“A Tale of Two Cities” in Renaissance Europe, part 1: Antiquity’s Influence on Balancing Civic and Military Infrastructures

By C.R. van Tilburg, Universiteit Leiden (The Netherlands)

Dr. van Tilburg is the author of Traffic and Congestion in the Roman Empire (London/New York: Routledge, 2007, repr. 2012). For more information about his work, visit his faculty profile page.

In our time, modern cities are planned and developed without paying any thought to the possibility of sieges. From 1800 onwards, no city would be able to resist modern weapons in any case. Cities built before that time, however, had to offer military capabilities, in order to protect their inhabitants in times of struggle or war. Each city was a compromise: there were, on the one hand, civic interests that would profit from a wide infrastructure, but, on the other hand, martial interests, for which a narrow infrastructure would be preferable. People who planned the ideal city had to find a balance between these two functions. The most famous city planner of Antiquity was the Roman architect Vitruvius, who designed the ideal city, with a grid street pattern and effective city walls.

In the 15th century, the period of the Italian Renaissance, Vitruvius’ work was copied and studied profoundly. The scholar Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472) wrote a work about city planning, following Vitruvius; he thus inspired a whole generation of researchers who engaged into city planning. In some cities, an ideal compromise – a utopia – of civic and military infrastructure seemed to be realized. During the planning and building process, however, conflicting interests diminished their ideal shape.

Vitruvius and his predecessors

The first individual – as far as we know – who was engaged in developing this ideal city was Hippodamus of Milete. He designed and developed his typical street grid pattern (streets crossing each other in a right corner). Hippodamus was an adherent of democracy: equality between people, equal streets, equal parcels. His most famous project was the reshaping of the Piraeus, the harbour of democratic Athens (± 450 BC). The fourth century philosopher Aristotle, on the other hand, an opponent of democracy, refers in his Politics to the advantages of an irregular, winding street pattern, which makes it difficult for enemies to conquer the city; they can get lost and finally lose the attack.

The Roman architect and engineer Vitruvius Pollio (85-20 BC) is the first city planner whose work has survived to our days: De architectura libri decem, ‘On Architecture in ten books’. His ideal city was Hippodamic, as seen in Roman cities like Colonia Augusta Treverorum (Trier) and Colonia Agrippina (Cologne) and, in England, Camulodunum (Colchester) and Lindum (Lincoln). The civic infrastructure consists of a grid street pattern with a central square (forum). The military infrastructure in these cities is restricted to a well-functioning wall with gates, towers and ditches. Conquering such a city was difficult at that time; the main weapons were shields, swords, spears, battering rams and catapults. Solid walls with towers could resist them. Only gates were vulnerable; most of the cities that were conquered were invaded by the gates.

To make the advance toward a gate even more difficult, Vitruvius introduced the so-called ‘Vitruvian bend’. In front of the gate, the access road had to be planned in such a way that the enemy was forced to approach the city with the right side of his body turned to the city wall. Soldiers were usually right-handed, so they would be carrying their shields on the left arms, so that their right-hand sides were relatively unprotected. Thus, they were an easy target for city defenders standing on the wall (Vitr. 1.5.2). Whether the ‘Vitruvian bend’ was actually applied is doubtful, however. In front of two gates of Forum Hadriani (a Roman city in the neighbourhood of The Hague), indeed, curves are discovered, but it is not sure whether they were designed with a military objective. The curves are short and gentle, and enemies would be forced to turn the right sides of their bodies towards the city wall only for a while.

Alberti

During the Middle Ages, Vitruvius’ writings were still known, but there was little need to bring his teachings into practice. Already in late Antiquity, a (partial or total) depopulation of cities took place. During the Middle Ages, some Roman cities survived; other cities arose spontaneously. These cities, however, were usually small, so that a simple civic infrastructure was sufficient. Since they were relatively independent, they still had to be equipped with a sufficient military infrastructure.

At the end of the Middle Ages, new ideas concerning city planning arose; ancient Roman theories on this theme inspired scholars to research them. Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472) was an Italian painter, poet, scholar, philosopher, musician and architect. As an architect, he got his inspiration from Vitruvius and he wrote De re aedificatoria libri decem, ‘On the art of building in ten books’. In this work, he pays more attention to urbanistic aspects than Vitruvius, such as the construction of roads and sewage systems. The essential difference, in short, between Alberti and Vitruvius was therefore that Vitruvius tells how buildings were built, while Alberti, on the other hand, prescribes how buildings were to be built.

Following Vitruvius, Alberti recommends city walls with towers, which force the enemy to turn his unprotected side towards the city wall (Alberti IV.4). Concerning the ‘Vitruvian bend’, Alberti states as follows: ‘The entrance will be safer if the road does not lead directly to the gate, but runs to the right or left along the wall, and preferably even directly under the battlements’ (Alberti IV.5). Probably, this difference of perspective can be explained by the fact that shields, bows and arrows were outdated weapons by then: the gun, blunderbuss, and other firearms covered a greater range and had gunpowder that exceeded the force of ancient Roman artillery. The protection of city walls would not always be sufficient to resist these new types of armaments. In fact, during Alberti’s lifetime, in 1453, Constantinople was conquered by means of guns. During the course of the sixteenth century, stone walls began to be replaced by earthen ones to better resist cannon and gun attacks.

Alberti’s military ideas may be derived from his street patterns as well. He appears to be an adherent of Aristotle’s map with winding streets, rather than Hippodamus’ and Vitruvius’ grid map. It may be relevant that in 15th century Italy the cities were independent – like in Aristotle’s Greece – but in Vitruvius’ Roman Empire, they were not. Thoroughfares approaching and passing the gates were called viae militares (military roads). To prevent highwayman raids, they had to be constructed at a higher level and to be free of bushes, to give travellers a better overview. Inside a city, such a military road could not run straight: it should be gently curved, to suggest that the city was larger than it actually was, and of more importance, to offer panoramic views showing façades of different buildings (Alberti IV.5).

Inside the city, Alberti distinguished – besides the viae militares – also viae non militares (nonmilitary roads). These were side streets, connecting the main avenues, and also interconnected in various ways across themselves. They were winding, apart from the side streets, following the course of the city walls. In the ideal situation, these winding streets formed a labyrinth; enemies invading the city could get lost and the invasion rendered unsuccessful (Alberti IV.5). This happened in Antwerp in 1583, called the ‘French Fury’. The Duke of Anjou was planning to conquer the city while a weapons show was going on, but the plan leaked out. Instead, the main street was closed and the invaders were forced to enter the labyrinth of winding streets. The citizens who were living there killed 1,500 French soldiers, who were dragged out of the city through the Kipdorp Gate. In contrast, the city of Antwerp lost only 80 people.

The Utopians

Vitruvius’ and Alberti’s teachings evoked entirely new insights concerning city planning. Citizens were confronted with problems of the medieval city: a usually chaotic street pattern, rubbish-dump, epidemics, stench and social inequality. Not only theology and humanism, but also city planning became a point of discussion. Italy, the cradle of Renaissance, was also the cradle of new ideas on city planning, especially ideas about the ideal city. A city with a clear street system; a clean city, a social city, a happy city and, moreover, a symmetric city. A city as a piece of art: a utopia.

Renaissance ideal cities reveal a few of the fundamental strengths — and also some of the shortcomings — of planning diagrams. First, they are every place and no place, clearly representing urban space in plain view, but with no geographical references, and therefore none of the context or constraint that comes with building actual cities. Second, they contribute to a broader discourse about societal ideals and how they might be manifested in the good city. Finally, they provide a template repeatedly expressed, modified and reproduced both on paper and on the ground. (End of quotation.)

One of the first Renaissance designers was Antonio di Pietro Averlino, known as Filarete (1400-1469), a contemporary of Alberti. Filarete differs from Alberti in the same way as Alberti differed from Vitruvius. Alberti preferred models (so, unfortunately, we have no design sketches or drawings of his ideal city); Filarete, however, preferred construction drawings. In 1465, he wrote Trattato di archittettura, designing – as the first Renaissance-humanist – an entirely new city, called Sforzinda, after Francisco I Sforza, Duke of Milan, his principal benefactor. For the first time, a design of an ideal city had been drawn.

The design of this city – that was never built – consisted of two rotated squares, making an octagonal star shape. Sforzinda can be considered as a reaction to organically-grown medieval cities, which were difficult to conquer, but also difficult to control in times of turmoil. Filarete designed eight watchtowers on eight corners. Another tower was planned in the central place of the city. Around the walls a circular canal was planned. Possibly, this canal was inspired by the design of Atlantis. According to the legends, Atlantis, the famous ideal city described by Plato, was encircled by such canals. The star shape, including a central point, was also a symbol of the power of the monarch, the tyrant. This model – a center, from which streets were running to the star-shaped city wall and city gates – was adapted by all later city planners, who had greater military expertise. The most important Italian Utopians mentioned here are, besides Filarete, Fra Giocondo (1433-1515), Francesco di Giorgio Martini (1439-1502), Pietro Cataneo (± 1510-1570), Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574), Daniele Barbaro (1513-1570), Girolamo Maggi (1523-1572) and Antonio Lupicini (1530-1607).

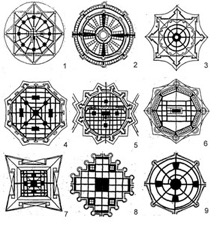

It is remarkable that, in the first instance, radial cities were designed. In a later time, we find Hippodamic street-grid patterns within the star- or crystal-shaped city walls. In this respect, Girolamo Maggi was an exception, because he planed a radial city in a later time (fig. 1). See the sketches below.

Fig. 1. Italian Utopian Renaissance city maps. 1. Filarete (1400-1469), 2. Fra Giocondo (1433-1515), 3. Girolamo Maggi (1523-1572), 4. Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574), 5. Antonio Lupicini (1530-1607), 6. Daniele Barbaro (1513-1570), 7. Pietro Cataneo (± 1510-1570), 8 and 9 Francesco di Giorgio Martini (1439-1502).

In principle, cities as those described above could be built in reality. These sketches, however, did not take into account natural phenomena, such as rivers, lakes, height differences, harbours etc. In many ways, these drawings remain utopias…

Next Monday, check back for the second and final installment of Dr. van Tilburg’s work on city infrastructures, defensive features and urban mobility during Antiquity and the Renaissance in Europe.