acknowledge how immigration policies enable exploitation, by denying foreign shipping crews the right to enter and participate in labor markets where they might escape an employer attempting to keep them captive on ship. Immigration restrictions have become so commonplace and accepted that the free mobility aspect of free labor rarely gets mentioned at all.

The author would like to thank Janet Urban for her work editing and formatting the images that appear here.

Notes

- In re Ah Kee, 21 Federal Reporter 520.

- Hager to Daniel Manning, Secretary of Treasury, July 26, 1886, Custom Case Files no. 3358d, NARA, DC, Box 9, Folder 3.

- William Wallace Bates, American Marine: The Shipping Question in History and Politics (Boston: The Houghton Mifflin Co., 1893), 267; 356-7.

- Furuseth, “The Campaign Against the La Follette Bill,” Survey, July 31, 1915, 399.

- By 1910, Rule 22 pertained to the governance of seamen’s landing. U.S. Department of Commerce and Labor, Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization, Immigration Laws and Regulations of July 1, 1907, Eleventh Edition, December 12, 1910 (Washington: G.P.O., 1910), 43-7. The history of how immigration officials governed the entry of Chinese sailors at different points in time can be found in a detailed internal research paper that attorneys working for the Bureau drafted while preparing to appeal the decision in U.S. v. Jamieson (1911), 185 Fed. 165. In Jamieson, Judge Learned Hand of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York questioned whether immigration officials had the authority to hold shipmasters legally and financially responsible in cases where they had no reason to suspect Chinese seamen granted shore leave were planning to desert, and whether the bonding of seamen was a power that Congress had formally extended to immigration officials. The appeal was eventually withdrawn due to a technicality. A. Warner Parker, “Memorandum to the Attorney General,” March 3, 1911, File 52157/9, Subject Correspondence Files, NARA, DC.

- 1917 Immigration Act (An Act to Regulate the Immigration of Aliens to, and the Residence of Aliens in, the United States), 39 Stat. 874, sec. 31.

- Arshowe Family, 1900 U.S. census, Manhattan, New York, New York, roll 1080, page 10B, enumeration district 0017, FHL microfilm 1241080; digital image, Ancestry.com, accessed September 21, 2014. According to the 1900 census, the couple had been married since 1888 and had three children, although only one son, Charles Vincent, was still living. H.R. Sisson, Chinese Inspector, to F.W. Berkshire, Officer in Charge, November 7, 1903; Frank Sargent, Commissioner-General of Immigration, to Berkshire, April 25, 1904, File 34/182, Box 230, Chinese Exclusion Acts Case Files, NARA, NY.

- The memorial was entered into the Congressional Record in 1913. 50 Cong. Rec. 5672 (1913). On the politics and aim of the 1915 Seaman’s Act, see Fink, Sweatshops at Sea, and Jackson, “‘The Right Kind of Men.’”

- Cited in Fink, Sweatshops at Sea, 107.

- Tabili, “The Construction of Racial Difference in Twentieth-Century Britain: The Special Restriction (Coloured Alien Seamen) Order, 1925,” Journal of British Studies 33, no. 1 (1994): 66.

- Palmer, Immigration Inspector, to Immigration Service, Galveston, Texas, August 18, 1913, File 52516/5A, Subject Correspondence Files, NARA, DC.

- Pegler-Gordon, “Shanghaied on the Streets of Hoboken,” 232-4.

- “Hoboken Takes a Joke,” The Nation, Aug. 3, 1927. See also Pegler-Gordon’s discussion in “Shanghaied on the Streets of Hoboken.”

- Lee, “Hunting for Sailors.”

Archives and Works Consulted

Archives

Custom Case Files no. 3358d, 1877–1891, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC, Record Group 85 (Custom Case Files no. 3358d, NARA, DC).

Subject Correspondence Files of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC, Record Group 85 (Subject Correspondence Files, NARA, DC).

Chinese Exclusion Acts Case Files, 1880–1960, Immigration and Naturalization Service, Record Group 85, National Archives and Records Administration–Northeast Region (Chinese Exclusion Acts Case Files, NARA, NY).

Works Consulted

Auerbach, Jerold. “Progressives at Sea: The La Follette Act of 1915.” Labor History 2 (1961): 344-60.

Auerbach, Sascha. Race, Law, and “The Chinese Puzzle” in Imperial Britain. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

Balachandran, G. “Making Coolies, (Un)making Workers: ‘Globalizing’ Labour in the Late-19th and Early-20th Centuries.” Journal of Historical Sociology 24, no. 3 (2011): 266-96.

Barde, Robert Eric. Immigration at the Golden Gate: Passenger Ships, Exclusion, and Angel Island. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, 2008.

Becker, Bert. “Coastal Shipping in East Asia in the Late Nineteenth Century.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch 50 (2010): 245-302.

Chang, Kornel. Pacific Connections: The Making of the U.S.-Canadian Borderlands. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012.

Fink, Leon. Sweatshops at Sea: Merchant Seamen in the World’s First Globalized Industry, from 1812 to the Present. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

Frost, Lionel. “The Economic History of the Pacific,” in The Cambridge World History, Part IV – World Regions. Edited by J.R. McNeill and Kenneth Pomerantz. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Hsu, Madeline. Dreaming of Gold, Dreaming of Home: Transnationalism and Migration Between the United States and South China, 1882–1943. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2000.

Hyslop, Jonathan. “Steamship Empire Asian, African and British Sailors in the Merchant Marine c.1880–1945.” Journal of Asian and African Studies 44, no. 1 (2009): 49-67.

Jacks, David S., and Krishna Pendakur. “Global Trade and the Maritime Transport Revolution,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 14139, June 2008, http://www.nber.org/papers/w14139.pdf.

Jackson, Justin. “‘The Right Kind of Men’: Flexible Capacity, Chinese Exclusion, and the Imperial Politics of Maritime Labor Reform in the United States, 1898–1905.” Labor 10, no. 4 (2013): 39–60.

Lee, Erika. At America’s Gates: Chinese Immigration During the Exclusion Era, 1882–1943. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

Lee, Heather. “Hunting for Sailors: Restaurant Raids and Conscription of Laborers during World War II,” in A Nation of Immigrants Reconsidered: US Society in an Age of Restriction, 1924-1965. Edited by Maddalena Marinari and Madeline Hsu. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2018.

Levinson, Marc. The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006.

McKeown, Adam. “Ritualization of Regulation: The Enforcement of Chinese Exclusion in the United States and China.” American Historical Review 108, no. 2 (April 2003): 377–403.

Moya, Jose C., and Adam McKeown. “World Migration in the Long Twentieth Century,” in Essays on Twentieth-Century History. Edited by Michael Adas. Philadelphia, Temple University Press, 2010).

Ngai, Mae. The Lucky Ones: One Family and the Extraordinary Invention of Chinese America. New York: Haughton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010.

Oyen, Meredith Leigh. “Fighting for Equality: Chinese Seamen in the Battle of the Atlantic, 1939-1945.” Diplomatic History 38, no. 3 (2014): 532–33.

Pegler-Gordon, Anna. “Shanghaied on the Streets of Hoboken: Chinese Exclusion and Maritime Regulation at Ellis Island.” Journal for Maritime Research 16, no. 2 (2014): 229-45.

Ransley, Jesse. “Introduction: Asian sailors in the age of empire.” Journal for Maritime Research 16, no. 2 (2014): 117-23.

Tabili, Laura. “The Construction of Racial Difference in Twentieth-Century Britain: The Special Restriction (Coloured Alien Seamen) Order, 1925.” Journal of British Studies 33, no. 1 (1994): 54-98.

Tate, E. Mowbray. Transpacific Steam: The Story of Steam Navigation from the Pacific Coast of North America to the Far East and the Antipodes, 1867-1941. New York: Cornwall Books, 1986.

Urban, Andrew. Brokering Servitude: Migration and the Politics of Domestic Labor During the Long Nineteenth Century. New York: New York University Press, 2018.

Young, Elliott. Alien Nation: Chinese Migration in the Americas from the Coolie Era through World War II. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

Andrew Urban is an Associate Professor of American Studies and History at Rutgers University, New Brunswick. His first book, Brokering Servitude (NYU Press, 2018), examines how federal immigration policies and private entrepreneurs shaped labor markets for domestic service in the nineteenth and early-twentieth century United States, and dictated the contractual conditions under which migration occurred. His current research explores the history of Seabrook Farms, a frozen foods agribusiness and company town in southern New Jersey that recruited and employed incarcerated Japanese Americans, guestworkers from the British West Indies, and European refugees and stateless Japanese Peruvians during the 1940s. @AndyTUrban