“A Tale of Two Cities” in Renaissance Europe, part 2: Valletta and Palmanova’s Utopian Ideals

By C.R. van Tilburg, Universiteit Leiden (The Netherlands)

Dr. van Tilburg is the author of Traffic and Congestion in the Roman Empire (London/New York: Routledge, 2007, repr. 2012). For more information about his work, visit his faculty profile page.

Not all drawings remained merely utopias. I will discuss two examples of cities which were designed as utopias, but were also actually built. They approached the ideal city as constructed according to the concepts of Renaissance planners. They could be constructed as utopias, designed as ideal cities, with perfect civic and military infrastructures. The utopia had to be realised. Nevertheless, putting these designs into practice offered significant challenges.

Valletta

In 1522, the Hospitallers were defeated by the Turks and forced to leave Rhodes; they moved to Malta. On this island, some reinforcements were constructed on a modest scale. There were plans to transform the peninsula, Sciberras, into a heavily strengthened fortress system, but these plans were not realised. In 1565, the famous Siege of Malta took place. After three months, the Hospitallers defeated the Turks. After the victory, the knights decided – taking into consideration Malta’s strategic location – to reconstruct the peninsula and to transform it into a city and strong fortress. Its name was Valletta, in honor of the Commander of the Hospitallers, Grand Master Jean Parisot de la Vallette (1494-1568), who defeated the Turkish army (20,000-48,000 soldiers) with only 8,000 knights.

Initially, the Italian fortress-builder and architect, Francisco de Marchi (1504-1576), proposed to build a fortress with eight bastions, but this could not be realised, as he failed to take into account the height differences on the peninsula. Probably, he was not familiar with the local situation. De la Vallette consulted Pope Pius IV, who sent another architect, Francesco Laparelli to Malta. Laparelli (1521-1570) proposed construction of a new city with one central main street and winding streets in the other parts. His ideas followed Alberti’s. Unfortunately, these ideas were – as far as we know – not drawn or written down, as was the case with Alberti’s.

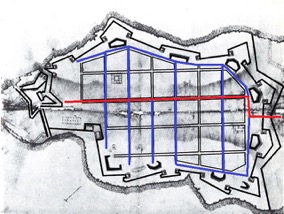

Later on, Laparelli developed a different scheme: a city equipped with bastions, using a Hippodamic street pattern, as some of his contemporaries did. The similarity with the design of another Italian city planner, Pietro Cataneo, is significant: this design involved a remarkable hierarchy between the individual streets and showed various squares. In his second design, Laparelli designed a city without plazas and with larger building-blocks, with four parallel running streets (including the main street) in line with Fortress St Elmo. Significantly, none of these four streets is connected directly to the gate; the main street runs from St Elmo to a bastion (fig. 1). Possibly, Laparelly designed a city where social equality was reflected in the building blocks, in accordance with the humanists’ ideals (and with Hippodamus’ teachings), as described in Thomas More’s Utopia: ‘Everyone had the same amount of wealth, respect, and life experiences. The city where they lived was always geometric in shape, and was surrounded by a wall. These walls provided military strength, but also protected the city by preserving and passing on man’s knowledge’.

Fig. 1. Valletta’s military plan

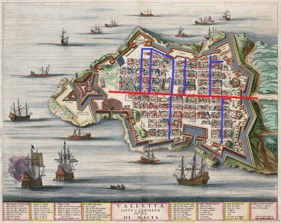

Finally, Laparelli’s fourth design was accepted by the Hospitallers, when the city was already under construction. In this final plan, three lengthwise streets were considerably wider than the others (including the side streets, intersecting the three main streets at right corners); the main street in line with St Elmo, directly connected with the city gate, situated exactly in front of the primary thoroughfare (fig. 2). This last design would doubtless have improved the mobility, creating a better situation than the winding streets (inspired by Alberti) in his previous designs. The peninsular city would be greatly protected by high walls and bastions of stone, following the rocky coastline.

Fig. 2. Valletta’s civic plan, as built

By 1568, Laparelli was disappointed with the project and withdrew as city architect and his successor became his former pupil, Geronimo Cassar. Under his leadership – in collaboration with the Hospitallers – Valletta got its final shape with a division: the ‘collachio’ where the knights were housed, and another part for the other inhabitants. The ‘collachio’ also contained the hospital, the Palace of the Grand Master, the Treasure House, the Chancellery, and the Arsenal, among other structure. In short, De Marchi and Laparelli designed Valletta as a city, according to Alberti’s concept for the ideal city. Nevertheless, this ideal city had to be changed into one with a star or crystal shape, containing a Hippodamic grid within the walls. The Hospitallers forced Laparelli to later his sketches frequently, which had led to his resignation.

In this last design for the city, from a military point of view, Valletta was nearly impossible to conquer. It was situated at the relatively flat level of a high rock, equipped with bastions following the peninsula in a star shape and only one city gate at the land side. The main street to which the gate was connected was a straight one, running directly to Fortress St Elmo, from where the city could be under fire. It seems, however, that the Hippodamic street pattern was initially designed to cope with traffic flow, improve civic infrastructure and provide an esthetic point of view; probably, the Hospitallers disagreed with the military strategy borrowed from Alberti with its narrow, winding streets.

So we see a compromise: on the one hand, inside the important and heavy military infrastructure with strengthened bastions and walls, surrounded by water on three sides and only one city gate on the landward side. On the other hand, a Hippodamic street map, where it would be more comfortable for traffic. As a result of this compromise, Valetta is no ideal city, neither in military, nor in civic respect.

Palmanova

Renaissance city planners sometimes chose a radial map instead of the Hippodamic one. Departing from the center, streets ran to the gates like rays. Other streets encircle the center, running parallel to each other and crossing the radial streets, creating space for building-blocks with the shape of a wedge of cake or a crescent. Cities with a radial map were designed by Filarete, Fra Giocondo, Girolamo Maggi and Francesco di Giorgio Martini. Even more than in case of Hippodamic cities, esthetics plays an important role. Changing a Hippodamic city is quite simple – we have seen that Valletta is not exactly symmetrical due to the geographical situation – but to intervene in a circluar city is nearly impossible. One must build an entirely new wall, or not build one at all. Nevertheless, such cities were really built, and like Valletta, not exactly according to the Utopian, original design intervening in the street system.

Twenty years after the maritime Battle of Lepanto against the Turks (in 1571, six years after the Siege of Malta), the Senate of Venice decided to protect the city on the landward side by means of a city-fortress. The building activities started in 1593, under the leadership of the military engineer Giulio Savorgnano (already 78 years old, assisted by the younger Florentine Bonaiuto Lorini). Like Valletta, this city was designed as a utopia, according to Renaissance-humanistic ideals, military as well as civic. At the drawing table, and seen from above, the city looked like a crystal: a hexagonal place in the center, encircled by three concentric streets with nine corners, corresponding to the nine bastions at the nine corners of the city wall (later, in the 17th century, the fortress was enlarged with ravelins). Nevertheless, the final result was not the original design by Savorgnano and Lorini. Initially, the gates were situated close to the bastions, so that they were better protected. In a later stage, they were moved to the center of the ‘curtains’ (the stretches of the walls between two bastions).

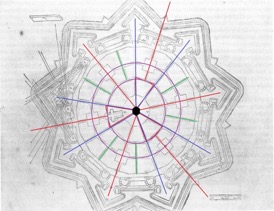

A far larger operation was the extension of the approach roads to the central square. In 1596, Lorini wrote his book Delle Fortificazioni, in which he designed a radial city that had striking similarities with Palmanova that one had to conclude that this was a first design of it. In this plan, the military problems of Palmanova were strongly reduced. Apart from the situation that there were two concentric streets instead of the three realised in Palmanova, the most striking difference was that the streets connected to the gates were not running directly to the central place, but ended against a building block. Inevitably, this made traffic to follow a zigzag route. As in Palmanova, as it was actually built, there were nine radial streets; three of them run from the gates to the inner concentric street and the other six from the central (hexagonal) place to the six bastions in the city wall. Furthermore, there were nine more streets connecting the inner and outer concentric streets, totaling 18 radial streets (fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Palmanova’s military plan

From a military point of view, such a design would be very effective: invading enemies – after passing through the gates – would not be able to go straight on to the central place, but would be forced to make a zigzag route. Such a situation would make it more difficult to take under fire the center of the city and to keep it under control. In the same way, the change of position for the gates made them less safe. The design was modified. As in the case of Valletta, this was probably due to a change in opinion of the authority supervising the plans – in this case the Senate of Venice. In 1593, Marcantonio Barbaro was appointed ‘Proveditore Generale’ of the fortifications; he gave permission to change the original design by Savorgnano and Lorini, involving (amongst other alterations) the extension of the access roads straight to the central place (fig. 4), causing a decrease in the city defense.

Fig. 4. Palmanova’s civic plan, as built

Like in Valletta, we see here a shift from military to civic interests. The street system was modified to the wishes of the inhabitants, improving traffic, whilst the strategic/military interests were considered as less important. A direct connection between the gate and the central square increased ease of mobility for citizens.

From a military point of view, here again, the ideal city could not be realised. Was Palmanova, then, an ideal city from a civic point of view? No, it wasn’t. As the American scholar Edward Wallace Muir Jr. described the sad fate of Palmanova:

“The humanist theorists of the ideal city designed numerous planned cities that look intriguing on paper but were not especially successful as livable spaces. Along the northeastern frontier of their mainland empire, the Venetians began to build in 1593 the best example of a Renaissance planned town: Palmanova, a fortress city designed to defend against attacks from the Ottomans in Bosnia. Built ex nihilo according to humanist and military specifications, Palmanova was supposed to be inhabited by self-sustaining merchants, craftsmen, and farmers. However, despite the pristine conditions and elegant layout of the new city, no one chose to move there, and by 1622 Venice was forced to pardon criminals and offer them free building lots and materials if they would agree to settle the town.”

Summary and conclusion

Long before Thomas More, people developed notions about the ideal city. Plato described the ideal city, Atlantis, although he only knew it by means of legends. Hippodamus and Aristotle described ideal street maps: respectively, a grid-pattern map, and a more chaotic map (supposedly for better defense). Vitruvius, the first author whose work came to us in complete form preferred a Hippodamic city, equipped with strong walls.

In the Italian Renaissance, new ideas about ideal cities arose. Many scholars, humanists, philosophers, artisans, engineers and architects designed their ideal cities by means of models and sketches. The first one of them, launching new ideas, was Leon Battista Alberti, who – following Vitruvius – wrote a work on city planning and architecture. On the subject of street maps, he did not agree with Vitruvius: Alberti preferred gently winding main streets, and a labyrinth of narrower alleys to accommodate a military point of view.

Influenced by new social ideas and the failings of medieval cities, a new generation of humanist city planners arose. They designed new cities, using models or on paper, with a geometric and symmetric map, with equal building blocks, star- and crystal-shaped, equipped with city walls and bastions. Such a city was Sforzinda, designed by Filarete, the first design of a city in early modern times.

To realise cities, designed in such a way, they could turn to the plans of the earlier generation of Italian military architects and engineers, like De Marchi, Laparelli, Savorgnano and Lorini. Both Valletta and Palmanova were, initially, designed with a focus on military concerns: narrow streets, a zigzag between the gate and the centre, resulting – inevitably – in a reduced possibility to cope with traffic flow. The supervisors (the Hospitallers and the Senate of Venice), however, gave priority to civic interests over military concerns, thus producing a wider and more direct infrastructure. The compromise that resulted was a long way away from a perfect, ideal city; either from a military, or from a civic point of view.

Palmanova ended as a city where hardly anybody wanted to live. A crystal-shaped place, beautiful to see on the drawing-board, but ultimately, in terms of lived experience, it remained a utopia.